The Pardon Nobody Heard

For nearly twenty years after the state spared his neck, Buddy Green lived out his sentence behind concrete walls and steel bars — out of sight, out of mind, except for the two boys who carried him like a ghost locked in their chests.

Almost nothing survives from Buddy’s prison years. A catastrophic fire in Norfolk in the early ’60s destroyed stacks of public and legal records. Buddy left no diary. No remorseful memoir. No tallies of fights won or friendships made. We’re left with a man-sized blank — except for the letters.

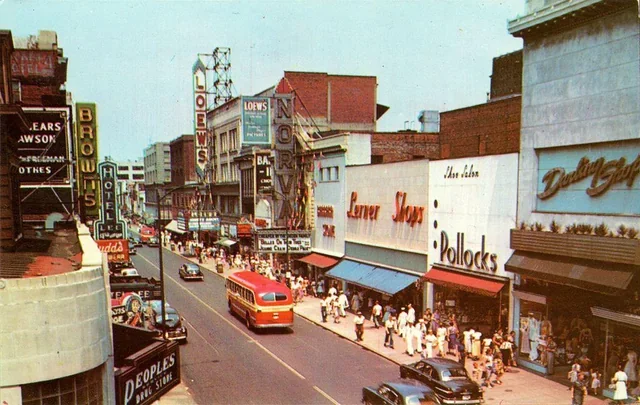

Granby Street, Norfolk, 1973 — the world Buddy Green stepped back into after his conditional pardon, bright and bustling and utterly changed from the city Bill Allman once served.

Somewhere in that long corridor of years, someone — a guard, a cellmate, a chaplain — must have mentioned who the Allman Brothers were.

And Buddy would’ve had to sit there with the knowledge that those two long-haired stars — Duane and Gregg — were the sons of the man he’d killed for four dollars and a borrowed car.

So, still behind bars, still serving a life sentence, Buddy did the one thing the courts couldn’t order him to do or not to do: he reached out.

The letters began arriving for Gregg, written on prison stationery and carrying the desperation of a man trying to smuggle his humanity out through the mail slot.

“I’m so sorry,” he wrote. “I’m sorry to the sixteenth degree.”

Over and over — the looping apologies of a man begging a boy to rewrite the past for him.

Gregg read some of them. Remarkably, he opened the envelopes. He let the poison in. But he never wrote back. Never granted Buddy the one thing he craved: acknowledgment.

“I think I might’ve done away with the letters,” Gregg admitted decades later, in My Cross to Bear.

To answer Buddy would’ve meant pulling the lid off everything Gregg had spent a life tamping down: that the man who murdered his father may have been sorry, or sick, or simply broken.

For the Allman boys, the silence was the point. They didn’t lose a father so much as inherited an absence, a black hole where something strong and good was supposed to be.

Buddy had taken their father. The boys refused to give him anything back — not even a word.

1973: The Gate Opens

When freedom finally came for Buddy Green, it came disguised in bureaucratic prose, a single line in the Virginia governor’s annual report:

“In view of the length of time served with a good institutional adjustment, favorable recommendation from the Director of Corrections, and after a trial on work-release, which trial has been satisfactory, subject is granted a conditional pardon…”

No mention of Bill Allman, the father lost. No mention of the shattered young family left behind. No mention of two Southern boys carrying the wound like a birthmark, building a mountain of grief on top of the grave Buddy dug for them.

Just tidy civil-service language: good adjustment, favorable report, satisfactory trial.

The signature at the bottom belonged to Governor Abner Linwood Holton Jr., the Navy veteran and Republican reformer who desegregated Virginia’s schools and sent his own children into Black classrooms to prove his point. A just man in many ways — but also a man presiding over a system that bent easily for an older white veteran while seven young Black men, the Martinsville Seven, had been executed two decades earlier for a crime that didn’t take a life.

Buddy walked out of prison in 1973 with a clean slate and the governor’s blessing.

Most people didn’t even know Buddy received a pardon. Gregg must not have known. In interviews and in his own memoir, he said the man who killed his father had died in prison. Coming from Gregg, everyone believed it. Even reporters.

But Buddy didn’t die behind bars.

He walked free.

And by the time he stepped out into the sunlight, Duane Allman was dead. Gregg was drowning in grief, fame, guilt, and heroin. And the two little boys Buddy had orphaned were kings of a kingdom built from sorrow.

The letters were gone, trashed by the boy Buddy had wounded. But the words surely stayed — you could hear them in the rasp of Gregg’s voice, in the sigh of the Hammond B-3, in the spaces between the notes — spaces so wide you could hear a father’s last breath echoing forever. And then a brother’s last breath echoing forever.

If you want to know what those letters said, don’t look for the pages. You’ll find the words in “Whipping Post,” in “Dreams,” in “Not My Cross to Bear.” Gregg didn’t forgive. He sang. And that silence — the choice to answer with music instead of mercy — says more about the burden of grief than any letter Gregg could have written in response to Buddy’s expressions of regret.

And then Buddy vanished again, into a small life by the sea, back to East Ocean View — where he had murdered Bill Allman — to wait for his final curtain, which didn’t fall until he was 100 years old… in 2024.

Buddy Green finally died long after Duane Allman was gone, seven years after Gregg died, and decades after their songs had become myths.

But the wound? Still there.

Passed down to the next generation (and maybe the next).

Buddy’s prison door had swung wide open but the Allmans’ never did.