Kirk West: A Life in Focus, Behind the Lens and Behind the Scenes

Held Here: Presence in Profile is a series highlighting the artists, archivists, entrepreneurs, and visionaries who have shaped Macon’s cultural identity. Each subject is someone who planted roots and, through their work and presence, have helped preserve the city’s creative spirit for the next generation.

This installment features Kirk West, longtime tour manager and photographer for the Allman Brothers Band (ABB), co-founder of Macon’s Big House Museum, and a tireless documentarian of Southern Rock history. From the blues clubs of Chicago to the back roads of Georgia, West has spent decades behind the lens and behind the scenes—building an archive, telling stories, and keeping that Southern Rock legacy humming.

Chicago or Bust

On cold Chicago nights in the late ’60s, Kirk West wandered down South Side streets, camera in hand, neon buzzing overhead. Inside smoky clubs, the air would split open with the scream of a Stratocaster. He was there to party… and capture images.

Muddy Waters. Howlin’ Wolf. Buddy Guy.

The Chicago blues scene was more than a sound; it was an electric sermon. And Kirk, barely out of Iowa, was ready to listen. That's why he had sought out Chicago in the first place.

It would take him a few thousand more miles, a few more lost highways, to find another city that preached its own gospel— this one in the South — and welcomed him as one of its keepers.

Chicago to Macon, from one electric sermon to another.

Somewhere between a roadie and a rock prophet… Tour Mystic Kirk West in the early 90s, conjuring cosmic order from backstage chaos. (Image source: Alan Paul’s Substack. Photographer not listed.)

A Documentarian

Kirk West, who turns 75 this October, has been taking photos since age ten, when his grandmother handed him a little, green plastic camera loaded with 620 film. The instinct came naturally: his father, though mostly absent after his parents divorced, had been the school photographer in his own youth, shooting yearbooks and local events. For Kirk, the camera became a way to see the world differently.

By thirteen, he was already making money with it. Working afternoons at a Chrysler dealership in his hometown of Nevada, Iowa, he fell in with their drag racing team. On weekends he’d tag along as a gopher, snapping shots of the cars in action. Some of those photos even sold to the local paper, since the team was a winner and a source of hometown pride. For a boy who loved machines, it was the perfect collision: grease under his nails, film in his hands, and his first taste of turning a passion into a livelihood.

"Film was expensive," Kirks says, "so I photographed what was important to me, like my model cars, and then just took snapshots of my life for years. Later when I was able, I bought real hot rods. Then my life became concerts and music.”

Even as a kid, Kirk was collecting things, curating, documenting—tiny model hot rods lined up like a starter fleet. Later, he graduated to the real thing: fire-red muscle cars and street rods that looked fast even when parked. It wasn’t just a hobby—it was a reflection of something deeper, something shared by a whole generation of boys raised on drag strips, drive-ins, and the myth of the open road.

For Kirk, hot rods weren’t just machines. They were expressions—of individuality, rebellion, motion. The same could be said of the photographs he took and the music he chased. All of it pulsed with energy. All of it asked the same question: Where to next?

Hot rods, drag racing, rock 'n' roll, and the perfect shot through a camera lens—they each captured Kirk’s vision of freedom in their own way. They were about framing life in motion, holding on to speed and style, and the thrill of becoming.

Kirk embodied that spirit behind the wheel and behind the lens. And later inside the Allman Brothers Brotherhood.

One of the deepest through-lines in Kirk’s life is his instinct to preserve and elevate—to give fans a legacy they can hold in their hands. Kirk might have been riding shotgun but he was driving the record-keeping, archiving, and storytelling.

That takes consistency, and vision.

Photos throughout by Kirk West/Retro Photo Archive, unless otherwise noted. Captions in quotes come from Kirk’s Intragram posts: @kirkwestfotos

“I’m a little farm boy from Iowa, and there wasn’t a lick of blues in our county,” Kirk says. “Paul Butterfield’s East/West record changed my life.”

In his book The Blues in Black and White, he put it even more bluntly: “I moved to Chicago in ’68 from a little Iowa farm town, because I’d heard Paul Butterfield on the radio…I knew that Butterfield was in Chicago, and that’s where I wanted to be.”

Fresh out of high school, Kirk plunged into the turbulence of 1968. That summer he witnessed the chaos of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago by being at the convention! Chicago was seething with protest, police violence, and counterculture energy. Throughout the U.S., the ground was shaking under America’s youth: the Vietnam War was raging, draft cards were burning, and Nixon’s shadow was lengthening.

Kirk tried a semester at Iowa State but lasted only six weeks before packing up his car and heading back to Chicago. It was there that his identity began to take shape.

For kids his age, the promise of the counterculture — dropping out, pushing back, searching for altered states of consciousness — wasn’t rebellion for rebellion’s sake; it was survival in a society that felt hostile to them. So, in those early Chicago days, Kirk rode the current of acid, concerts, and the constant pull of sound and light.

He first saw the Allman Brothers Band (ABB) almost by accident, wandering into a Chicago club with a fake ID. At first, he and his friends weren’t impressed — the band was too loud to talk over, and they left after an hour. But soon after, he spotted their debut album at a friend’s house, recognized the faces, and dropped the needle. The music hit him hard. He bought two copies the next morning — one to keep at home, and one to carry with him everywhere.

Jai Johanny ‘Jaimoe’ Johanson — the man with the rhythm in his bones, keeping time while the Brothers flew. His jazz-born finesse dovetailed with Butch Trucks’ rock-solid drive. Together they forged the twin-drum thunder that powered the Allman Brothers Band.

By the summer of 1970, he was standing in the crowd at the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival in Byron, Georgia, watching the Allmans headline and realizing they had become the soundtrack of his life.

“I had seen the Allman Brothers a lot in ’70 and ’71, they were my favorite band. I wanted to be good and high when I watched them. But I didn’t take any pics of Duane or Berry, regrettably. Didn’t get one picture after seeing them a lot. I realized about that time I could take a picture or get high, but I couldn’t get high and take pictures. In 1973, I stopped getting so high, and the photography got better.”

And, he found he could make a living at it.

“My dream was to shoot concerts, movies, album covers. Photographers in our co-op had other jobs in the photographic world, most of us actually worked at processing labs. Chicago was a big advertising city and I worked in the black and white lab while my partner worked at a color lab across town. We subsisted on our side photography gigs.”

Kirk sharpened his eye as part of the photo co-op Photos Reserve, made up of music fanatics and concert shooters. It wasn’t a business—just a fellowship of photographers with film canisters in their pockets and sound in their blood.

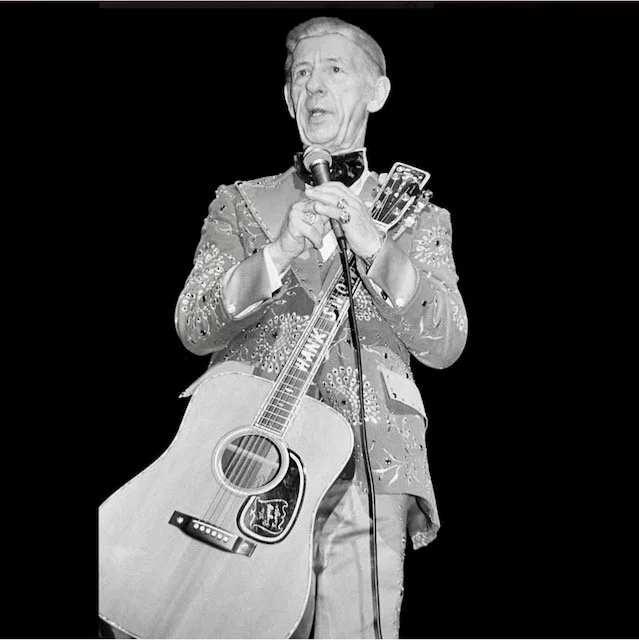

“We all had our specialties. I really liked Blues and old Country, and no one in Chicago cared about shooting Country, so I did that. Another guy liked Alice Cooper and KISS. Somebody else was always chasing jazz.”

They shot what moved them—and learned from each other in the process.

While others might have chased psychedelic color and flower-power spectacle, Kirk was shooting those great Chicago bluesmen in stark, soulful black and white. It wasn’t trendy. It wasn’t flashy. But it was timeless, stripping the frame down to the essentials: hands, sweat, smoke, soul.

Junior Wells. Hound Dog Taylor. Willie Dixon: these performers were architects of American music.

Kirk was capturing a lineage of musical elders, and he photographed them like the legends they already were, even before most of the world caught on. It wasn’t just a stylistic choice. It was reverence.

And here’s the kicker: those photos, taken by a young man still finding his own voice, have become some of the most enduring images of the electric blues era. They’ve been exhibited, printed, and preserved not just in Kirk’s own Gallery West, but in private collections and archives that understand what a gift it is to see legacy in real time.

Back then — and for most of his life — Kirk worked with film. Not the quick snap-and-swipe of today, but the slow art of coaxing images out of light and shadow. It meant carrying rolls of 35mm in his bag, never quite knowing if he’d nailed the shot until much later. In the darkroom, he’d slip those negatives into chemical baths, hang them to dry, then hunch over contact sheets with a loupe pressed to his eye, hunting for the frame that caught lightning. Burning and dodging prints by hand wasn’t just technical work; it was sculpting with light.

He wasn’t only chasing musicians with a camera. Along the way, Kirk worked in small portrait studios, a larger corporation, and three different darkroom labs — places where he mastered the technical side of his craft while composing in the camera and experimenting in the trays. “Photography was my life,” he later said. “Music photography was my passion.”

Black and white became his obsession. “For 20 years, I saw the world in textures and shades of gray,” Kirk told writer Candice Dyer in 2021. “I feel that the b&w prints create a more timeless feel of the image. It also demands that you examine or embrace the subject more intimately, rather than just be dazzled by the colors.”

So, he rarely shot color unless someone was paying him for it. For Kirk, black and white was a way of seeing — truer than the muddy color film of the day, and more revealing of the soul. He studied the work of Larry Clark, whose raw Tulsa project influenced his eye, as well as Jim Marshall and Annie Leibovitz, who embedded musicians in their environments rather than in formal studios. Kirk carried that ethic into his own work: photographs rooted in context, intimacy, and real life.

Every photograph was a commitment: hours in the dark, fingers stained with developer, chasing that one image that told the story the way only film could.

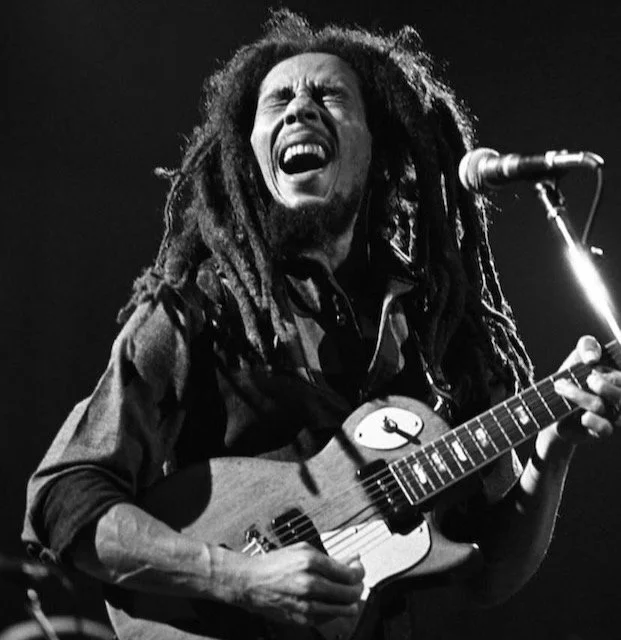

Here’s only a glimpse of the company he kept — artists he began photographing in 1968 and never stopped honoring:

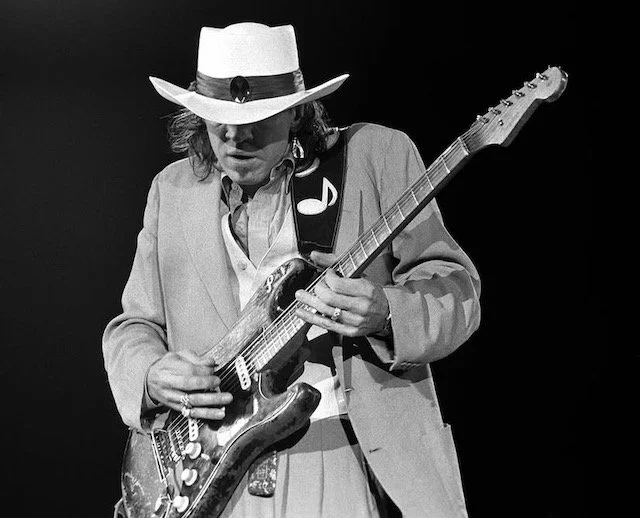

Frank Zappa and The Mothers Of Invention | Etta James | Country Joe And The Fish | Pacific Gas And Electric | The MC5 | Muddy Waters | Tom Waits | Hank Snow | Bob Marley | Albert King | Keith Richards | Albert Collins | Iggy Pop | Bruce Springsteen | Peter Tosh | Sting | Stevie Ray Vaughan | Tammy Wynette | George Jones | Merle Haggard | James Brown | Grateful Dead | Charlie Daniels | Johnny Cash | June Carter Cash | Carl Perkins | Jerry Lee Lewis | Willie Nelson | Delbert McClinton | Son Seals | The Rolling Stones | Otis Redding | Little Richard Ministry | Van Halen | Merle Haggard | The Police | Pat Boone |

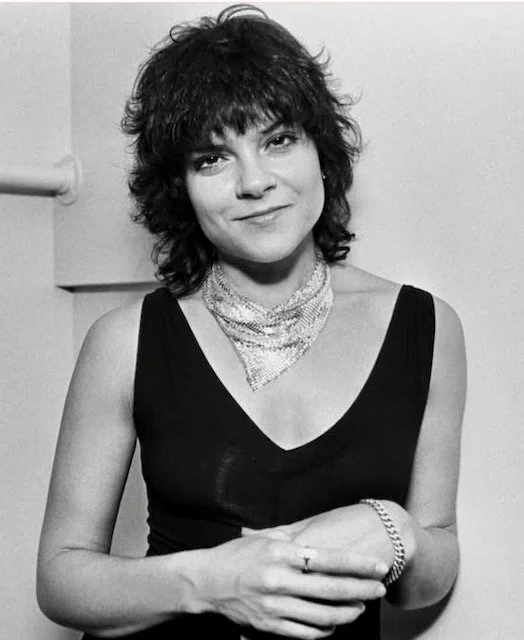

A graceful portrait of Susan Tedeschi by Kirk West, taken in Milwaukee around 2002. West first met Tedeschi on a ‘Blues Cruise’ when she fronted her own band, and their friendship has endured decades — a testament to the way Kirk’s camera work often blossoms into lifelong connection.

The original lineup of the Tedeschi Trucks Band before their debut performance in Savannah, April 2010. From his days traveling with the Allman Brothers Band to documenting new generations like Susan and Derek Trucks, West has remained not only a witness but a friend, keeping ties with the artists he photographs long after the flash fades.

Kirk’s photography has never been confined to the backstage or tour bus. His dream of documenting concerts became real in the late ’70s when he started shooting covers and went on the road with bands, working freelance or for publications like the Chicago Tribune.

Over the years, his work has appeared in major magazines, newspapers, and album liner notes—proof that the gamble to live by his lens paid off. Including his iconic contributions to the ABB’s visual identity; album covers for Seven Turns, Shades of Two Worlds, and An Evening with the Allman Brothers Band. His images have graced magazine covers and record sleeves for artists like Willie Nelson, Delbert McClinton, and Son Seals, and have run in countless publications from local weeklies to national music journals.

Each photo published, each cover printed, was a quiet validation: that the road he’d taken—camera in hand, instinct as compass—was the right one.

In 1973, he started following the ABB with a camera and a purpose, and ultimately freelanced his way into the Brotherhood—first unofficially, then as their tour photographer. By the late ’70s, when the band regrouped for the Enlightened Rogues tour, Kirk’s role expanded through his work with Capricorn Records. Based in Chicago, he became the label’s go-to photographer in the city, shooting not only the Allman Brothers but also the Marshall Tucker Band, the Dixie Dregs, and Sea Level whenever they came through town.

In 1979, he hit the road with the Allmans for the first time, traveling with them through the tours of ’79, ’80, and ’81. He became part of the inner circle, close to the band in a way that transcended freelancing.

Even when the group split again in the early ’80s, Kirk had crossed the threshold into Brotherhood. From that point on, his creative life revolved around the Allman Brothers. Other bands came and went but the ABB became his center of gravity, the bus he always returned to.

Kirk West in Gallery West, repping Howlin’ Wolf with Red Dog at his feet—a living tribute to the ABB roadie and loyal studio sidekick. Photo by DSTO Moore for his Macon Music Project published by Macon Magazine.

Kirk was living what he was chronicling. He slept when the band slept. He endured what they endured. He saw and felt the chaos, camaraderie, and soul of a band born in Southern soil and baptized in grief.

This is what makes Kirk different from the average rock archivist: he never positioned himself outside the story. He was in it all the way. Still is.

In the looser, post-breakup era of the late ’70s, the barriers came down. The venues got smaller. The backstage access got easier. And Kirk, ever the documentarian, slipped right into the frame.

In his North Side Chicago apartment, he built a shrine: more than 1,500 hours of unreleased recordings, videotapes, backstage passes, ticket stubs, belt buckles, and stories too wild to print. It was mostly devotion and a little nostalgia.

That devotion culminated in 1989 with the release of Dreams, a four-disc box set co-produced with Bill Levenson. West curated the tracklist, dug up master tapes from humid Florida garages and Gregg Allman’s closets, and unearthed buried gems like “Drunken Hearted Boy.” He interviewed old sound men, scoured classified ads, and taped more than a thousand hours of rehearsals. Kirk understood that music like this came from the amps—and from the lives behind it.

Dreams was a reclamation. A resurrection. The masterful liner notes, the track selection, including the blistering “You Don’t Love Me/Soul Serenade” tribute to King Curtis—weren’t random choices. They were sacred artifacts, curated by a man who understood their bloodlines.

It was music and bloodline restoration.

“I love music but can’t carry a tune in a bucket,” Kirk laughs. “But I could document it.”

He sure can.

The Gospel of the Archive

In the mid-80s, after the ABB had fractured (again), he began a quiet, obsessive hunt for the music and memories they left behind.

“I spent a couple, three weeks at Dickey’s house helping him build a garage—and copying tapes,” Kirk told interviewer Gary James. “I didn’t take a tape. If you had a tape at your house, I’d unload my recording gear from my car and copy it. I wouldn’t take it away from you.”

The ABB didn’t have a benefactor like the Grateful Dead’s fabled acid millionaire. No one was recording every show with an eye toward legacy. Instead, original sound man Mike Callahan would tape a gig here or there so the band could hear themselves—and hand it to Duane Allman, who often gave it away. Roadies, girlfriends, even Gregg’s Mama’s house held bits of the band’s soul.

“In the spring of ‘97 on Dickey's side porch, we gathered the new line up for some photos & fun. Jack & Oteil fit right in after a couple weeks of rehearsal ... take a few pictures & take the highway... folks were amazed by the new boys & a good summer was ahead for em... Jack would last 2 years & Oteil would be there until the end in 2014... the road went on for a very long time ....

… as always... foto by Kirk West/ Retro Photo Archive.

But in the early 80s, when the band had splintered and the spotlight had dimmed, Kirk was already paying attention. He began work on an early ABB book project with co-writer Joanne Zangrilli, a fellow archivist and editor who shared his passion for documenting the band's story—before it was cool, and before there was any money in it.

The two of them, backed financially by fellow ABB super-fan Ron Currens, spent years digging into the band’s past—conducting interviews with musicians, family members, road crew, and close friends. Kirk even left his job at a Chicago ad agency for four months to go south and dive headfirst into the project. He was collecting stories and building a record. Not just of what the Allman Brothers played, but of who they were.

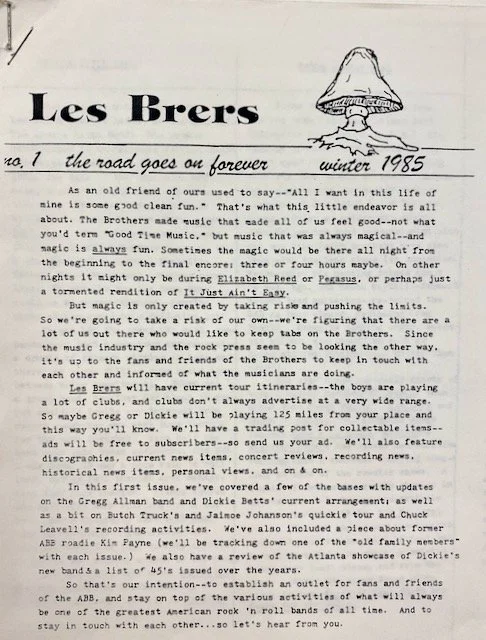

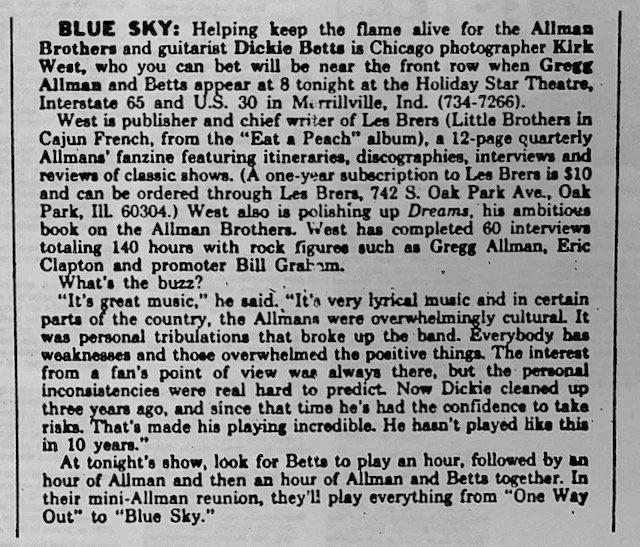

That work laid the foundation for Les Brers, Kirk’s grassroots ABB fan publication that launched with issue #1 in 1985. Part newsletter, part lifeline, Les Brers connected fans across the country and the world through its handwritten notes, tour itineraries, clippings, rare photos, and deep interviews.

As noted in the winter 1988 issue, the book project with Joanne was the reason that issue of the newsletter was delayed—and the reason Kirk made the leap from advertising to full-time documentarian.

Photo: Les Brers #1.

By 1987, his archival work was gaining wider attention. A Blue Sky fanzine article described Les Brers as “a 12-page quarterly featuring itineraries, discographies, interviews, and reviews of classic shows,” and noted that Kirk had compiled more than 140 hours of interviews with figures like Gregg Allman, Eric Clapton, and music promoter Bill Graham. These weren’t just snapshots—they were an oral history in real time. Kirk’s work in preserving the Allmans’ larger legacy helped fans reconnect with their heroes during a time when the band itself was still trying to find its way back.

Those hundreds of hours of raw, unfiltered conversation would go on to become invaluable. Years later, Kirk sold the trove of recordings to author Alan Paul, who used them as the backbone for his book Brothers and Sisters, and publicly credited Kirk for the “precious cargo” no one else had. Not even Kirk had listened to them all.

And wouldn't you love to get your hands on that early biography manuscript by Kirk and Joanne—whatever form it’s in?

As for Les Brers, it didn’t stay just a newsletter. It became a gathering place—first by mail, then in person. That early fan community helped foster something bigger: the Georgia Allman Brothers Band Association, or GABBA. While Kirk may not have been an official founder, there’s no question he helped build the fire that kept the fandom warm.

GABBA grew out of the spirit that Les Brers cultivated—connection, curiosity, and reverence for a band that, at the time, wasn’t even sure it had a future. Kirk’s devotion to preserving the sound and the story gave fans a new way to belong to something deeper than a greatest hits list.

Front pages of Les Brers, the fan-driven newsletter that kept the ABB flame alive. Today, copies of Les Brers and Hittin’ the Note rest in Macon’s Washington Memorial Library Allman Brothers Band Special Collection—alongside photos, albums, news clippings, memorabilia, and Capricorn Records treasures. A must-stop pilgrimage for any true ABB fan.

Kirk helped create a community long before social media or reunion tours made it easy. Back then, you had to dig through clippings, type up real letters, meet up in parking lots, and remember who played the second solo at Watkins Glen. And Kirk remembered. He had the tapes.

By the 1980s, those tapes had become more than souvenirs.

“I spent the ’80s and a good bit of the ’90s tracking down and gathering tapes and creating a tape archive that was pretty extensive,” Kirk told interviewer Gary James.

Much of it was on high-end cassettes and reel-to-reel, later transferred to digital as technology evolved. Every time a new format came along, Kirk upgraded the archive, ensuring the music wouldn’t be lost. And once he joined the band as an employee in 1989, archiving became mission critical: he made sure every single show was taped, sometimes in three or four formats, laying the foundation for what is now the definitive ABB live archive.

Clearly, the early ABB—and even newly formed Capricorn Records—didn’t have an archive plan. But they had Kirk. And before that, they had Willie Perkins, the ABB’s tour manager in the early 70s, who was already collecting memorabilia on the road. Willie even published a book of ABB artifacts years later, crediting Kirk with contributing several rare items and photographs: The Allman Brothers Band Classic Memorabilia 1969-1976, co-authored by Jack Weston and with an introduction by Galadrielle Allman, Duane Allman’s youngest daughter.

Thanks to Kirk’s foresight and relentless work, Les Brers became the connective tissue between the band and its most loyal fans. You could even say it laid the groundwork for Hittin’ the Note, the beloved fan magazine Kirk and Kirsten began publishing while living in The Big House—a kind of living scrapbook of ABB history in real time… and running for 24 years.

Ron Currens, the ABB super-fan, researcher, and early backer, believed in Kirk’s work and went on to play a major role in shaping Hittin’ the Note. Like Kirk, Ron was more than a fan who simply wrote for the magazine and edited it at times—he was a documentarian in his own right, ensuring the band’s story was preserved with care, curiosity, and depth. Together, Kirk and Ron helped create a grassroots archive long before the Big House Museum or official retrospectives existed.

With all his writing, photography, and publishing, Kirk became much more than just a chronicler of Southern Rock—he became a co-architect of its legacy.

“The Boys waitin’ on the bus... Burt Reynolds ranch... Jupiter, Florida... Spring of ‘94 during the recording of Where it All Begins... the ranch’s film settings provided lots of cool locations for still photos.... a great couple days of group shots.”

… as always... foto by Kirk West/Retro Photo Archive.

Kirk’s Other Camera

Kirk had that archivist’s eye long before he ever called himself one. He started out collecting hot rods and ended up collecting history. First it was model cars, then cameras and tour laminates, set lists and fan newsletters, bootlegs and backstage passes.

By the time the ABB re-formed in 1989, Kirk was already building what would become the most comprehensive ABB archive in existence.

He was known for his camera lens, but he had another one—a quieter, more internal way of documenting the world. He was always watching… gathering… remembering. While the world looked at the spotlight, Kirk was building the archive in the shadows.

Kirk West and Dickey Betts at Woodstock ’94 — making memories as vibrant as their shirts.

(Photographer unknown, via kirkwestfotos Instagram.)

Kirk was saving scraps from day one — ticket stubs, contact sheets, tour notes, stories half-told and half-lost. He documented the road in real time—through his camera, through his Les Brers and Hittin’ the Note tour reports, and through the anthology projects he helped spearhead.

If there was a detail to remember, Kirk wrote it down. If there was a moment to capture, he already had it on film.

He wasn’t doing it for credit or applause. He was doing it because he understood that memory fades, and someone has to keep the receipts.

Not everyone saw Kirk’s vision at the time. And not everyone understood what he was building while he was building it. That’s often the way it is with people who don’t shout. Kirk never led with ego. He wasn’t the loudest voice in the room. Still isn’t. But the loudest voices aren’t always the ones saying the most.

When the idea of a Big House Museum came to life, Kirk made a monumental donation—his personal collection of ABB memorabilia, valued in the millions, became the seed for what fans now walk through today. He didn’t give everything away, but what he did share laid the groundwork for preserving the band’s legacy for generations.

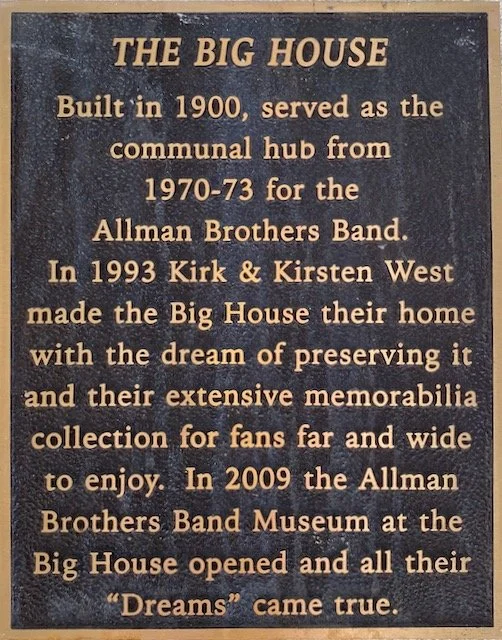

The Big House Museum on Vineville Avenue — the heart of the Allman Brothers Band’s story and a place Kirk & Kirsten West helped bring to life as renovators, archivists, and historians.

Kirk’s donation to the Big House wasn’t just a handoff of memorabilia. It was the transfer of a lived archive, a gift of decades’ worth of artifacts and context. It was the seed that helped the museum grow into what it is today.

Kirsten was there for all of it—cataloging, scanning, organizing the chaos. Cooking for guests like Colonel Bruce Hampton and Bonnie Bramlett in their home on Vineville Avenue. She helped turn that home into the headquarters for ABB history. She understood what Kirk was doing long before most others.

It’s not a stretch to say that without Kirk, the ABB might have left behind music but no memory. He is the one who remembers. He and Kirsten safely tucked away the receipts.

The value of an archive often isn’t clear until someone else needs to tell the story, and Kirk was building what he knew mattered—to fans, to future scholars, to music lovers who hadn’t even been born yet.

After all, quiet doesn't mean absent, and humble doesn’t mean small. In Kirk’s case, it meant deliberate, devoted, deep.

Big Adventure at The Big House

But let’s back up to where his story with Macon began.

In 1993, Kirk and Kirsten bought the Big House, the original communal home of the ABB, and moved south from Chicago. Kirsten’s idea to turn the house into a rock-and-roll Bed & Breakfast became their shared dream.

That plan got tangled in fire codes and city red tape. They weren’t about to shell out more money to add a fire escape or industrial kitchen.

“We got around the codes by not charging folks,” Kirk says. “We had a gift box and folks would pay what they thought it was worth to stay at the house.”

So they had pivoted: instead of a business, they created a destination.

“We had put the notion out there,” Kirk says, “and were on CNN and the Travel network. That early attention created a destination and we had to evolve with it.”

The fans started flowing toward Macon.

Long before the museum sign went up, the Big House was already a place where Macon’s past and future collided — where Kirk and Kirsten learned just how fiercely this city holds on to its ghosts and guitars.

Kirsten ran the house while Kirk stayed on the road with the ABB. She’d renovated homes in other towns, so managing a crumbling Macon landmark came naturally.

Their vision extended beyond preservation—it was about participation. They gathered a tribe of young artists, trained them in photography, design, and screen printing, and built a groundswell of culture around the band’s legacy.

More than 25,000 visitors knocked on the doors of the Big House while they lived there.

Kirk started Hittin’ the Note newsletter for ABB fans and Kirsten managed it, every detail, down to addressing and stamping envelopes, until it grew into a full-color, glossy magazine.

Inside The Big House Museum, every wall and display hums with the Allman Brothers Band’s history — from gold records, tour posters, and well-traveled stage gear to the instruments and images that keep their spirit alive. Much of this preservation owes its soul to Kirk West’s years as the band’s archivist and to Kirsten West’s dedication to keeping the house intact for fans to walk through these doors.

Two of the rooms housed all of Kirk’s ABB memorabilia, displayed for visitors to view. The Big House wasn’t just stucco and ephemera. It was the emotional and spiritual core of the Brotherhood, brought back to life, and it became an official museum in 2009, born out of a well-funded foundation, sweat, and stubborn love.

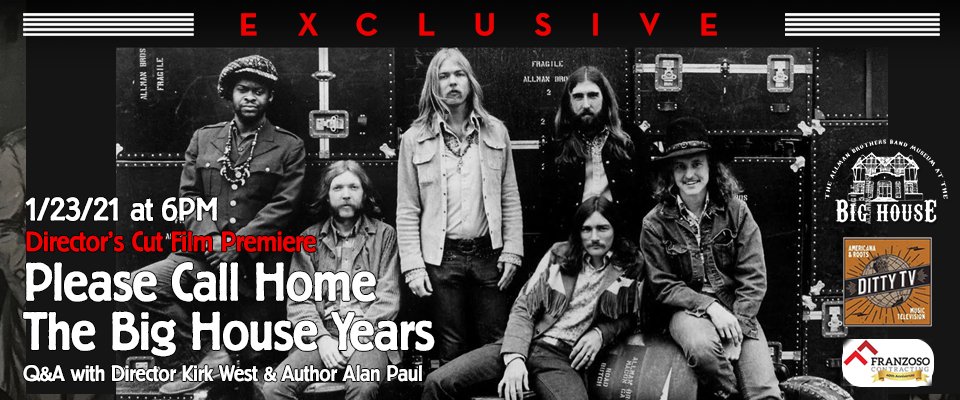

Kirk had released the documentary Please Call Home to raise funds for the Allman Brothers Foundation.

“I made Please call Home in 2005, intending it as a 15-minute infomercial, but we had such great footage of members, wives, children, etc., we extended it to 90 minutes. We could only talk about the years the band lived there, which was 1970 to 1973, when At Fillmore East and Brothers & Sisters were recorded. Gregg wrote the song Please Call Home about the Big house, so we had to play it in the documentary. It’s a great little film.”

Please Call Home is available for purchase at Gallery West, and it really is a great little film!

Kirk and Kirsten lived in The Big House for 14 years before selling it to the Allman Brothers Foundation.

Please Call Home: The Big House Years

Directed by Kirk West, this film is a backstage pass to the early days of the Allman Brothers Band—shot with heart and the eye of a brother who was there. Featuring Linda Oakley’s powerful perspective, it’s as much about the family as the fame. Premiered in 2021 and still raising goosebumps. Available now at Gallery West.

On the Road

Kirk spent twenty years touring with the ABB—a stretch of time most folks wouldn't survive, much less thrive in. Life on the road is grueling: moving equipment to a new venue every other day, keeping the band and crew fed, lodged, on time, and ready to perform. There are moments of glory, sure—roaring crowds and encores and backstage magic—but also long hauls, broken guitars, and more stress than sleep.

Four weeks on the road and then two weeks at home, over and over again.

Kirk learned to endure it with a sense of humor. And he learned not to take himself too seriously. At 30, he wore the road well and brought with him a creative, offbeat energy—and a knack for solving problems with flair. He quickly outgrew the title of Assistant Tour Manager.

“I didn’t feel like I was an assistant anything. The itinerary listed our titles and I thought, ‘You know, I don’t want to be assistant .’ So I told the tour manager, ‘How about we come up with a different title because I do a lot more stuff than just assistant. I pull rabbits out of hats and make assholes disappear. What about Tour Magician?’”

The title stuck for a while, until roadie and fellow-character Red Dog gave him a new one: Tour Mystic.

“I thought that was funny,” Kirk says with a grin.

Titles, after all, tell stories. They hint at roles within the traveling circus of a touring band. Kirk remembers a summer when the ABB hit the road with the Grateful Dead—another band known for its free-form philosophy and eclectic entourage. One of the Dead’s crew members was having liver issues, so they brought along a man named Doctor Phil—not the TV personality, but a real San Francisco mystic of sorts.

“That summer,” Kirk says, “my job title became Chinese Herbalist. It was an inside joke. One day before a show, Doctor Phil came to me wanting to talk about herbs. Actually, I was the guy who received the pot and then spread it to the band and crew. Weed was the only herb I handled.”

That’s how he got close to the band in the first place.

“Because I had pockets full of reefer,” Kirk laughs. “You get to know a lot of bands that way.”

It was a half-joke, and also mostly true.

Beneath the humor was a reality familiar to many who lived on the road in that era: a touring life greased by booze, marijuana, and whatever else kept the engines running. The grind was constant; escape came in many forms.

It’s no secret that life on tour could wear a body down. In those days, the antidotes were often liquid or smokable, or sexual—whatever dulled the exhaustion, broke the boredom, or took the edge off the pressure. Kirk doesn’t glorify that part of the job, but he doesn’t deny it either. He was there, helping hold it all together while the wheels kept turning and everyone did what they had to do to get to the next gig.

Gallery West

“I was tour manager of the ABB throughout the 90s and early 2000s,” Kirk says. “In 2010, I retired from the road and Kirsten had the idea to open Gallery West.”

They launched Gallery West in 2015 on 3rd Street in downtown Macon—Kirk’s photo archive reimagined by Kirsten as a community hub. Well, at first she had envisioned a pop-up gallery lasting one holiday season, but like most things Kirk and Kirsten start, they made a success of it and celebrated 10 years this past February!

Celebrating 10 years of Kirsten hosting visitors at Gallery West — where Kirk West’s iconic images share the walls with visiting artists and photographers, live music fills the air, and Macon’s creative community comes to hang out. Photo via Gallery West Facebook, photographer unknown.

“I just kept saying yes to life,” Kirk says, thinking back on Kirsten’s visions, and a lifetime of unexpected chances. “Every time a door cracked open, I said, ‘Sure, I’ll try that.’ I never did learn how to say no—and maybe that’s the whole secret.”

And because he kept saying yes, a whole creative community bloomed around him.

Turns out, “yes” can build a gallery, a scene, a life—and Kirk said “yes” like he meant it.

Then he spent three years scanning 60,000 negatives, prepping prints, and quietly cursing every speck of dust that tried to sneak into his legacy.

Gallery West became his next great act: a space to show and sell his prints, to share his memories in tangible form, and to keep the circle unbroken.

That circle was always rooted in Macon — a town that gave Kirk and Kirsten a reason to stay put after so many miles on the road. If Chicago gave him his lens, Macon gave him his frame.

And the gallery displayed his life’s photographic work (or at least a portion of it).

He’s since sold the rights to his earlier works, a quiet closing of a chapter. But the space remains active. Kirsten still hosts, for now. She’s looking to retire from her manager duties at the gallery in early 2026. Local artists still exhibit and gather, and plan to take over the gallery’s management when Kirsten retires to her dream home in Macon’s Shirley Hills neighborhood. Kirk still walks in, slower these day by his own admission, but still sharp-eyed.

Gallery West continues to serve as a vital intersection of music and visual art—just like Kirk himself. The gallery doesn’t just showcase Kirk’s photographic legacy; it also champions contemporary Southern artists and musicians, providing a space where creativity is honored in all its forms.

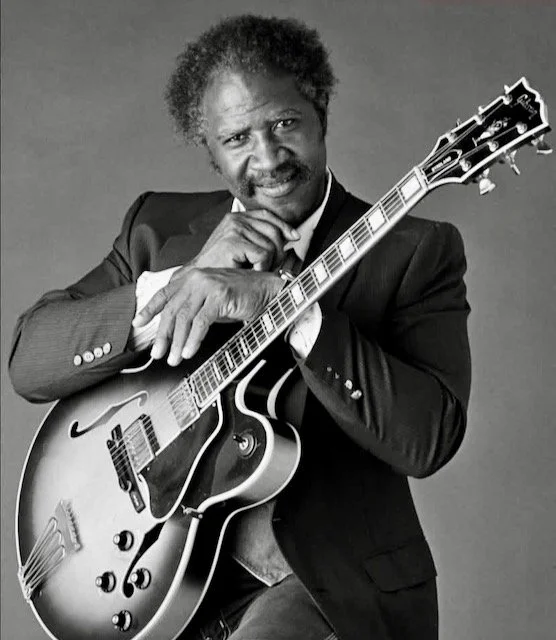

Local legends like R&B guitarist Robert Lee Coleman are invited to perform there, and that same spirit of recognition carried through when Mr. Coleman was awarded the Medal of Freedom from the Tubman Museum on August 15, 2025, along with William Bell, a Stax Records icon.

Kirk’s camera has long focused on artists worth remembering—and now, through Gallery West, his lens becomes a platform for spotlighting others… such as local photographers Bill Brookins and DSTO Moore, local visual artists Johnny Mo and Kevin Lewis, and local musical artists like Mr. Coleman... plus many more.

And Kirk keeps the fire lit in other ways — his voice, smooth and grounded, now broadcast every Monday evening on Macon’s 100.9 The Creek in a radio show called Into the Mystic. Starting each show with his signature “Howdy Boys & Girls,” he records at Capricorn Studios, where Southern Rock was minted, sitting at a console, calling up old records and new favorites, telling stories with the weight of someone who was there.

Into the Mystic is more than a playlist—it’s a musical memoir. Kirk shares obscurities and personal tributes, lessons wrapped in vinyl and memory. He doesn’t sugar-coat his past either.

By 1975, he was running on fumes — heroin in his veins, packs of Camels in his lungs. Those years of addiction weren’t only lost to drugs. Kirk had drifted in and out of Chicago through the ’70s, restless and reckless, eventually landing in Florida facing serious criminal charges.

Then the ABB’s Win, Lose or Draw had dropped, and “Can’t Lose What You Never Had” cut straight through Kirk’s haze. Instead of folding into his addiction, he fought back.

“The Allmans gave me hope when I didn’t have any,” he later said.

It was a turning point: he cleaned up, quit being, as he put it, “a deadbeat,” and rebuilt his life in sobriety. By the late ’70s, he was back in Chicago, more focused than ever, with a new set of cameras and a renewed sense of purpose.

The ABB’s music had saved him and he was saving their music right back. Now he tells his stories, raw and unvarnished, for our benefit. His genuine reflections on those times come out in his on-air remembrances, the only “selfie” we’ll ever see from Kirk, because he’s never taken an actual selfie. Proof that he’s more interested in what the music shows us than what a camera shows of him.

“the show is really just me playin my albums & tellin the occasional tale.... but its mostly a fine way to spend an hour or so... hope ya give it listen.”

Kirk on Instagram, May 1, 2023.

“I have fun with my radio show,” Kirks says. “I pull the records. I cue up the songs. I tell the stories. It doesn’t take much energy, but I still have to have my mind right.”

You can hear that sensibility on full display in his Creek radio show; it’s a playlist and a personal archive in motion.

Always with the motion, this guy.

Kirk did sit still long enough to curate and publish his photos into two books:

• Les Brers: Kirk West’s Photographic Journey with the Brothers — This oversized, four-decade-spanning coffee-table chronicle features nearly 1,000 photographs— gritty backstage scenes, candids offstage, and arena moments—of the ABB, their solo projects, and side outfits including Gov’t Mule. Interwoven with Kirk’s own reflections, and a foreword by Warren Haynes, it’s not just a visual feast but a personal narrative of Southern Rock history.

• The Blues in Black and White The Photography of Kirk West — A passionate visual homage to the heart of the blues: a photography book that brings alive the artists, venues, and culture of the Chicago blues scene and beyond—with Kirk’s lens as our guide.

Kirsten West, Godmother of Southern Rock, stands inside Gallery West, co-founded with her husband, photographer Kirk West. Here she holds Les Brers: Kirk West’s Photographic Journey with The Brothers, a visual chronicle of the ABB. Through her stewardship of the gallery, the Big House, and decades of behind-the-scenes dedication, Kirsten has helped preserve not only Kirk’s vast archive but also the living spirit of Macon’s music legacy.

Photo by Little Guide Macon.

Onward Through the Fog, My Friends

Even now, Kirk’s still telling stories. He just added new platforms.

On Instagram and Facebook (kirkwestfotos), he’s been posting from a “little search thru the forgotten folders”—photos pulled from dusty boxes and old hard drives, each one paired with a memory, a vibe, a scrap of poetry. It’s a digital scrapbook for the faithful, with captions that read like roadside haikus from the golden age of Southern Rock.

It’s the same storytelling voice he brings to his Creek radio show: poetic, sardonic, reverent, and irreverent. On the air, Kirk shares his personal soundtrack—records pulled by hand, stories told in his soothing voice. On social media, we get the visuals: a time-traveling tour book, one caption at a time, often sounding like a song itself.

Together, it’s a living archive in motion. The music, the memories, the man.

And that’s because, for Kirk, the shutter click was only the start of a friendship. For years, he kept up with the people he photographed — calling, visiting, sometimes hopping in the car to catch a show or just sit in their kitchens (or have them sit in his). He delighted in their company, laughed at their stories, and shared his own brand of dry humor right back.

Many of those bonds lasted for decades, whether with the Chicago blues legends he cut his teeth photographing or with newer friends like Susan Tedeschi, who reminded him that she’s known Kirk and Kirsten longer than she’s known Derek Trucks. Or with Mama Louise Hudson, the woman and the legend who fed the ABB and other Southern Rockers at H&H Restaurant, along with her partner Mama Inez Hill, both now gone, but still loved to pieces. And H&H, now with Tangie Myers as general manager, is still serving up their good home cooking with good cheer.

These weren’t ordinary friendships. Kirk somehow made space in his life for the famous and the everyday alike, and he treated them all the same. It’s part of why his social media posts sparkle with so much affection — little flashes of humor, inside jokes, and memories only a true friend could share.

He may have slowed down in visiting with friends in recent years, but his archive proves it: Kirk wasn’t just the photographer on the scene; he was the photographer who dug in for life. He and Kirsten became famous in their own right, yet never lost the kindness and humility that made people want to open their doors, their dressing rooms, and their lives to them in the first place.

“I miss this view soooooo much… ‘you want more gravy on this Darlin?’... wishin we all had more of this... the H&H is still the greatest but we all miss our Momma Louise & her love for her 'children'... go get you some...

"Momma Louise at our house some years back... she always loved to be eating Kirsten's cookin... said she understood why I didn't eat at the H&H more often. Happy heavenly birthday Momma."

…as always… foto by Kirk West/Retro Photo Archive.

Kirk’s Soundtrack

Kirk spent his life capturing music, supporting it, preserving it—but what about the songs that hold him?

When asked about his all-time favorite performer, Kirk doesn’t hesitate: Tom Waits. Gravel-voiced, poetic, and just a little wild, Waits is a storyteller as much as a singer—a perfect match for a man like Kirk who’s always been drawn to what’s raw, real, and a little left of center.

“Tom Waits.... 1978.... a dark corner of Chicago.... where smoke gets in your eyes.... ”

… foto by Kirk West/ Retro Photo Archive.

Waits, Kirk says, was the first artist to treat him like an artist. They collaborated on a series of striking, stylized photos—each one staged by Kirk, with Waits fully game for whatever concept Kirk threw out. That trust paid off in images that still stand out today. And for a creative soul like Kirk—especially one with a poet’s heart—being recognized as an artist by another artist meant everything.

That kind of creative kinship doesn’t come around often, but when it does, it leaves a mark. And it’s not the only time music cracked something open in Kirk. Before the cameras, before the tour buses and museum walls, there was that moment that changed everything: Paul Butterfield’s East/West record, opening him up to a hunger for sound, soul, and stories told better with music than words alone. Since then, Kirk’s personal soundtrack has stretched wide.

And then there’s the deeply personal:

“‘Have a Little Faith in Me,’ by John Hiatt—that was played at my wedding to Kirsten in 1991.” They were married in Buddy Guy’s Checkerboard Lounge blues club on 43rd Street in Chicago with music performed by bluesman Junior Wells himself.

Kirk had placed his first-ever classified ad and Kirsten had answered — her first time responding to one. Within thirty minutes of meeting, he knew he wanted to spend the rest of his life with her. For Kirsten, life before Kirk had been plush but vacuous; with him, it became vivid and real. Beneath the long sleeves he wore on their first date to hide his tattoos, his arms were already becoming a canvas — another extension of his art.

Kirk didn’t get his first tattoo until he was 40, and of course it was the Allman mushroom. “The ABB has this voodoo thing about no one but Lyle [Tuttle] can do the mushroom,” Kirk explained to Tom Gunn of Tattoos magazine, “so I waited six years till we could hook up.”

From there he sought out the best in the business — Fat Kat, Bob Oslin, Roy Boy — each one adding another brushstroke to the story of his life.

For Kirk, tattoos weren’t rebellion or decoration. They were expression — the same drive that fueled his photography, his newsletter publishing, his record producing, his book compilations laced with stories, his radio show, his documentary, and even the photos and reflections he shares on social media to this very day.

Art wasn’t something Kirk did; it was how he lived, written on negatives, on paper, on vinyl, on airwaves — and on his own skin.

The tattoos, the photos, the records, the words—they all tell stories. But Kirk’s richest stories came not from the things he collected, but from people, like Kirsten, and the many bluesmen who became friends for life.

He’s not just a collector of old friends and records. He’s a sharer of songs, especially on his radio show, but in other ways, too. Even as he helped shape the story of Southern Rock, his own musical tastes ran deeper, wider, and more soul-bending than any one genre could contain.

And like his photography, his approach to music is honest and discerning:

“People say to me, ‘Kirk, you never take a bad picture.’ And I say, ‘No, I do take bad pictures—I just don’t show them to you.’”

Same goes for the songs he shares on Into the Mystic. He doesn’t just collect—he curates. What you see, what you hear, is what he’s chosen to keep. And that, too, is an art.

Hank Snow in rhinestone splendor, Marty Robbins with that trademark steely gaze, and Johnny Cash sharing a backstage laugh with Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis. These moments exist because Kirk West was there, preserving the magic for the rest of us.

Macon owes the Wests a quiet debt for the lasting legacy they’ve created. Some debts can’t be repaid, just recognized, honored, and carried forward with gratitude. That’s the kind of legacy Kirk and Kirsten have given Macon—not transactional, but transformational.

Kirk and Kirsten are still here. Still showing up. Still part of the soul of Macon’s creative life. The Gallery West door still swings wide, though someone else will soon carry the load of selling Kirk’s prints—but the couple remains rooted.

These days, Kirk shows up at Gallery West mostly on First Fridays, when downtown businesses stay open, show off, and invite folks in for snacks, drinks, and discovery. Not one to make a fuss— Kirk just eases in to Gallery West, calm and soft-spoken, ready to talk if you’re curious and quiet if you’re not.

It’s a rare kind of presence, the kind you don’t fully appreciate until it starts to slip away. Kirk and Kirsten hint at stepping back and winding down as the year comes to a close. When that happens, the chance to stand beside him and hear the story behind a photo—from a moody blues club in Chicago or a sun-soaked Southern stage—might be gone.

If you’ve ever thought about stopping by downtown Macon and specifically Gallery West, now’s the time. Gallery West still carries that spark and lived-in magic. While the walls will always hold Kirk’s work, there’s something unforgettable about hearing the stories straight from the man who lived them… because some stories deserve to be heard while the storyteller’s still in the room.

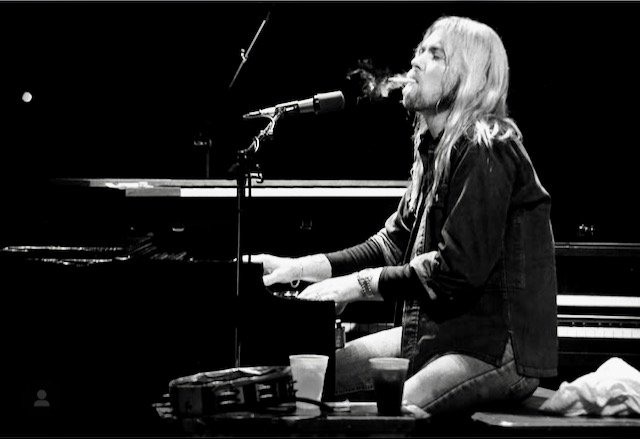

“GA smoking hot at Alpine Valley, Wisc... sometimes Gregg was so easy to shoot.. he was just so fkin cool... this was in July of 1980 and the band was working all the time and bringing in big crowds & my access to the band had become total.. I had the run of the place... just don't unplug anything... but go where ya need to go to get the shot... so I did.... and as always...

... foto by Kirk West/ Retro Photo Archive

...pulling around the corner coming into Sturgis during August of 1990, Gregg & crew riding from Rapid City on a day off ... a tattoo artist from Indiana named Roy Boy hooked GA up with a springer softail for a ride to Sturgis & back... I grabbed a ride along in a mini van with the side door strapped open & I shot the whole trip leaning & focusing & hoping I didn't fall out along the way... Gregg's current wife Danielle was riding on back... as always ...

... foto by Kirk West/ Retro Photo Archive

No Van Morrison Just Yet

Kirk’s been feeling poorly lately, though. Covid hit him hard in 2020— he grew so sick he thought he might not make it. He and Kirsten had both caught the virus in March 2020, after traveling to New York City to photograph what would be the ABB’s final big show.

“We were in a room with 18,000 people,” Kirk recalled to 13WMAZ TV in Macon. “Nobody knew at that time just how much of a hot seat New York City was. This concert was on Tuesday, and on Wednesday morning, they started canceling everything.”

It was a bitter twist of fate: after a lifetime spent capturing the Allmans, it was one last ABB concert — and the stealthy spread of a pandemic — that nearly took him down. Back then, after his harrowing illness, Kirk encouraged people to take the virus seriously.

“I want Van Morrison’s ‘Into the Mystic’ played at my funeral,” he tells me now, maybe a thought lingering from his Covid trauma.

While his body says to pace himself, his mind—his soul—is still in the game.

So no Van Morrison for Kirk just yet.

Not while he’s still spinning the vinyl that shaped his soul, still walking these Macon streets in his Allman Brothers t-shirt—the same town that’s held him and given him a place to keep the music alive.

Kirk lived inside the music as he archived it. And he’s still keeping the flame red hot, shining like a beacon that draws folks from all over the world to Macon, to Gallery West.

And the music? Just like his stories, it still sounds better when Kirk’s around.

Why Kirk is Held Here

Kirk West is Held Here because some people come to Macon chasing the echoes of music history — but Kirk came to make history and keep those echoes alive. He photographed legends while living alongside them, made a home inside their story, and then gave that home back to the rest of us.

He witnessed the music, preserved what might have been forgotten, and knew what to keep. And then he kept it for all of us.

In 2023, Kirk’s decades of work preserving and shaping music history were honored with his induction into the Iowa Rock ‘n Roll Music Association Hall of Fame—bringing the journey full circle for a small-town Iowa boy who once dreamed of the open road.

“Get ready to dive into the vibrant world of rock history with Kirk West, the legendary ‘Tour Mystic’ of the Allman Brothers Band! With over 20 years spent as a key figure in the music scene, Kirk West's contributions are unmatched. From his role as the founder of Hittin’ the Note magazine to his work as the official archivist for the Allman Brothers Band, he has left an indelible mark on the rock music landscape.”

Iowa Rock ‘n Roll Music Association.

Kirk is a reminder that what’s worth saving is worth sharing — an archivist and storyteller who never hid behind the camera but leaned all the way in, letting Macon hold him. The Big House, the gallery, the radio show, social media micro-essays — they’re all testaments to a legacy built with heart, with hustle, and, just as importantly, with Kirsten by his side.

Kirk & Kirsten: Two Halves of a Whole +

There’s something rare and quietly extraordinary about the way Kirk and Kirsten West move through the world together. Their partnership isn’t loud or performative—it’s steady and intentional. They’ve built not just projects and legacies, but a kind of space for each other to grow, to take risks, to be fully themselves. He never clipped her wings. She never dimmed his fire. And vice versa. If anything, they lit each other up.

Over the years, they’ve created room—for the work, yes, but also for ambition, for independence, for the late nights and rabbit holes and obsessive sorting and dreaming that creative lives demand. That kind of support isn’t flashy. It’s not always easy. But it’s the reason they’ve lasted—and the reason their work has, too.

They consult one another and trust one another. That trust has shaped everything they’ve built. A museum. A gallery. A community. A shared life rooted in respect and a fierce kind of freedom. Theirs’ is the kind of union that doesn’t happen often. And for those lucky enough to witness it, it’s clear: the real magic isn’t just in the archives. It’s in the way they keep showing up for each other, and for Macon.

Select quotes and stories in this piece are from my interviews with Kirk in November 2024 and August 2025, and also taken from a 2000s-era interview with Kirk conducted by Gary James of classicbands.com, and a 2007 James Calemine/Swampland interview, both used here with respect.

Next up: Kirsten West—the Godmother of Southern Rock—who helped turn Macon into a music mecca. From reviving the Big House to launching Gallery West and steering the Capitol Theatre, her solid vision makes Macon hum with history and heart.

About the Author

Cindi Brown is a Georgia-born writer, porch-sitter, and teller of truths — even the ones her Mama once pinched her for saying out loud. She runs Porchlight Press from her 1895 house with creaking floorboards and an open door for stories with soul. When she’s not scribbling about Southern music, small towns, stray cats, places she loves, and the wild gospel that hums in red clay soil, you’ll find her out listening for the next thing worth saying.