The Hidden Legacy of Marie Stephens: A Windrush Girl in Middle Georgia

Sometimes the most remarkable stories are the ones we pass in the hallway without even knowing it. Marie Stephens-Thomas is one of those stories — a woman who quietly carries the spirit of the Windrush generation, the music of her Jamaican roots, and the power of a family legacy that helped shape Liverpool’s post-war sound.

Here in Middle Georgia, she tends to elders in a memory care ward, all while holding a thread that ties her and our region to Liverpool, Jamaica, Africa — and back again.

Before reggae took root in Jamaica and before the Windrush ships brought new music to Britain, there were men like Roy Stephens — Marie’s father — who learned to play wooden instruments carved by his father’s hands in Kingston, Jamaica. Today, Marie brings that history to Middle Georgia where she tends her family stories and cheers on her favorite Macon reggae band.

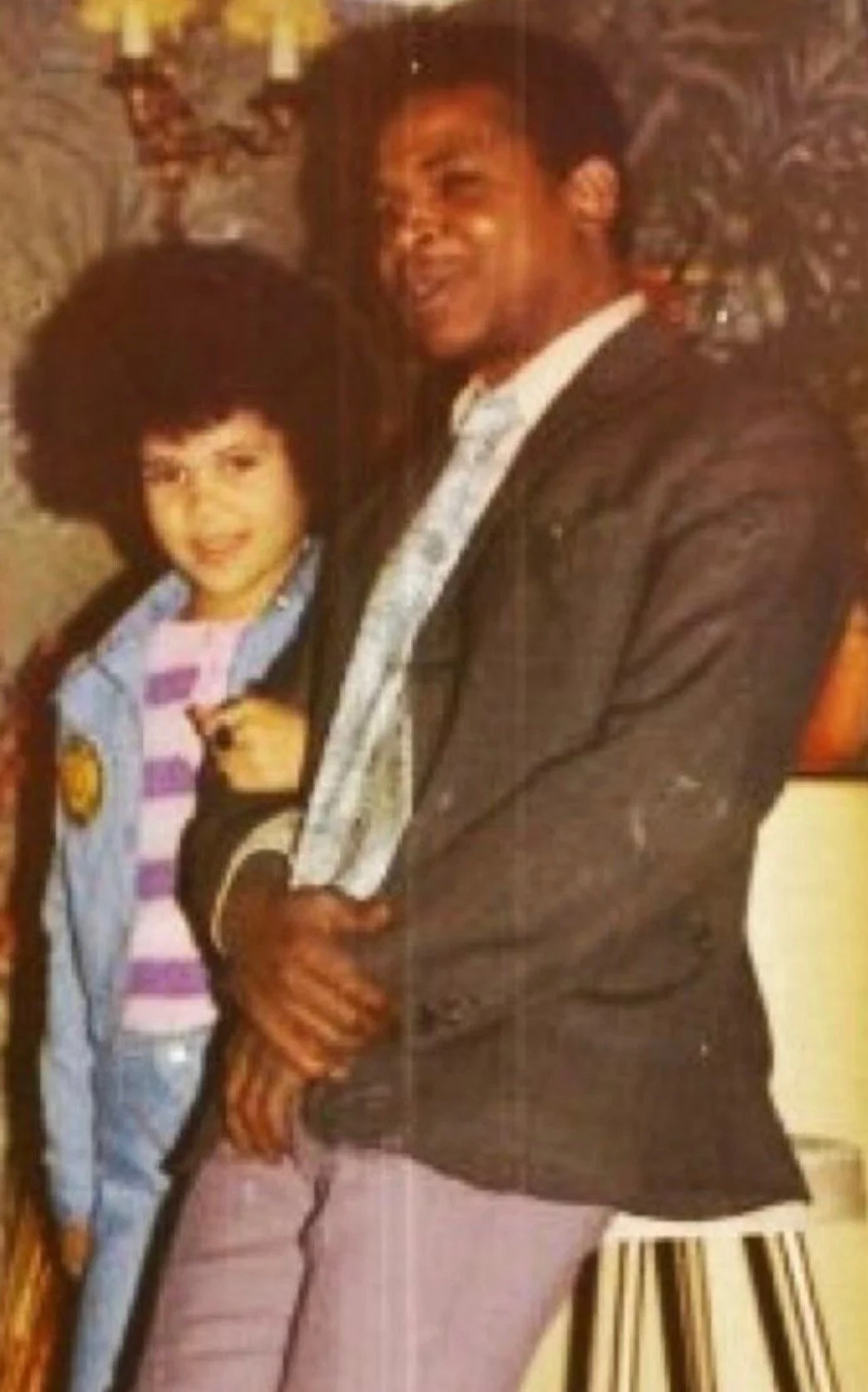

Marie Stephens Thomas centered between her parents, the two people who gave her both roots and rhythm: Kathleen “Babs” (née Arshet) and Roy Stephens.

The Windrush Generation: Named for the HMT Empire Windrush

When you see Marie at work in a memory care ward — guiding elders, laughing gently at their stories, moving with the ease of someone who serves with her whole heart — you’d never guess her roots run all the way from Kingston to Liverpool — and into the heart of Middle Georgia.

Back home in England and Japan — people treat Marie with near-reverence, wanting to talk with her and hear her stories. But here, she blends in, bringing an extraordinary family legacy quietly into ordinary rooms.

Marie was born in Liverpool in 1963, to a Jamaican father and an English/Malaysian mother, Kathleen (Babs), who met as teenagers in postwar England. Her father, Roy Stephens, was just 18 when he left Jamaica in 1948, one of six brothers — out of eight — who made the journey to Britain to help rebuild the country after World War II.

They were called the Windrush Generation — named for the HMT Empire Windrush that brought the first wave to Liverpool in June of that year.

When the HMT Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in June 1948, it carried more than 800 passengers from the Caribbean — among them RAF veterans, tradesmen, artists, and families seeking opportunity in the “Mother Country.” Britain needed their labor but rarely offered welcome. Around this same time, Roy Stephens and his brothers made their own journeys from Jamaica to England, part of the same wave of hope and hardship that came to be known as the Windrush generation — a movement that reshaped British life and culture for generations to come.

Roy and his brothers, all taught music in Kingston by their father on handmade wooden instruments, carried more than strong backs and willing hands. They brought the heartbeat of African rhythm, the sway of island reggae, the improvisation of jazz. And they needed music and ability to improvise — because the new life they stepped into was lined with closed doors.

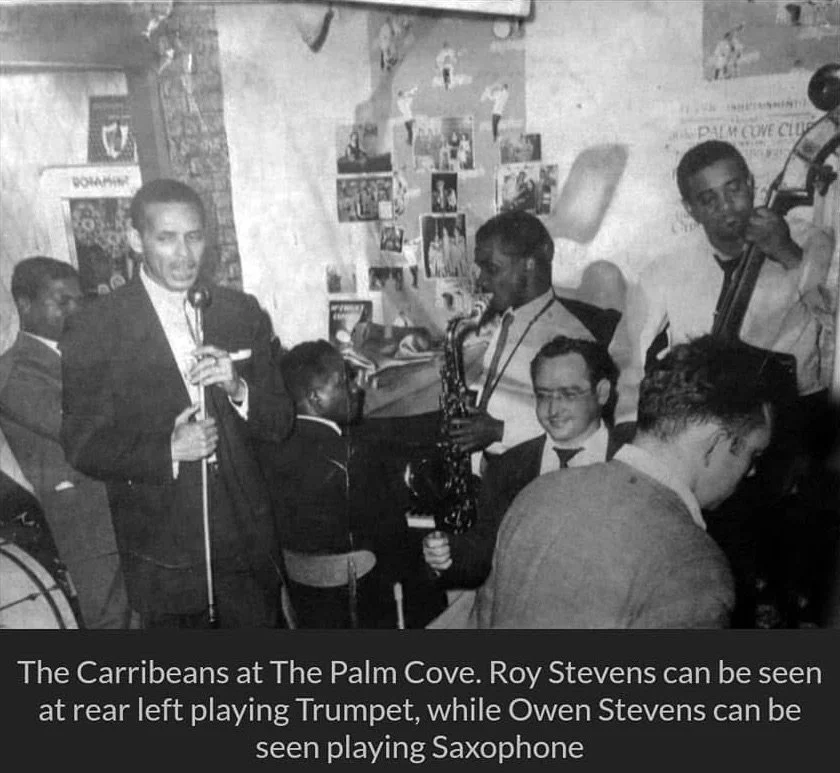

Denied housing because of their color, they bought their own place and bunked together. Banned from whites-only clubs, they built their own: The Palm Cove, The Embassy Hotel with its nightclub, the 101, places that gave other musicians their chance to practice on a real stage.

When the local scene said no, the Stephens brothers said yes — yes to music, yes to community, yes to carving out their own place. Roy was a trumpeter, drummer, and piano player; he and his brothers formed a band that made its rounds across Liverpool’s dance halls, bringing that Afro-Caribbean spark and modern jazz to a country finding its postwar sound.

With all they contributed, the Stephens brothers were the architects of Liverpool 8’s mid-century music scene.

Marie keeps Roy’s story alive for her own children and grandchild. She has books and photographs — a black-and-white of her father and mother at 19, a young Jamaican man and his white English bride, both smiling like they know the path ahead will be rocky but worth it. Each year, new branches of that story reach toward Marie — newly found brothers, cousins, and friends who help her trace the melodies of her paternal lineage.

Roy and Babs Stephens, nineteen and unafraid — the beginning of a generation-spanning duet between islands and continents.

Wedding portrait, St. Peter’s Church, Liverpool, 1949. With Roy’s brother Delroy Stephens and Marie’s cousins, Tina and Melanie.

Marie Stephens Thomas (right) with her cousins, Tina and Melanie — the same girls in the above photo of Roy and Babs’ 1949 wedding. Together, these three embody the fusion of Marie’s family lines: the English-Malaysian heritage on one side and the Jamaican roots on the other.

In England and Jamaica, Marie gets noticed: people want to hear her family’s stories and they want to wrap them all in hugs, from Tokyo to Piccadilly Circus. In June 2023, her father’s face lit up a billboard in Piccadilly Circus — alongside his brothers Delroy, Les, and Owen — a celebration of the Windrush generation. That electronic billboard featuring the Stephens brothers became a national moment of recognition, years before the Windrush scandal finally forced Britain to reckon with the discrimination and injustice it had inflicted on these immigrants for decades.

But here in Middle Georgia? She’s simply Miss Marie, the bright soul who nurses people with dementia and lifts them in body and spirit. She shrugs off the idea that her story matters here.

“I didn’t think anyone would be interested,” she said to me, laughing gently.

But we should be interested. Because when you sit with Marie, you hear how music flows around the world, unstoppable by borders. You see how her grandfather’s devotion to music echoes in the reggae rhythms of Macon’s own Dean Brown, the city’s talented reggae musician/songwriter/producer, and Marie’s friend. You feel how the same drive that built The Embassy nightclub in Liverpool lives on in a woman who supports her favorite local artists, and brings care and dignity to elders here — no stage lights, just everyday grace.

Marie was living in England when her father passed suddenly, and though she was at her mother’s side when she died, that loss came quickly too. She didn’t have the chance to share their later years, a truth that still shapes her work today. “When I look at the residents,” she says, “I see my parents. So I treat them as such.”

Looking at Marie, we see what it means to carry an extraordinary legacy inside an ordinary life: the Windrush spirit, the music-filled family, the smile of Roy Stephens on her face, the spunk of Babs, all passed down in Marie’s eyes.

And so this is her story: Marie Stephens-Thomas, rooted in Middle Georgia for twenty years, carrying the heartbeat of her grandfather’s sought-after piano playing and her father’s Liverpool jazz trumpet into every day. She’s the linchpin — the quiet bridge that connects Africa’s first drum to Jamaica’s reggae to Liverpool’s dancehalls to Macon’s soul streets.

Left Photo: Marie with Mom Babs in Liverpool, circa 1965, outside number 1 Eversley street, the large 3-story family home where Marie and her siblings were raised until the family moved to West Derby, Liverpool, 5 years later.

Right Photo: Marie’s daughter, Jaichelle, born in Japan, 1995, with a portrait of her grandfather Roy Stephens, whom she never met.

The Hidden Legacy of Marie Stephens-Thomas

Some inherit land. Others, a family name. Marie Stephens-Thomas inherited music and migration, and the memory of patriarchs and matriarchs who knew how to keep a family anchored — even while the world shifted beneath them.

Growing up in Liverpool, England, Marie was the baby of the family, raised alongside her older brothers Tony, Derek, and Leroy, who loved every kind of music — reggae, jazz, soul, and funk. Their record player was as much a teacher as any classroom, spinning the rhythms that filled their house and shaped Marie’s earliest sense of joy. Leroy, who shares their father’s love of jazz, still treasures Roy’s trumpet — a family keepsake and symbol of the music that follows the family today.

Liverpool, 1967 — Roy and Babs Stephens with their children Leroy, Derek, Tony, and Marie. The family’s home pulsed with music, from their father’s trumpet to the reggae and soul that would shape their children’s lives.

She was also raised on the stories told by her father and uncles — four of the eight Stephens brothers who left Jamaica in the late 1940s with instruments in hand and ambition in their hearts. Delroy, Les, Owen, and Roy were men on the move: musicians, innovators, and cultural trailblazers. They formed the core of Delroy Stephens & The Commandos, a 17-piece Jamaican orchestra that took their calypso-jazz sound to England just as the Windrush generation began reshaping British identity.

Marie’s father Roy served in the Royal Air Force, playing in the RAF band before joining his brothers to build something that had never existed in postwar Liverpool: a string of vibrant, Black-owned nightclub-restaurants where diasporic rhythms mingled with old musical standards and contemporary tunes in English nightlife.

The Palm Cove, The Beaufort Grove, and the 101 were more than venues — they were havens. You might hear Owen on saxophone and double bass, Roy on trumpet, Les on trumpet, bass and wind instruments, and Delroy on piano, emceeing between sets. These were spaces where West Indians gathered to eat, dance, and exhale — safe from the sting of “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” signs that still hung outside British lodging houses. In time, Les, Roy, and Ken each opened clubs of their own, bold acts that turned ownership into freedom.

They were also deeply political spaces. Roy Stephens, founder and president of the Jamaican Merseyside Association, didn’t just play horn — he blew open conversations about housing discrimination and Black entrepreneurship, even launching Jamaica Investments, Ltd., to help Black British residents secure mortgages when banks wouldn’t lend to them.

But visionaries must be grounded somewhere. And for the Stephens brothers, that grounding started at 22 Charles Street in Kingston, Jamaica — home of Marie and Rudolph Stephens, who raised 12 children with discipline, wisdom, and love.

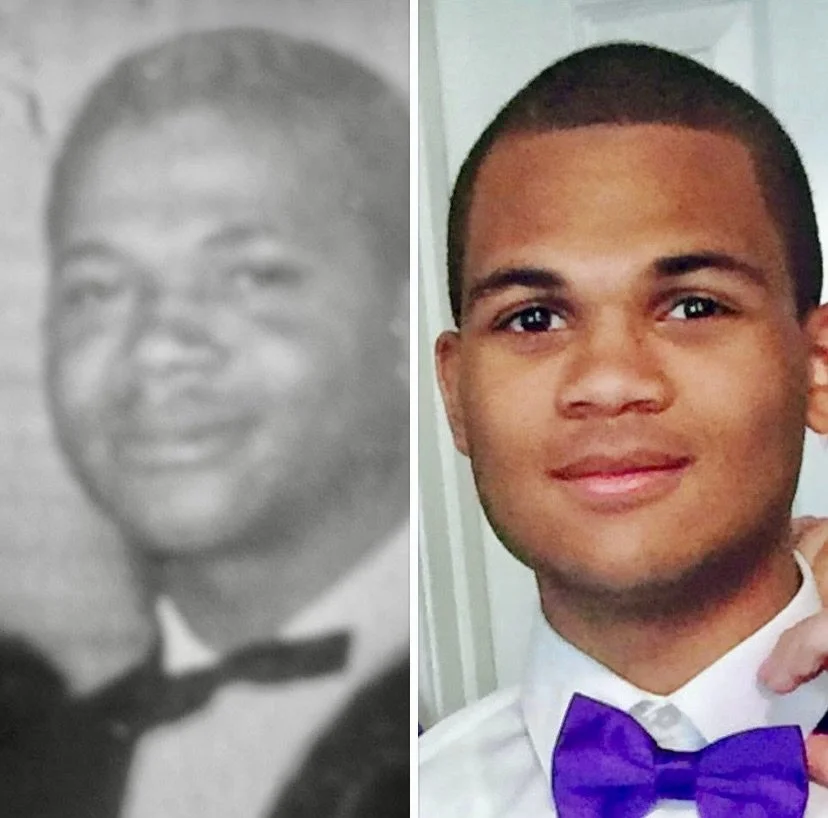

From the brass of Bull Bay, Kingston, Jamaica, (1941, at age 11) to the barracks of Britain (1948, age 18) — Roy Stephens carried both music and duty across the Atlantic. His service in the Royal Air Force made him part of the generation whose courage, creativity, and quiet endurance became the foundation of modern British culture.

Roots in Kingston: Matriarchs, Music, and Making Do

Roy Stephens’ heritage stretched across oceans, cultures, and centuries. His mother, Marie Weatherman Stephens, was born in 1890 in Jamaica and came from a family whose story reached back to the island’s colonial past, and even further back as Hispanic and Portuguese descendants.

Marie Carinenta Weatherman Stephens, was born on July 16, 1890, at 5 Georges Lane in Kingston, Jamaica, and lived to be 104.

Marie Weatherman’s mother, Caroline Rebecca Garsia Weatherman, carried a surname that hints at Hispanic roots through her father, Alexander Garsia (sometimes spelled Garcia), born in Kingston around 1836. Alexander, listed as “a pedlar” on his death certificate, died at age 63 in 1899.

Marie Stephens-Thomas with her Aunt Gwen Stephens at Gwen’s 100th birthday celebration in 2013 in Florida.

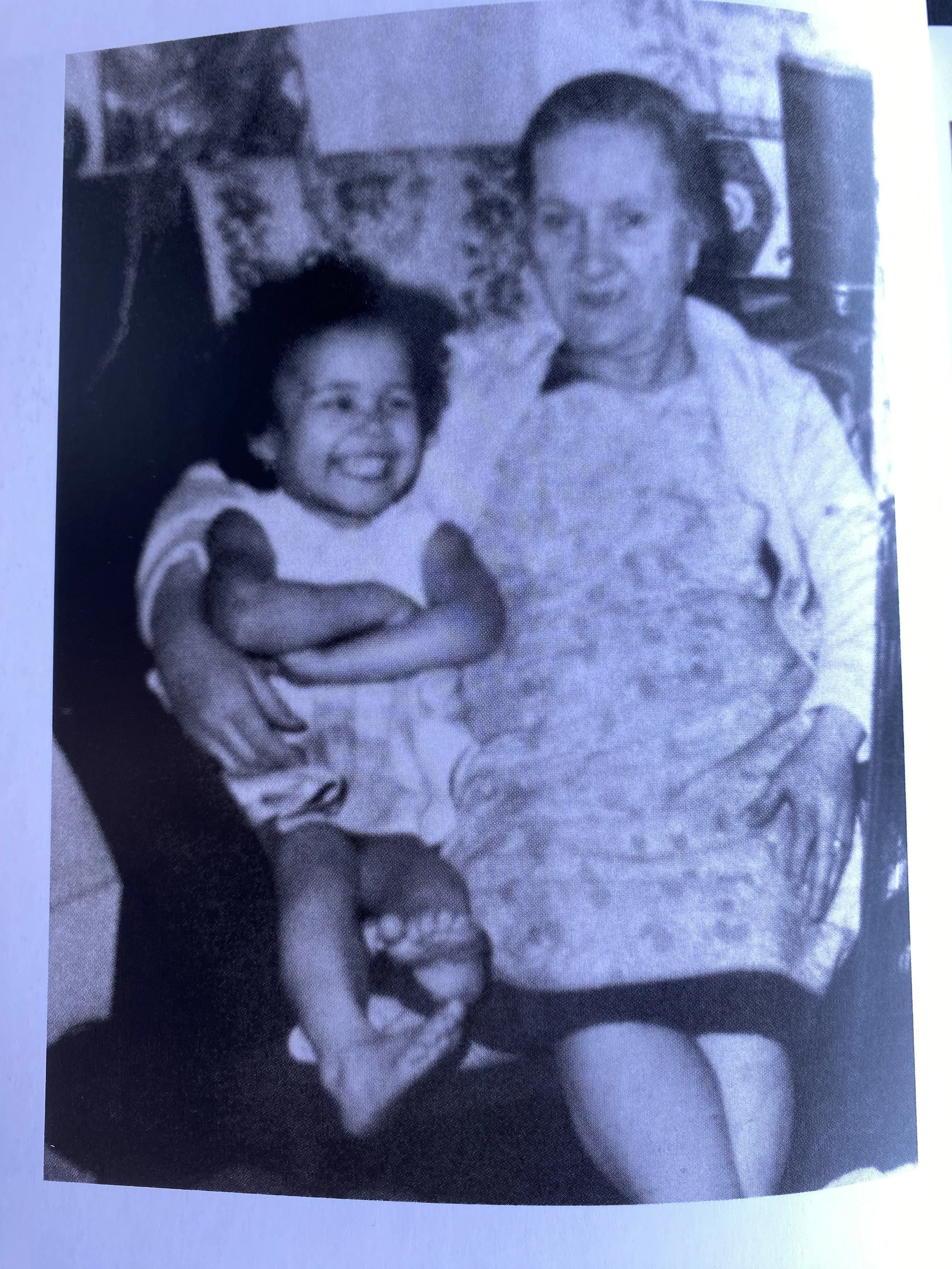

Marie Stephens-Thomas with Annie Kenny, her maternal grandmother.

Caroline’s mother, Catherine Garsia (Marie Stephens-Thomas’ great-great-grandmother), lived to be 70, passing away in 1905. Caroline had married William Augustus Weatherman, a tobacconist, on March 30, 1886. William was born in Kingston on April 20, 1850, and died there on April 13, 1893. They had three children: Ethel Quals (1883), Marie Carinenta (1890), and Louis Augustus (1892).

Though race was not recorded on Kingston public documents of the time, the family’s oral history preserves threads of Caribbean and European heritage woven through generations of artisans and musicians. Through Marie Weatherman Stephens, Roy Stephens, inherited a cultural lineage that predated emancipation in Jamaica — a reminder that their family’s story began long before their own names first appeared in official records.

And through Marie Weatherman Stephens, the family’s shared identity—rooted in music, craft, and matriarchal strength—took deep hold in Kingston and beyond.

Marie’s mother, Caroline Garsia Weatherman, and maternal grandmother, Catherine Garsia, were dressmakers, passing down both skill and self-reliance through the maternal line. This was a family where women held the fabric of life together — sometimes quite literally — while raising children in a society where survival often meant relying on one’s ingenuity.

On Roy’s paternal side, a parallel story of resilience unfolded. His father, Rudolph Adolphus Constantine Stephens, was born in Kingston in 1891 to Cecelia Morgan, and records suggest Cecelia’s own life was marked early by both joy and loss.

In February 1888, she had given birth to a son, Joseph, who lived only eleven days. Three years later in February 1891, she welcomed Roy’s father, Rudolph Stephens. The signature appearing on the death certificate of the infant Joseph and Rudolph’s birth certificate is Joseph Stephens, a ship contractor living in Kingston.

One year after Rudolph’s birth, in November 1892, Joseph Stephens died suddenly at the busy Victoria Market Wharf at just 36 years of age, taken suddenly by heart disease. His early death left Cecelia to mourn his passing and her infant son’s death while raising her surviving son Rudolph… in a household led entirely by women, a pattern of matrilineal strength that would echo through the generations.

Over the course of Rudolph’s life, his hands were always inside the music — first as a pianist, then a piano tuner and instrument maker, and by the time of his death in 1965, an organ builder. He was playing music while also crafting vessels that carried it, and teaching his sons everything he knew. For 25 years Rudolph played piano at a Kingston club, becoming famous locally.

It’s no wonder that his sons grew up fluent in the language of jazz, calypso, mento, and reggae. The violins, horns, and guitars their father made or brought into their home taught the Stephens brothers that craft was a form of pride and Black joy was worth preserving in every note.

Karl Stephens (X) on double bass with Jocelyn Trott’s Royal Caribbeans — one of Jamaica’s postwar dance bands that kept the island’s rhythm alive as new genres like ska and reggae began to rise. The Stephens family’s musical lineage ran deep — from handmade instruments to professional bandstands.

That inheritance — music as both discipline and delight — would ripple far beyond Kingston. By the time the next generation came of age and migrated to Liverpool, the family’s story had evolved beyond survival to shaping culture itself.

In 1991, the younger Marie sat beside her grandmother Marie on a sun-drenched veranda in Havendale, Jamaica, absorbing final words from a 101-year-old woman who had already outlived an empire. That moment — Marie and Marie, hand in hand — was more than a goodbye. It was a passing of wisdom, memory, and quiet strength — the kind of inheritance that doesn’t hang on a wall or play through a speaker, but lives on in how Marie carries herself in the world.

Early losses formed a quiet foundation beneath the Stephens family story; a reminder that resilience often begins in unseen places. From this soil, Marie’s Grandfather Rudolph grew into a musician whose talents would ripple far beyond Jamaica’s shores, shaping a family legacy of music and cultural pride that his children — the Stephens siblings — would carry forward in their own ways.

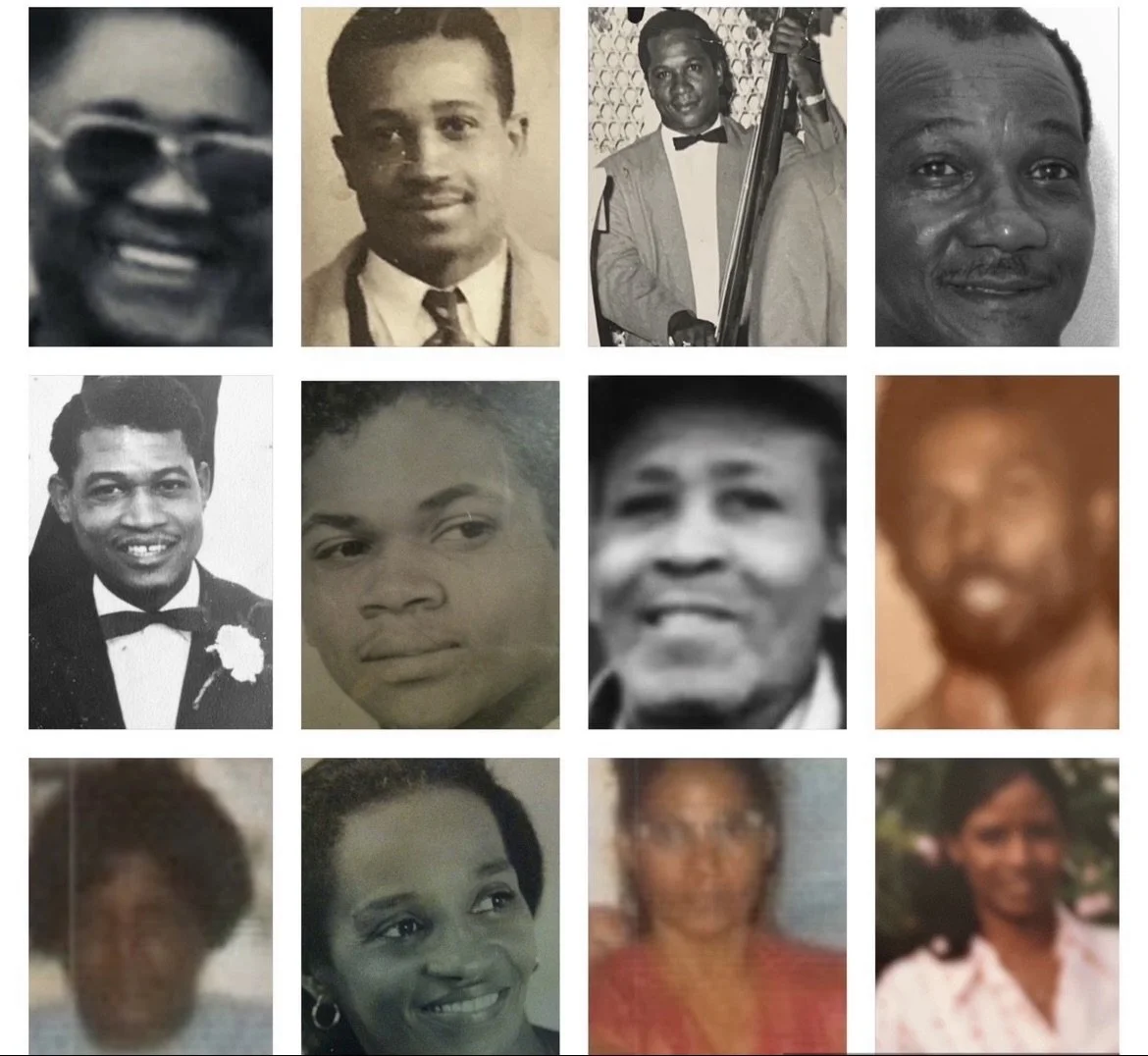

The Stephens Siblings of Jamaica

The Stephens siblings — twelve in all — carried music in their blood and courage in their suitcases. Some stayed in Jamaica, tending to home and heritage; others crossed the Atlantic, chasing new rhythms and new dreams in England. Together, they formed a living bridge between two islands and one unbreakable family line. From Kingston bandstands to Liverpool clubs, the Stephens family’s music helped shape the sound and spirit of two nations.

The Stephens siblings: musicians, entrepreneurs, and pioneers of the Windrush generation.

Top row (left to right): Ken, Delroy, Karl, and Owen.

Middle row: Les, Roy, Keith, and Neville.

Bottom row: Doris, Gwendoline, Mina, and Monica.

Marie remembers her father’s siblings as a constellation of personalities scattered between Jamaica, England, and the United States.

“Neville, Karl, Gwen, Doris, Monica, Mina, and Delroy all stayed in Jamaica for a while,” she said. “Delroy led a band in the U.K. before returning home to Kingston — and for years played piano at the Sans Souci Hotel there, where his music filled the nights.”

Karl, who stayed in Jamaica, played double bass while sisters Gwen, Doris, Mina, and Monica built their lives closer to home. Karl’s daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren now live in Florida and Middle Georgia, and Marie remains in contact with them

Gwen eventually emigrated to Florida with her family, where she lived to 104, just like their mother, Marie Weatherman Stephens. “I met Aunt Gwen again in Florida many years later,” Marie said. “We celebrated her hundredth birthday — and when she passed four years later, I went back for her funeral.” Gwen now has four generations of descendants living in Florida.

Marie’s earliest memories of the brothers are steeped in music and mechanics. “Ken owned the 101 Club,” she recalled. “He wasn’t a musician — he was a mechanic who fixed all the family cars. We used to visit him in Wales on weekends.”

Les played trumpet, too, and Owen, the saxophone, double bass, and other wind instruments. Keith wasn’t a musician, but like Ken, he kept the family cars running.

In time, six of the brothers — Ken, Roy, Les, Owen, Delroy, and Keith — were living in England and married. Marie met the rest of her aunts and uncles as a toddler on a 1964 trip to Jamaica, and again in 1972 when her family went back for a visit. The following year, her uncle Neville vacationed in Liverpool and was amazed by the large, close-knit family his older brothers had built there. Marie saw him once more during that visit, shortly before his untimely death at age thirty-nine.

For Marie, the legacy of those brothers and sisters was never distant — it was the world she was born into. Liverpool became her childhood backdrop, a place where her father’s trumpet and her uncles’ laughter blended with the vibes of a changing England.

Marie (second from right) with her mother and brothers Leroy, Tony, and Derek — the siblings who shaped her early years in England and carried forward the Stephens family’s love of music.

Growing Up Between Islands

Marie Stephens-Thomas grew up in Liverpool in a home where accents, skin tones, and cooking pots told the story of the world. Her Jamaican uncles and English aunts gathered in kitchens fragrant with curry, thyme, ginger, and garlic. Cousins of every shade ran underfoot, playing to a soundtrack of ska, reggae, and soul. On her mother’s side, her white grandparents offered a different heritage—her grandfather from Singapore, her English/Irish grandmother from Liverpool—weaving yet another cultural thread into the family fabric.

At eleven years old, Marie experienced one of those magical childhood moments you never forget. On a school field trip, she sat slouched in her bus seat, cheek pressed to the cool glass, when she spotted a convertible in the next lane. “There’s Paul!” she blurted out. “Hi, Paul!” It was Paul McCartney himself, with wife Linda in the passenger seat. They both smiled and waved before traffic carried them away.

“I was calling his name like I knew him,” Marie laughs.

That same year, Marie’s show-and-tell presentation outshone the usual rocks, dolls, and pressed flowers. She brought in 45s of reggae artists Honey Boy and Jimmy Cliff, told her classmates about the music’s rhythm and roots, and served them rice, peas, and chicken her mother had cooked—an authentic Jamaican dish she knew would make her uncles proud.

Marie’s connection to Jamaica ran deep. She first visited the island in 1964, at just one year old, perched on her father’s shoulder on the beach at Bull Bay. She soaked in the sound of the surf, the salt in the air, the music drifting from nearby, and the scents of jerk seasoning and pimento.

Marie’s first trip to Jamaica, 1964 — perched on her father Roy’s shoulders by the sea. For Roy, it was a return to where his story began; for Marie, a glimpse into Kingston, the city that shaped the Stephens family.

From neighborhood dances to downtown clubs, the brothers found their footing in the city’s vibrant music scene — guided by their father Rudolph Stephens — and even those who stayed in Kingston kept the music alive, passing its spirit down through generations.

“As a kid, I was immersed in Jamaican culture in Liverpool,” she recalls. “With the food and music, the family gatherings—it felt like Jamaica, though it was England.”

Marie’s English-Malaysian mother Babs had learned to cook Jamaican dishes from her husband Roy and her brothers-in-law. According to Marie, “she did it right.”

Years later, Marie met her now-former husband in the kind of chance encounter that becomes family legend. Like her mother and grandmother before her, she met him while he was serving in the U.S. military, stationed in England. His career carried the young family across continents — from New Mexico to Japan, then England and back to Japan for a second tour — before finally settling in Warner Robins, Georgia. There, they finished raising their children, seeing them through school, military service, and university.

In Middle Georgia, she has carried on her family’s Caribbean legacy, supporting local Reggae musician Dean Brown’s group, The Dubshak Band, and sharing her love of the genre. Her playlist favorites read like a roll call of greats: Bob Marley, Dennis Brown, Mikey Spice, and John Holt.

Life Abroad — The Military Years

As a military wife, Marie learned an art few people master: building a home on the move. In England, she had trained and worked as a registered nurse. But in Japan, without local licensing, she pivoted—teaching pre-kindergarten on base and pouring the same care into classrooms that she once gave to hospital wards.

“Some families lived out of boxes between transfers,” Marie says, ”sometimes for years. Not me. I unpacked everything after every move. I made each house a home first—then I looked for work.”

Across their military postings— abroad and in the U.S. — Marie kept music and food at the center of family life. The reggae, the Sunday rice and peas, the photo albums—anchors that turned base housing into a living archive.

Jamaica still feels like Marie’s heart-place so her upcoming retirement will be gentle rotation: Travels to visit kin in England and Jamaica, and then back to the USA where her daughter Jaichelle and son Jaeshaan live nearby, her daughter Candice lives in Indiana, and her son David, father of 6-year-old Izzy, lives in North Carolina.

Over the last couple of years, she’s been sharing books, photos, and stories with her newly discovered siblings — Wayne Stephens, Roy Halligan, and Andy Thomas — weaving them into the family cloth they always belonged to but didn’t know about, until now. Wayne, the family historian, has traced their lineage back through generations and assembled a detailed family tree. Though Marie and Wayne have yet to meet in person, they stay in touch and plan to finally meet next year.

Andy Thomas is the newest sibling she’s met — they were introduced just this year, and Marie has already seen him three times, often with her daughters. The Stephens traits were noticeable immediately, and an easy, automatic bond formed between them. Years earlier, at age twenty-six, Marie met her sister Paula, who had grown up playing the piano. Over time, the two became close, deepening their bond as sisters.

In recent years, those family threads have stretched even farther. Marie is in regular contact with one of her oldest Jamaican cousins, Howard Stephens, now 78 and living in Miami — the son of her late uncle Leslie. They often share stories and wisdom across the miles, swapping pieces of the past that make the family whole again. She’s also reconnected with Rick Stephens, another Miami cousin, and recently met Rick’s son and daughter, expanding the family circle still wider. “There are so many new and old family members I cherish meeting,” she says, her voice full of wonder.

Each new connection feels like one more note added back into the song. And through it all, her brothers Leroy and Derek remain the steady chorus — friends as much as family, whose laughter and loyalty have carried her through the years. “I’m so proud of them,” she says, “and we’ll keep living life to the fullest, in memory of our dear older brother Tony.”

A Call Across the Seas

Jamaica became part of Marie’s destiny decades earlier, way before her birth, when Britain called for workers after World War II.

With its labor force thinned by six years of war, Britain was still sweeping glass from the pavements and rationing tea in the late 1940s when it hung a “Help Wanted” sign across the Atlantic.

Recruitment posters promised steady work, good wages, and a place in Britain’s future.

With the British National Health Service (NHS) launching in 1948, and other industries short of hands, government ministers turned to the Commonwealth — to colonies and former colonies from the Caribbean to South Asia to Africa — for the hands and hearts needed to rebuild. The British Nationality Act of 1948 made these men and women citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies, free to live and work in “the Mother Country.”

So they came—some aboard the now-symbolic Empire Windrush in June 1948; others on later ships and planes—answering the call to drive the buses, stoke the boilers, and staff the wards of a brand-new NHS.

By the mid-sixties, thousands of Caribbean women were nursing in British hospitals; London Transport was actively hiring in Barbados and beyond to keep the capital moving. These immigrants were builders of a modern Britain in every sense: laying tracks and timetables, tending fevers and futures, and seeding the music, food, faith, and festival culture that would help define today’s UK.

From Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados, and beyond came young people with suitcases, Sunday-best clothing, and the music of their islands packed inside them. Some, like Marie’s father and uncles, carried instruments as well as toolboxes, their labor just as essential: they were rebuilding Britain’s spirit as well as its infrastructure.

In the decades that followed, the Windrush generation’s contribution proved immeasurable. Yet the welcome was complicated, rarely as warm as the advertisements had suggested.

Housing discrimination was routine, “color bars” blocked access to public spaces, and police suspicion stalked Black communities. Even as their labor was needed, the “color bar” shadowed daily life. It took the first Race Relations Act in 1965 to ban discrimination in public places, and immigration rules tightened from 1962 onward.

Still, many—Marie’s father Roy Stephens among them—met those closed doors with their own keys, building homes, businesses, and gathering places that nourished both their communities and the wider city.

And the long arc is unmistakable: the Windrush generation’s work powered Britain’s recovery—especially the NHS and public transport—and their cultural imprint endures from sound-system bass lines to Notting Hill Carnival’s bright procession.

That tension—invited to rebuild, then made to prove they belong—runs through families like Marie’s. And like Roy, many refused the limits imposed on them, building their own doors when none would open.

Looking back now, the pattern is clear: Britain gained far more than a workforce. It inherited a cultural and creative energy that reshaped its cities, its music, and its idea of itself. And families like the Stephens, rooted in Kingston but flourishing in Liverpool, became living proof that migration is never just about filling jobs—it’s about changing the very heartbeat of a place.

Storms in the Port City

Liverpool’s docks have always been a threshold — a place where ships and stories from around the world converged. But the same waters that carried music and spices, and brought together couples within Marie’s extended family, also brought racial tension that flared, again and again, across the 20th century.

The first great rupture came in 1919, when post-World War I scarcity and resentment turned white mobs against the city’s Black and Asian residents. In a week of violence that swept through the port, homes were ransacked, seamen were beaten in the streets, and at least one man was lynched. This was the Liverpool that would shape the Stephens family’s early years there — a city where your skin could make you a target, and your safety depended on the solidarity of your own community.

In 1948, when Britain passed the Nationality Act, granting citizenship to people from across the Commonwealth, six out of eight brothers from Kingston, Jamaica — the sons of Marie Weatherman Stephens and Rudolph Adolphus Constantine Stephens — rode the Windrush and landed in Liverpool, ready to work and to sharer music. They arrived into a city still nursing the prejudices of 1919, and now bristling at the influx of Caribbean seamen, dockworkers, and musicians.

Roy Stephens with his English-Irish mother-in-law Annie Kenny (right) and her sister Emma, Liverpool, c.1970s. In a city still wrestling with race and class divisions, families like the Stephens proved that love and kinship could bridge divides that politics and policy could not.

The Stephens brothers did what they knew best: they built places where music could dissolve suspicion, if only for a night. At The Palm Cove, the Embassy, and other venues they opened and operated, people of all races danced together to big band sounds, R&B, jazz, reggae, and soul. Inside, the rules were simple: respect the music, respect each other. Outside, the streets could still turn dangerous — but the clubs became beacons in the fog.

Racism in Liverpool did not burn out after 1948. It smoldered through the decades, and in 1981 it erupted again in Toxteth, where Marie was living as a teenager. The uprisings were sparked by police harassment under the “sus” laws — stop-and-search powers that targeted young Black people — but the deeper fuel was decades of joblessness, poor housing, and discrimination.

For Marie, who also carried the heritage of Ibrahim Kasad, her Singaporean Muslim grandfather, the riots were another reminder that in Britain, prejudice came in many shades — and could flare against anyone seen as “other.” She remembers those riots, remembers them erupting from a tired and frustrated populace when a young Black poet was arrested. People had had enough, and their anger burned and destroyed parts of Liverpool. Marie recalls staying home and listening for the latest news, looking out the window, waiting, hoping for the violence to subside.

Through every cycle of unrest, the Stephens family held their ground. When the music halls quieted and the nightclub lights dimmed, they carried that same spirit of resistance into new forms of work — building, repairing, and reshaping the city itself. Whether owning pubs, fixing cars, or keeping the trains running, they continued to contribute to Liverpool’s renewal. Their legacy wasn’t only in the rhythm of their past clubs, but in the enduring work ethic and pride that helped rebuild the very streets that once divided them.

Ken, Keith, and Roy Stephens.

But before those years of hard hats and calloused hands, before some of them traded bandstands for building sites and mechanic garages, the Stephens brothers had already remade Liverpool in another way — through sound.

The Stephens Brothers: Builders of Sound and Space

When the doors to Liverpool’s city clubs were slammed shut in the faces of Black musicians, the Stephens brothers didn’t knock twice. They built their own.

What started as a family of Jamaican musicians became a powerhouse of community and cultural defiance in Britain. From the Palm Cove on Smithdown Lane to The Embassy on Huskisson Street, Roy Stephens and his brothers were performers as well as visionaries — musical architects of a world that welcomed the very people mainstream society tried to keep out.

Roy and Babs’ son Tony carried that spirit forward as a DJ at The Embassy, spinning records for crowds that crossed every color line. In the process, the family’s stages began to draw white audiences too — people moved by the rhythm, the warmth, and the welcome the Stephens family created.

The Stephens brothers’ clubs were nightspots where Black Britons, West Indian immigrants, working-class Liverpudlians, and visiting American GIs could dance, drink, listen, and be seen. They brought in headliners like Nat King Cole, Dizzy Gillespie, and Coleman Hawkins. They kept the lights on long after the pubs closed. And they created the conditions for generations of musicians to find their footing.

As Ray Quarless of the Heritage Development Company Liverpool told The Echo, “We can’t get in clubs in town because of the colour of our skin, so we might as well do it here.”

That “here” became the heart of the L8 music scene, where venues like the Palm Cove and The Embassy stood as cultural outposts for more than 30 years.

Roy Stephens behind the wheel in Liverpool, outside the Palm Cove — the club he and his wife Babs opened in the 1950s, just four years after he arrived in England. They sold a carpet for £60 to help fund it. The Palm Cove the first Black-owned clubs in Liverpool, a place where jazz, ska, and reggae spilled out into the street and the Windrush generation came to dance, connect, and breathe home again. The building is gone now, but the legacy remains in the stories it left behind.

The Palm Cove, founded in the early 1950s by Roy and Babs, is remembered as the first licensed Black-owned club in Liverpool 8. It became a beacon, drawing not just Black Liverpudlians but white patrons from the North End and even visiting celebrities. And always, the Stephens brothers were the ones playing onstage—Delroy leading on piano, Roy on trumpet and organ, Owen on sax and double bass. Their band, The Commandos, originally a 14-piece jazz ensemble from Jamaica, became The Caribbeans—the house band at Palm Cove and the soundtrack to a rising Black British identity.

When the Palm Cove flourished, one brother or another would open more: the 101 Club, the Beaufort Grove, and eventually The Embassy Hotel and Nightclub, opened by Roy. Ever the entrepreneur, he ran his clubs while raising a family and playing late into the night.

“He always had a business,” Marie says. “At one point he owned Burger Bar on Smithdown Road. If one thing slowed down, he started something else — a club, a pub, even concrete garden statues.”

What she means is: he didn’t just run a club or a pub, he owned it. And he didn’t just sell concrete items, he made them — owning his own concrete factory on Jamaica Street in Liverpool 1.

Later, Roy would work construction in between all the other jobs.

What we see clearly is that Roy didn’t wait for a seat at the table to be offered — he built the table and served drinks on it, with Babs as barmaid and part-owner.

And when Black families in Liverpool were denied mortgages or leases because of their skin color, Roy created Jamaica Investments, Ltd., offering loans and support to Caribbean immigrants who wanted to put down roots. He made music and he made systems to help others.

In 1965, when the brothers returned to Jamaica for the funeral of their father, Rudolph Stephens, the national newspaper The Star ran a front-page article titled “Three Brothers and Their Success Story.” It wasn’t just a local-boy-done-good story—it was a declaration: Jamaica was proud of them. And so was Liverpool.

A 1965 article from Jamaica’s The Star celebrating the visit home — and success — of the Stephens brothers, Les, Delroy, and Roy, Owen, who rose from postwar migration to become club and restaurant owners in Liverpool and Manchester, England.

Roy’s leadership extended far beyond business. As founder and president of the Jamaican Merseyside Association, he organized fundraisers, connected people to resources, and built bridges between cultures. Even on the Empire Windrush itself, Delroy had organized shipboard concerts to raise money for six stowaways facing imprisonment. Their sense of justice was baked into their artistry.

Delroy stayed in Jamaica after their father’s death and later became the resident musician at Sans Souci Hotel there, performing for royalty and prizefighters and playing piano until two years before his own death in 1995. Owen toured Europe and once played on the same bill as Charlie Parker. Even the ones who didn’t stay in music left their mark—Ken at the Liverpool docks and Owen at British Rail.

Marie remembers it all from childhood, even now. She remembers the music, laughter, late nights, her dad playing the piano at his pub. And she remembers the clubs themselves.

“It wasn’t just a place to hear live music,” she said. “It was a place to belong.”

In the 80s and 90s, when developers tore down the buildings — one by one — where the nightclubs had formerly flourished, the city lost more than real estate. It lost its memory.

And that’s why Marie is telling her family’s stories now.

Building the Palm Cove: Love, Labor, and the Long Game

Before Roy and Babs built clubs of their own, there was The Stanley House — a cornerstone of Liverpool 8 and one of the few venues where Black Liverpudlians and immigrants could gather safely. Its opening wasn’t accidental; it came after years of lobbying by local Black leaders who demanded fair treatment and fought for public spaces where people of color could gather without harassment.

The Stanley House, 130 Upper Parliament Street, Toxteth, Liverpool — where Roy Stephens first met Kathleen “Babs” Arshet in 1948. Babs enjoyed listening as Roy and his brothers filled the ballroom with jazz and Caribbean rhythm. The following year, they married. Once a beautiful gathering place for Liverpool’s Black community, Stanley House was later left to decay and eventually demolished.

It was in that hopeful, hard-won space that Roy first played with his group, booked by their Welsh manager. The Stanley House became more than a gig — it was a community anchor where music dissolved suspicion and gave everyone a place to exhale.

Babs enjoyed listening to music there, a young English woman of mixed race who loved jazz and had a gift for making people feel at ease. On each visit, she watched Roy play — his trumpet shining under the low lights, the room alive with calypso, jazz, and laughter. That was where they met, where respect turned to affection, and where the partnership that would carry them through decades of business and family life began.

By 1952, with those early Stanley House lessons in their pockets, Roy and Babs sold their best carpet for £60, cashed in premium bonds, and scraped together enough money to open their first nightclub: The Palm Cove on Smithdown Lane.

Roy worked long days at the Ammunition Depot and odd jobs in Chorley, while Babs ran the kitchen and kept the club spotless. Together they turned a dream into a business — offering Caribbean food, music, and community to anyone who came through the door.

Inside, the Palm Cove pulsed with life. Tropical drinks flowed, the jukebox spun R&B, reggae, and jazz — until the Stephens brothers themselves took the stage. Delroy played piano, Roy’s trumpet rang out, Henry Desson kept time on drums, and singers like Billy Williams brought the crowd to its feet. Babs, ever the hostess, made sure everyone felt at home.

Les and June Stephens (foreground) with Roy and Kathleen “Babs” Stephens (center) at one of Liverpool’s annual Jamaican Independence dances, post-1962. Nights like these shimmered with pride and possibility — elegance, and unity setting time to a new era for the Caribbean community in Britain.

When the Palm Cove flourished, the brothers individually opened more venues: the 101 Club, the Beaufort Grove, and eventually The Embassy Hotel and Nightclub. Roy and Babs were shaping the music and nightlife of Liverpool’s Black community, creating spaces where color bars dissolved at the door. The Embassy became the place for carnival nights, boxing after-parties, and a cross-section of Liverpool life that couldn’t have mingled anywhere else.

As Ray Quarless told The Echo, “When they demolished these clubs, they demolished history.”

But not all of it. Some of it still lives on — in billboards in Piccadilly Circus on Windrush Day, in documentaries, in photo albums, and in the stories Marie tells her kids, her grandkids, and now, us.

The sound didn’t stop. It just moved.

Les, Owen, Roy, and Delroy Stephens, photographed in 1950s Liverpool during the family’s early musical years there. Decades later, this same image illuminated Piccadilly Circus in 2023, honoring the Stephens brothers’ legacy as part of Britain’s Windrush generation and its musical renaissance.

Roy Stephens’ Last Song

The music kept moving, but so did time — and eventually, it carried Roy to the final verse of his own song.

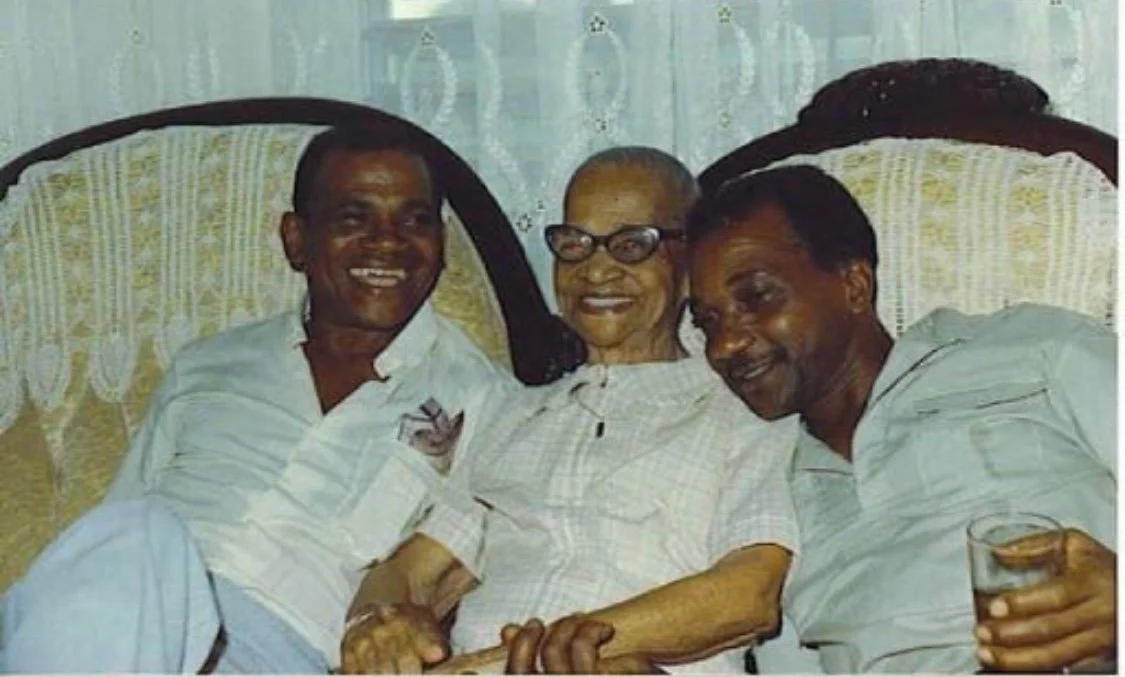

In 1990, the Stephens brothers boarded a plane bound for Kingston, Jamaica, to celebrate the 100th birthday of their mother, Marie Weatherman Stephens — the woman who had raised twelve children and kept the family steady through wars and migration.

Somewhere over the Atlantic, Roy clutched his chest, and the pilot diverted the plane to Nassau, Bahamas, where doctors confirmed he’d had a heart attack and they kept him hospitalized for ten days.

Back in Kingston, the family waited for Roy. When he was finally discharged from the hospital, he flew on to Jamaica, where the family at last honored Marie’s 100th birthday. She lived four more years, dying in 1996 at age 104.

Marie Weatherman Stephens celebrates her 100th birthday in Kingston, Jamaica, 1990, surrounded by her sons Roy (left) and Owen (right). It was a homecoming marked by laughter and legacy — just days after Roy suffered a heart attack en route to the island. Marie lived another four years; Roy only two, their lives forever bound by love and music.

After his recovery, Roy could no longer play trumpet with the strength he once had, so he turned to the drums—keeping time instead of melody, still inside the family rhythm.

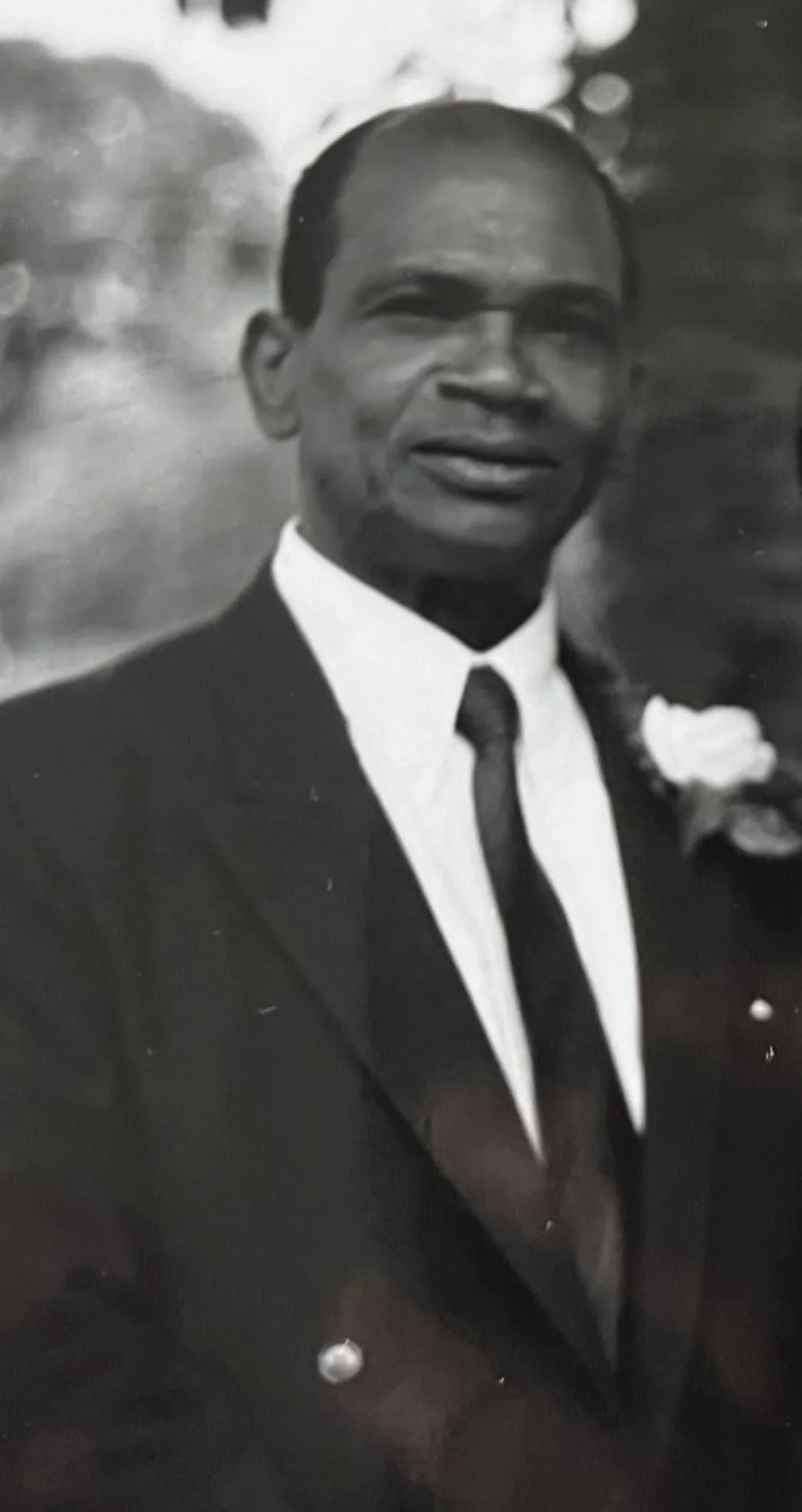

Roy Stephens, from Kingston to Liverpool. From his early days on the trumpet in Jamaica to his years as a club owner, father, and community leader in England, Roy’s life bridged cultures and generations. In the final frame, he stands with his daughter Marie.

Roy’s life had been a long climb — from the Kingston house where he learned music, to a postwar Liverpool where he fought for housing, started clubs when none would let him in, and kept a family fed and working in the face of constant prejudice. That kind of struggle might have worn down a strong heart, and though his father Rudolph had lived into his seventies and his mother lived past a century, Roy’s heart gave out too soon.

By 1992, the glamour days of Palm Cove and The Embassy Hotel were behind him. Roy owned a neighborhood pub and his son Tony helped to manage it, the kind of place where regulars knew each other’s names. One night, after the crowd thinned and the glasses were stacked, Roy sat down at the organ and played “Tenderly,” singing it with the warmth of Nat King Cole, his voice filling the pub. When the song ended, he said goodbye to his sons, left the pub, and that evening at home suffered a massive heart attack.

Roy was just 61. At his funeral, Babs — still close to Roy even after their divorce — slipped a wooden cross into his coffin. The cross had been a gift from Roy’s Welsh manager, who had booked their young group into places like the Stanley House.

After Roy died, Tony continued to run the pub and spin records as DJ, keeping alive the spark his father had lit decades earlier. Over the years, Tony became known as a snappy dresser — a wine-colored shirt, a wide-brimmed hat, that easy smile — and he ran the place with a loyalty that honored both his parents’ legacy.

Tony died in the spring of 2025, and Marie was able to share long, meaningful conversations with him during their final visit in the hospital.

In those final days, love found small, sustaining ways to show up. Brother Derek cooked Tony’s favorite Jamaican rice and peas, and Marie carried it in to him. Tony savored every bite. He had always loved the taste of home — the spice, the rhythm of his heritage — and his daughters, Mandy and Nicky, made sure that joy never left him. Even as his strength faded, their care filled the room with the comfort of family, of food shared, of roots remembered.

Tony knew Marie would soon be returning to the United States. As she turned to leave his room one final time, he called out softly, “Ned”—the name her aunt had teasingly called her since childhood, after the stuffed donkey Marie had named and loved as a little girl. Marie turned back and stayed a while longer, holding onto one more quiet moment between brother and sister. She turned back, the way she always does when called by love.

Marie with her brother Tony Stephens, who passed away in 2025 at age 74. Marie credits Tony and brother Derek as her two greatest mentors in reggae music appreciation. Tony was a DJ at the Embassy Club and later co-owned a pub with their father, keeping the family’s musical heartbeat alive in Liverpool.

Marie still hears Tony calling her Ned that final time — and her father’s hands on the organ keys. She survived them both, carrying the weight and the wonder of being the witness, the one who remembers and shares their storiers with the next generation. Their music and their love are still with Marie, shaping the way she tends to others now.

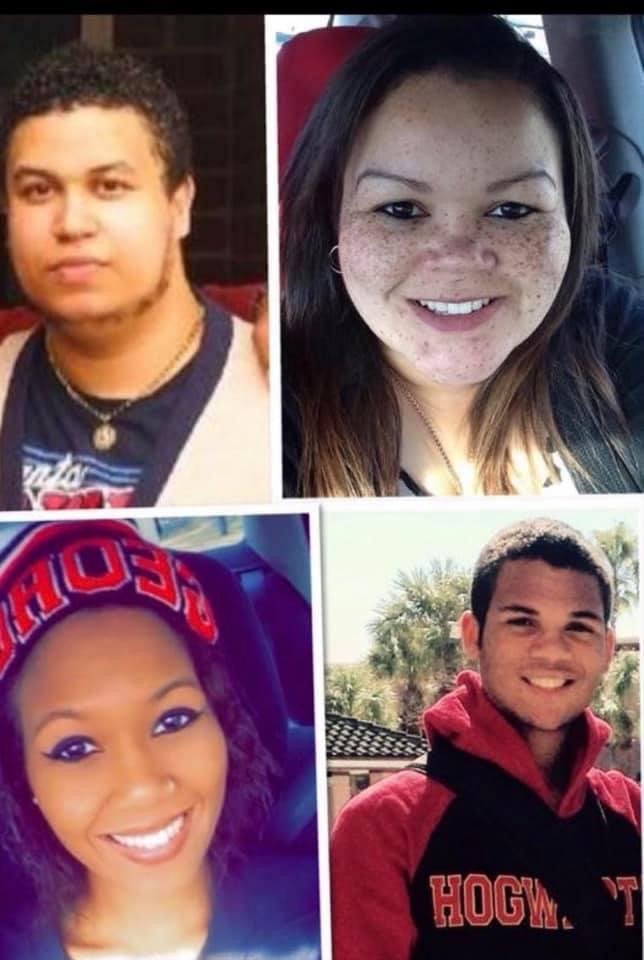

Music has always been a constant in the Stephens family — not just her father’s and uncles’ music, but her own children’s. All four played in high-school bands and still play today: David on trumpet, Candice on saxophone, Jaichelle on clarinet, and Jaeshaan on trombone. David and Jaeshaan both play guitar, and David writes and produces his own songs. Across generations, the family continues to play, make, and enjoy music — a shared rhythm that binds them no matter where they live.

Marie’s four children — David, Candice, Jaichelle, and Jaeshaan — grew up surrounded by music. All played in high school bands and still play today: David on trumpet and guitar, Candice on saxophone, Jaichelle on clarinet, and Jaeshaan on trombone and guitar.

Marie Stephens-Thomas visits with her 101-year-old grandmother, Marie Weatherman Stephens, at her home in Jamaica — the last time the two Maries would meet face-to-face. Across the lace table, a century of love and history passed between them in a single afternoon.

The Stephens legacy of sound didn’t end with Roy and his brothers — it simply shifted keys, finding new players and new stages.

The Last Visit

Marie hadn’t planned on saying goodbye. She was in Liverpool for a holiday, soaking up familiar streets and family chatter, when her mum, Babs, came down with a chest infection. The visiting nurse left antibiotics, but her medical training told Marie the sound of her mother’s breathing was wrong. She persuaded Babs to go to the hospital “just for a day or two” until the infection cleared.

Babs agreed, but with the stubborn practicality that had carried her through a lifetime. Before leaving, she slipped off her house shoes and set them neatly by her chair, certain she’d be stepping back into them soon.

On the ward that night, Babs acted more like a nurse than a patient, fussing over the women in the beds around her — pulling up blankets, straightening pillows — then shooing Marie and the others home as visiting hours were ending. “Go on now,” she said, ready to sleep so the morning would come and she could get back to her own clean house, which Marie had kept tidy for her.

Then, in the wee hours, Marie woke to pounding on the door. Merseyside police stood on the step. “Get to the hospital,” they said. At that hour, she asked them for a ride and while they normally don’t taxi citizens, they took Marie to her mother.

The city was hushed, the streets slick with night, and when Marie reached the hospital the corridors were dark. But she had worked there years before and knew the way, so she ran down the dark halls towards Babs.

Her brother Derek was already there in the dim room, machines humming low. Her mother was breathing. Marie caught Babs’ hand and held on as her mum crossed over quietly, at age eighty-five.

What began as a holiday coincidentally became the last vigil.

Babs passed away about ten years ago, leaving Marie grateful she was home when it happened — a rare grace after years of living oceans apart. “They said she was waiting for me,” Marie says softly. “She was waiting for me to come home from America.”

Kathleen “Babs” Stephens — bold, beautiful, and ahead of her time. A yong English woman of mixed race who fell in love with a Jamaican musician and never looked back. Together, she and Roy built clubs and raised children in postwar Liverpool, proving that love and courage could remake a city’s story.

Instruments That Talk: The Legacy of Handmade Music

Before the Stephens brothers ever cut across Liverpool with their big band swing, the music had already taken root in them — in wood shavings and wire, in the steady hands of their father Rudolph, a craftsman working by lamplight in Kingston.

Rudolph Stephens wasn’t just a player of instruments. He was a maker. A luthier in spirit if not in title, he carved his own violins, built guitars and organs, and passed down a mindset with the melody.

In a colonial world that rarely handed Black men tools of self-expression, he made his own. Each instrument was an act of defiance and a testament to the artistry woven into Caribbean survival.

That lineage echoes today in Middle Georgia, where Marie now lives. She still feels a magnetic pull toward musicians who play with that same soul-deep conviction.

“I listen to someone like Dean Brown,” she says, “and I hear home. My Jamaica home and my spirit home.”

Dean Brown, a reggae artist and bandleader based in Macon, carries on the tradition in his own right with The Dubshak Band. His music speaks to heritage, resistance, and healing. It’s no surprise that Marie has become one of his quiet champions, often attending his shows and sharing his music with friends and family across generational and cultural lines.

Afro-Caribbean music has always been more than entertainment. It’s a spiritual survival system — rooted in resistance, syncopated by slavery and faith. Mento, ska, calypso, and later reggae emerged not only from Africa’s drum traditions but from the hybrid lives Caribbean people lived under British rule.

In England, those rhythms adapted to their new setting—blending with jazz, skiffle, and soul. The Windrush generation remixed British culture. That remix didn’t stop there; it looped back across the ocean, amplified through Liverpool’s own sons — the Beatles — whose ears were tuned to the raw pulse of American soul and Southern rhythm. They mimicked Little Richard, idolized Otis Redding, and gave those sounds a new accent that, in turn, re-influenced the very South that inspired them.

When the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964, that sound wave crashed onto American shores with generational force. Boys in garages from Liverpool to Jacksonville picked up guitars, and many of those Southern kids — raised on church harmonies and soul radio — would grow into the architects of Southern rock, which was minted right here in Macon. The musical conversation had become circular, carried by ships, records, and dreams.

From the handmade violins of a Jamaican patriarch to the soulful guitar riffs in a Macon bar on a humid night—it’s all one ongoing composition. Marie stands at its crossroads: reggae in her heart, Liverpool in her roots, and Georgia seeping into her bones — the melody still moving through her.

From her early days in Liverpool to life in Georgia, Marie Stephens-Thomas has carried her family’s story wherever she’s gone. It’s alive in her smile as she shares that journey with her daughters seen here, Candice and Jaichelle, the next verse in a song that began generations ago.

The Diaspora Within: Love, Family, and Multicultural Pride

Marie Stephens-Thomas carries a global family tree in her heart—roots stretching from Jamaica to Malaysia, from the windswept Irish coast to the sunbaked sidewalks of the American South. Her heritage isn’t just a story of migration, it’s a love letter to the resilience of blended families and the beauty of difference.

One glance at Marie’s treasured family photos tells you everything. Skin tones dance across the spectrum—from luminous cocoa to creamy ivory. There are Sunday dinners with oxtail and Yorkshire pudding, patois mingling with Queen’s English, and babies lulled to sleep by both reggae lullabies and Merseybeat pop drifting through the radio. This is a family that doesn’t flatten its differences—it celebrates them. It frames them on the wall and sets them to music.

Stephens family gathering, circa 1975 — cousins, parents, and kin filling the frame with laughter and light — and Marie in the center, beaming. The family’s many shades of skin and spirit reflect their shared roots in Jamaica and Liverpool, where love always ran deeper than color.

Marie’s children have carried this joyful cultural fluency into the next generation. Her granddaughter Izzy knows who she is—not just by name, but by rhythm, flavor, and story. She knows the drumbeat of Jamaica and the warmth of Southern front porches. She carries the strength of ancestors who were never given an easy path but always found a way forward.

Izzy is the benefactor and product of all those brave crossings.

Marie Stephens-Thomas with her granddaughter, Izzy — the great-granddaughter of Jamaican musician Roy Stephens. At just six years old, Izzy carries a spark of the same creative spirit that has flowed through the Stephens family for generations, a living thread connecting Kingston’s music halls to today’s family gatherings.

Musician David with his daughter, Izzy — Marie’s son and granddaughter — the next generation of the Stephens family story. In Izzy’s smile and curiosity, Marie sees the same spark that has carried through her father Roy, herself, and her children… a reminder that the family’s rhythm still plays on.

Windrush Recognition: The Scandal and the Spotlight

For decades, the story of the Windrush generation lived quietly in community centers and the corners of British history books too often left unread. But in 2018, the Windrush scandal exploded into national consciousness, exposing how the very people invited to rebuild Britain after World War II were later denied legal status, jobs, housing — even their right to stay.

Despite living and working in the UK for decades, many Caribbean-born citizens were suddenly told they were there unlawfully. They lost their pensions, access to healthcare, and in some cases, were deported to countries they barely remembered. The government’s destruction of landing cards and documents — paper trails that could have verified their status — made their existence suddenly invisible. The scandal revealed not only bureaucratic failure but the deep veins of institutional racism still running through British life.

In response to public outrage, the UK declared June 22 — the anniversary of the Empire Windrush’s 1948 arrival — as Windrush Day. What began as a corrective gesture grew into a powerful moment of recognition and remembrance for Caribbean communities across Britain.

That recognition became strikingly personal for Marie when that towering electronic billboard in Picadilly Circus featured her father and his brothers as part of a city-wide tribute to Windrush pioneers.

The image didn’t just show musicians. It showed builders: the men who had poured their sweat and skill into creating spaces and refusing to be excluded, who served up jerk chicken and Chinese fried rice to a city still learning what multiculturalism tasted like, and who filled every corner of Liverpool 8 with music, laughter, and belonging.

“I didn’t know he’d be up there like that,” Marie said. “Seeing his face — my dad, right there in the open, after everything he went through — it just filled me up. I thought, ‘finally, they see we always mattered.’”

The photo used in the tribute captured the Stephens brothers in their prime: strong, sharp-suited, and steadfast. It was a declaration, a reminder that Black British history isn’t peripheral — it’s foundational.

For families like the Stephens, the Windrush scandal was a news story and a personal and generational wound. But Windrush Day gave rise to something enduring: a public platform for private pain, and a cultural spotlight for stories once told only around kitchen tables.

The legacy illuminated on those billboards remains brightly lit. And in the heart of that light is the story of a marriage and a family that made their own way, leaving a beat that still echoes from Kingston to Liverpool to Middle Georgia.

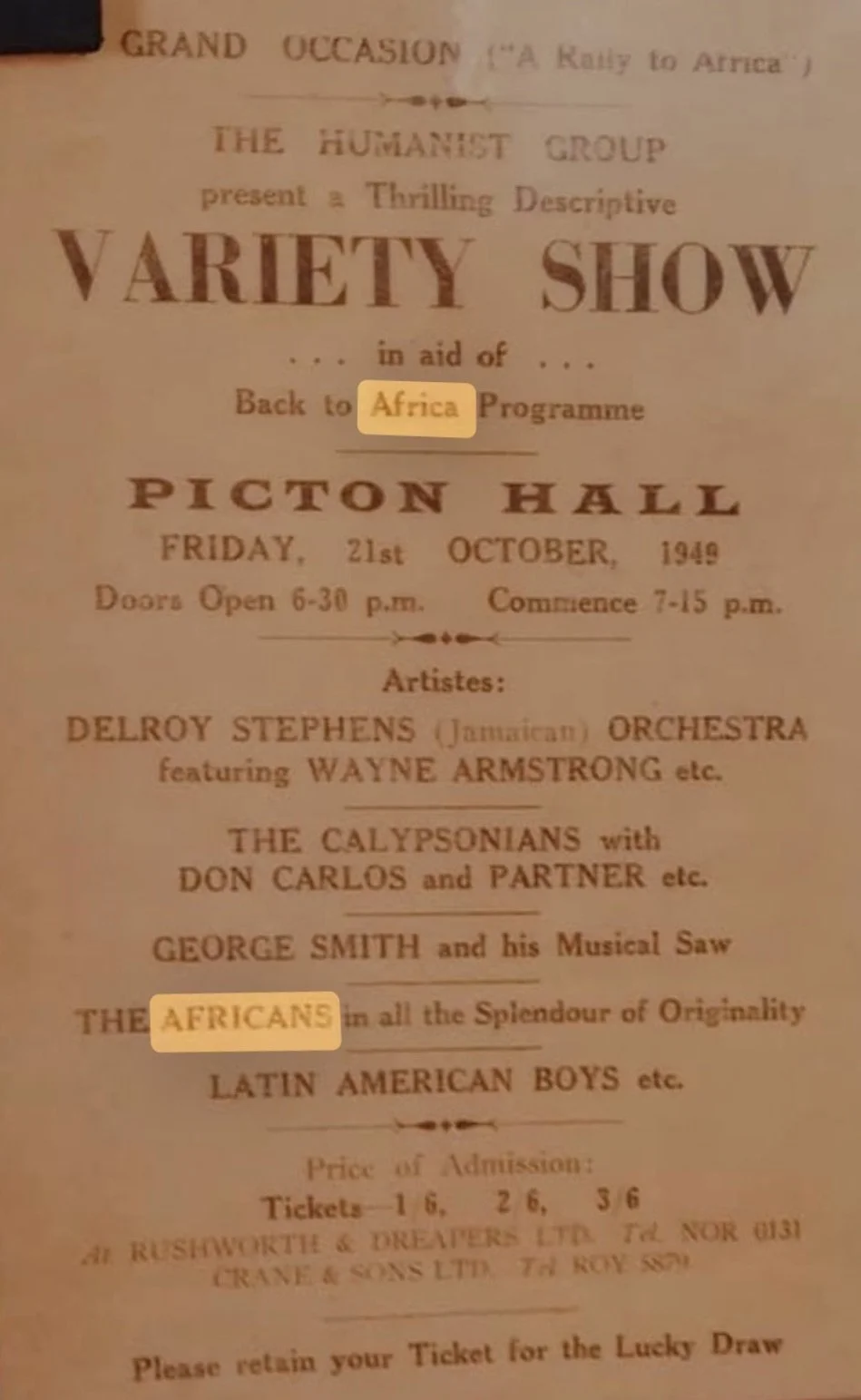

Liverpool, 1949 — A rare surviving flyer shows Delroy Stephens and his Jamaican Orchestra performing at Picton Hall for “A Rally to Africa,” one of the earliest postwar benefit concerts featuring Black musicians in the city. Decades before the Merseybeat boom, the Stephens brothers were already shaping Liverpool’s sound — blending calypso, swing, and Caribbean rhythms that echoed through working-class dance halls and laid the groundwork for the city’s multicultural music legacy.

The Listener

Marie is the thread. Her presence is unmistakable, in the way she remembers lyrics and makes artists feel seen.

She’s the weaver of past and present—Jamaica and Georgia, Liverpool and Macon, jazz and reggae, old world and new. She listens with her ears and her spirit. When elders speak of hard days or high hopes, she leans in. When a young musician takes the mic, she’s the first to nod along, offering that subtle encouragement that says: Yes. Keep going. This matters.

Among musicians, elders, and even strangers, Marie’s gift is her quiet tending. She’s the one who remembers who someone’s uncle played bass for. Who knows when to bring a story or a moment of stillness. In doing so, she keeps the soul of the music alive—not the sound, but the why.

There’s an old belief that music is a living thing—it needs to be heard to exist, and felt to breathe. If that’s true, then the listener holds as much power as the player. And in that sacred equation, Marie’s role becomes luminous.

Left, Roy Stephens in 1950s Liverpool, and, right, his grandson Jaeshaan, son of Marie, in the United States decades later — a striking likeness that bridges the family’s Jamaican, British, and American roots and sharing the same unmistakable grace and presence.

Dean Brown’s Place in Marie’s Story

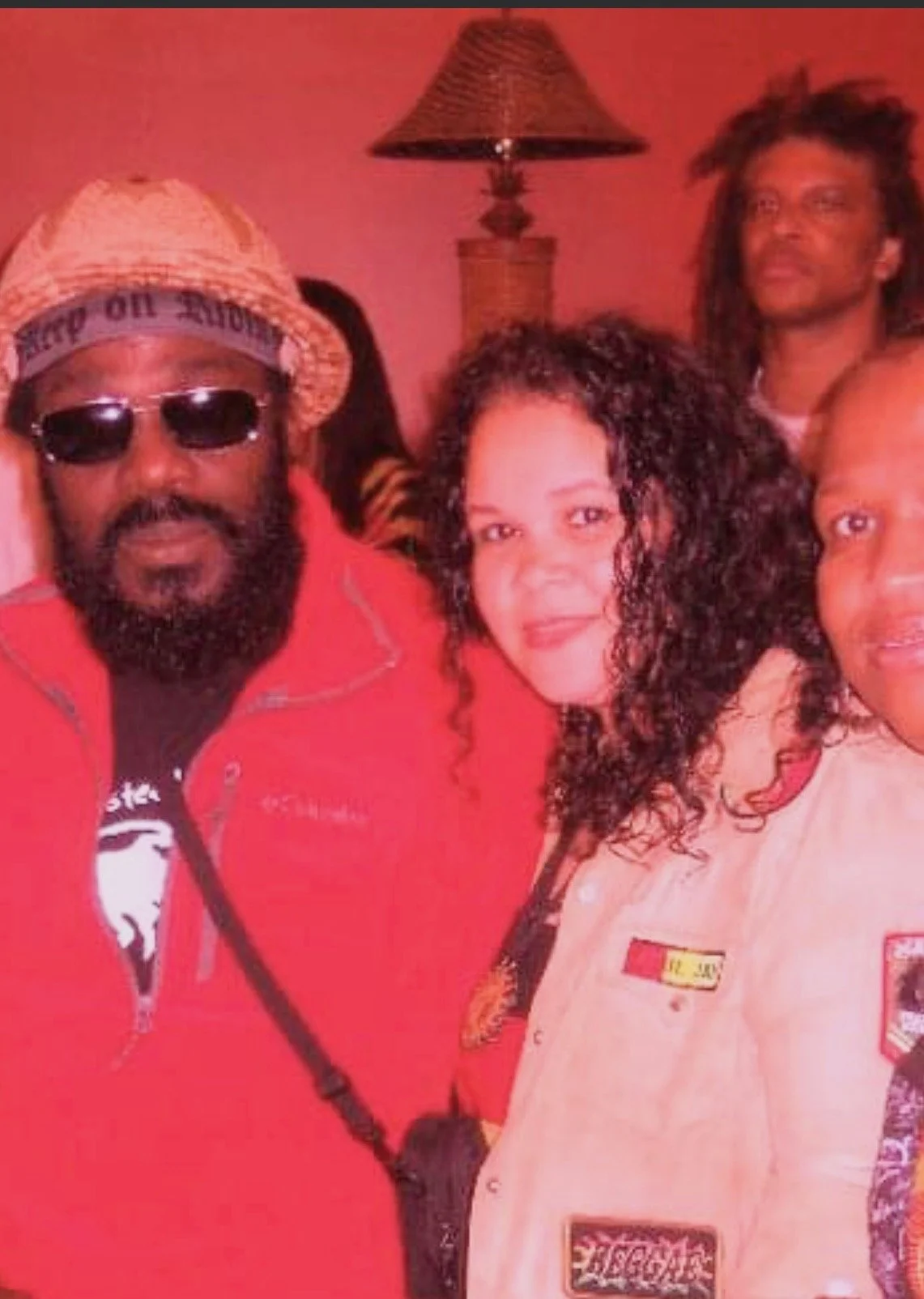

Nearly twenty years ago, Marie met reggae artist Dean Brown on a Macon street, and she’s been one of his steadfast supporters ever since. She’s brought her family — including her mother when she visited from Liverpool — to see him perform, bought the band’s t-shirts, and cheered them on through every lineup change. The current incarnation of Dean’s live reggae ensemble, the only one in the area, is called The Dubshak Band.

“When I hear Dean play, it feels like home,” Marie says. “He’s been part of my Macon story for nearly twenty years — the music reminds me of Liverpool, of Jamaica, of my father’s trumpet. That’s why I keep showing up.”

Dean, moved south from upstate New York at age 11 and eventually made Macon home, carving out a place for himself in the city’s eclectic music scene. His band blends reggae, jazz, and soul, and on the night I joined Marie, they sounded tight, playful, and deeply in sync. In 2011, Dean’s band opened for The Wailers — Bob Marley’s legendary group — and he’s since played guitar with Ky-Mani Marley, Bob’s son.

At one point Marie’s cousin Janiece, visiting from Liverpool, took the mic and sang “Killing Me Softly,” her soft, clear voice carrying the family’s musical legacy forward in an unexpected Georgia hotel lobby. Her grandfather, pianist and bandleader Delroy Stephens, and her mother Janet Stephens, would definitely approve of Janiece’s singing, and the several albums she has recorded.

Janiece’s visit in Middle Georgia added a rare, shimmering moment — one that briefly braided Liverpool, Jamaica, and Macon together in a single song. When she passed the mic back to lead singer Emily Amos and the music rolled on, the night returned to Dean’s steady groove, reminding everyone why his presence in Middle Georgia matters so much.

In addition to leading The Dubshak Band, Dean spent more than two decades working in Macon’s television industry and now works as a photographer, videographer, and composer, keeping him deeply connected to the city’s creative life.

For Marie, Dean isn’t just a local favorite — he’s a living link to the rhythms of her Jamaican roots, a reminder that the music she grew up on is still alive, still onstage, and lighting up Middle Georgia.

Dean’s music is just one of the many creative sparks Marie has championed over the years. Her instinct for recognizing soul and sincerity in a performer has carried from the streets of Macon to the stages of the wider world.

Years before Teddy Swims became a global soul sensation, Marie met him during his early YouTube days — a young artist from Atlanta still finding his way. The two met in 2019 in Atlanta, just as his star was beginning to rise, and she told him, “I believe in you; you’re going to make it.” Since then, Marie has followed his rise with pride, attending concerts and celebrating each new milestone, illustrating her lifelong instinct for recognizing promise before the spotlight arrives.

Marie Stephens-Thomas’ British family meeting Macon reggae artist Dean Brown.

Marie with singer-songwriter Teddy Swims, Atlanta, 2019. She first met him during his early YouTube days, long before his worldwide success, and has been his champion all the way. He’s one of her favorite Georgia artists

The Beat Lives On

Music spills into the streets here — off porches and out of juke joints, from gospel choirs and summer stages. And somewhere in that hum of sound, Marie is there. Maybe she’s smiling behind the lens of her phone, capturing a moment. Maybe she’s dancing a little to a rhythm that traveled oceans and eras to find her. Maybe she’s just listening — deeply, lovingly, the way only someone with a sacred ear can.

She carries it all: the jazz chords her uncles played in Liverpool nightclubs, the sound of a piano tuned by her grandfather’s patient hands in Kingston, the voices of elders who survived storms no charts ever tracked. She carries the heat of jerk chicken on a Smithdown Lane night, the clink of glasses at The Embassy Hotel, the laughter of a crowd that knew they belonged inside those doors because the Stephens family built the doors themselves.

Here in Georgia — where she tends to the elderly, checks in on musicians, and shows up for every show that matters — Marie continues to honor those who came before her. The journey runs in one unbroken line: from a Kingston workbench where an organ builder shaped sound into being, to a Liverpool dance floor where her father’s Caribbean rhythms met Merseybeat and her mother made everyone feel welcome, to a Macon bar where soul lives and reggae still lifts people to their feet.

Today, four generations of Stephens descendants are alive across Jamaica, England, and the United States. From Roy and his brothers came children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and even great-great-grandchildren, each carrying forward more than a name. Through their work and music, the Stephens family carried pieces of Caribbean culture with them — shaping communities, enriching the sound and spirit of the places they settled, and leaving traces of Jamaica’s creative pulse wherever they landed.

Marie speaks with pride about the many nieces, nephews, and cousins who came after her — a far-flung family now living all over the world, each adding their own verse to the Stephens story. Her four children — Candice and David from her first marriage, and Jaichelle and Jaeshaan from her second — each carry forward that same creative rhythm that has pulsed through the Stephens line for generations. Together they reflect the global path their mother has walked, from England to Georgia, from reggae to gospel, from roots to renewal.

And now, through Marie, that legacy plays out in quiet harmony — in her family, her friendships, and the faith she shows in young artists who may never know how far back their roots really go. She cheers on the Dean Browns of the world and keeps the beat of her ancestors alive in every act of encouragement.

So the next time you hear reggae spilling out of a Macon bar, or a gospel choir raising the roof, or a Southern rock guitar solo crying through the pines, remember: that sound carries all the way back to Africa.

Roy’s song, Tony’s voice, and Babs’s careful hands are all still with Marie, steadying her as she walks the halls of the memory care ward. These days, watching her children make their own music, she knows the family’s story is still unfolding — not just in sound, but in the blending of rich cultures, in the music’s migration with her family, and in the joy of finding ways to belong wherever they go.

What her parents and grandparents began still plays through Marie — a gentle harmony, steady and sure. A song always ready to begin again.

Marie Stephens-Thomas with her four children — David, Candice, Jaichelle, and Jaeshaan — representing the generations and journeys that continue the Stephens story. Marie’s vision keeps their far-reaching family close, weaving connection through every message and memory. Her dream of a family reunion is more than a wish; it’s a reflection of the unity she remembers from her childhood and nurtures across distance and time — a living chorus with its beat in Jamaica’s sand, Liverpool’s River Mersey, and Middle Georgia’s red clay.

All photos courtesy of Marie Stephens-Thomas. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

About the Author

Cindi Brown is a Georgia-born writer, porch-sitter, and teller of truths — even the ones her mama once pinched her for saying out loud. She runs Porchlight Press from her 1895 house with creaking floorboards and an open door for stories with soul. When she’s not scribbling about Southern music, small towns, stray cats, places she loves, and the wild gospel that hums in red clay soil, you’ll find her out listening for the next thing worth saying.