The Morning After

On a cold December night in 1949, Bill Allman was killed. This series follows the ripple effects — from courtroom to clemency, from grief to guitars — and the music that rose from it all... music that outlasted everyone who played it. Read the full series introduction here.

The humid salt air of East Ocean View clung to everything, even on a morning that promised rain. On 37th Street, a boy named Buddy Green watched men deliver ice from a big truck and listened for the nearby streetcars rattling down Granby. He was ten when the hurricane came, sweeping over Willoughby Spit, dropping tons of sand on the streetcar tracks, and ripping shingles from rooftops. Even then, Buddy was learning how to rebuild.

He dropped out of Granby High before he could graduate, chasing a job that would put tools in his hands and money in his pockets; plumbing paid better than books. He worked the Navy base, the tight new grid of military housing, dreaming of steady wages, and eventually buying the only car a young plumber could possibly swing at the time — a used Model A Ford.

In 1942, at nineteen, the Army gave Buddy a number and a uniform. He was wiry and worked without complaint. That made him useful. They shipped him to Camp Howze, then to Italy with the 349th Infantry — the Blue Devils. In the Apennine Mountains, he cleared roads with sweat and sometimes blood, chasing retreating Nazis across stone villages littered with mines and booby traps. Buddy’s job was to find the mines — and live.

In Rome, he saw the Pope. In Naples, he married Marie, a laundress with dark hair and defiant eyes. For a while, they were happy. After the war, they came home to Norfolk. East Ocean View. The streetcars still rattled, at least for one more year. The storms still came. Buddy fixed pipes for E.G. Middleton and talked about the war the way most men did then: only when cornered by memory or drink.

And then, on December 26, he decided to rob two fellow veterans. It didn’t have to end in murder, but it did.

Buddy got into Bucky’s car on that isolated dirt lane and sped away, leaving Bill Allman bleeding in the muddy field and Bucky seeking help.

Buddy could have gone anywhere. Mexico, maybe — the place whispered about by men on the run, a country you could slip into if you had the cash, the nerve, and a good enough lie for the border guards. He might have stopped at Marie’s door to say goodbye, dragging her and their baby daughter into his mess.

Or maybe he pictured Quebec, where his father’s people came from — a cold land where a man could disappear into lumber camps and mining towns and never be asked for his papers. He could have headed north to Baltimore or New York, found a boarding house and a shipyard job under a new name, a place where no one cared what he’d done in Norfolk.

But Buddy didn’t go anywhere at all. He just drove three miles down familiar roads — far enough to think, not far enough to vanish — and he was still in East Ocean View.

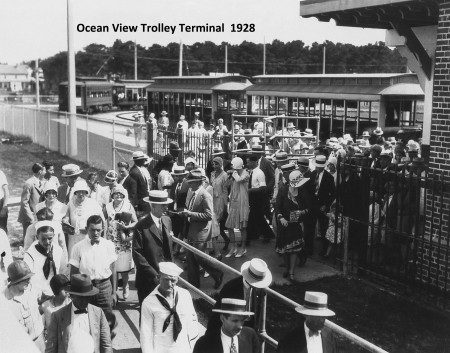

Ocean View Trolley Terminal, 1928. Once called the “Coney Island of Virginia,” East Ocean View was originally designed as a summer resort community before being absorbed into Norfolk.

Photographer unknown.

Boyhood on the Spit

Not yet fully Norfolk, East Ocean View belonged to Princess Anne County, a spit of land half salt marsh, half promise. Buddy knew every rutted lane, every bend that led to nowhere. As a boy, he’d learned them by heart, growing up in a place locals once called the “Coney Island of Virginia.” The neighborhood had been laid out as a summer resort, a getaway for beachgoers and thrill-seekers, and Buddy’s favorite thing back then had been the roller coaster.

When he’d come back from war to these same tracks, tools in his hands, pipe wrench clanging against his hip, he had believed a man could build a life and grow a family here, if he didn’t let a storm or the tide drag him under.

In the early hours after the murder, Buddy pulled into the yard of his parents’ house on Chelsea Avenue. He left Bucky’s car outside like a marker, walked through the front door, and lay down in his childhood bed, a .22 rifle within reach.

Why home? Why not Mexico, Canada, a big city?

Maybe Buddy knew there was nowhere left to run. Maybe the same part of him that knew how to rebuild knew when he’d finally broken something beyond repair. Maybe it was cowardice, or a final flicker of hope that Mama would make it right, that Daddy would say the right thing, that sleep could unmake a bullet and a grave.

Maybe Buddy wanted to be found, still small enough to fit in the story he’d been telling himself all his life: that home was safe, even now. And if it proved unsafe, at least he knew he could talk himself out of anything, including murder.

The house he and Marie shared stood right next door. But he didn’t go to his wife. He didn’t cradle his sleeping daughter goodbye. He went home to his mother’s house instead, the place where the weight of two families — the hard-pressed Greens and the salt-honed Fitchetts — lay thick in the walls. Maybe he thought he could crawl back into boyhood, into the bed where he’d been forgiven.

Chief Ivan Mapp at the Door

Before the sun came up over Princess Anne County, Chief Ivan Doughty Mapp pulled into that same yard. Chief Mapp stood for the strong bones of the community. He had been a soldier too — a World War II veteran, like Buddy, but one who came back and built things up instead of tearing them down.

Mapp was more than a lawman; he was the kind of Virginian who belonged to every lodge, sat on every board, opened every town parade. His father, his grandfather — three generations or more of Mapp men buried under the same tidewater sky. They’d cleared roads, kept the peace, kept order, kept records, married neighbors, buried each other in neat rows under Methodist crosses and Masonic squares.

The county leaned on men like Mapp to keep order when blood ran hot or cold.

Ivan, Sr. had farmed the salt flats, raised his children to join the civic spine of Virginia’s tidewater towns. Ivan Jr. — the Chief — chaired commissions, stood at courthouse doors and when a storm hit the county, he boarded windows, gathered neighbors, rode it out together.

Pillars don’t run.

The man leading the search was Chief John Mapp, Norfolk’s top lawman, whose reputation for discipline put the entire city on alert.

Chief John Mapp

Norfolk police chief who oversaw the manhunt for Buddy Green after his escape.

The Green blood was different — full of men who learned to carry weight until it broke them. Buddy’s grandfather, William John Green, left Quebec for the Norfolk docks. He bent his back to the ships and furnace heat to feed his family, hoisting crates under the Norfolk sun. By the time his grandson raised a gun, the hands that once held hemp ropes and sacks of coal were long stilled. William Green’s sons had scattered — roofers, plumbers, lone men dying in vacant houses or on borrowed beds. There was never quite enough order to hold the Green family together; the cracks showed in busted hearts and bottle bottoms.

Even his Mother’s side, the Fitchetts — with their proud tugboat captains and lodge roots — couldn’t keep Buddy from becoming the last Green man to shatter under pressure.

The Coming Storm

Mapp didn’t know exactly what he and his deputy would find that morning on Chelsea Avenue. Maybe nothing, maybe a standoff, maybe a desperate man gone to ground. But when Buddy’s parents, William and Sadie, answered the door — the old house thick with kitchen smells and the hush that comes when shame crosses the threshold — they didn’t fight Mapp or keep him out. Resigned, they showed Chief Mapp down the hallway lined with family photos. There, in Buddy’s old room, Mapp found the murderer sleeping under a blanket, the rifle tucked close, as if it were a toy he’d never outgrown.

Buddy’s mother Sadie Fitchett Green would later become hysterical in court, screaming that her son was framed — that the good boy she’d raised, the grandson of a tugboat pilot and a Masonic lodge member, couldn’t be a killer. But that morning after the murder, she said nothing.

The door cracked open. Mapp stepped in. A good man finding a broken one, one county son arresting another.

All the roads had led Buddy back to the only pillars he had left — a mother who’d yell out in court to defend her son, and a father who’d open the door to the law because he’d never learned how to lock it.

Buddy didn’t run after murdering Bill. He just drove until the road bent him back to where a man could lie in his childhood bed with a weapon for protection and pretend the storm might pass him by. But this was one storm Buddy couldn’t shelter from for one more minute; after all, East Ocean View was still half salt marsh and half promise.

When Chief Mapp stepped back into the dawn with Buddy in handcuffs, he knew the next storm would come in the courtroom — neighbors whispering, families testifying, mothers pleading, and Buddy sitting small and guilty, like the roller-coaster-riding boy he once was.

The story that came next — the trial, the truths Buddy told or swallowed — is harder to pin down. A 1970s fire in Norfolk’s records burned through so much: court transcripts, military files, documents that might have told us exactly what words were said in that bright courtroom, or how Bill Allman had earned his stripes in the Army. I still look for them by sifting through archives and newspaper clippings. Unfortunately, some stories stay buried under ashes and silence. So I piece fragments together as best I can because the story isn’t entirely erased. It just makes us lean in closer to hear those distant echoes from old Princess Anne County, a liminal place that wasn’t fully city, nor fully county, but the perfect mirror for the rest of Buddy’s story, with a storm always waiting just offshore.

About the Author

Cindi Brown is a Georgia-born writer, porch-sitter, and teller of truths — even the ones her mama once pinched her for saying out loud. She runs Porchlight Press from her 1895 house with creaking floorboards and an open door for stories with soul. When she’s not scribbling about Southern music, small towns, stray cats, places she loves, and the wild gospel that hums in red clay soil, you’ll find her out listening for the next thing worth saying.