Kirsten West: Godmother of Southern Rock

Held Here is a profile series highlighting the artists, archivists, entrepreneurs, and visionaries who have shaped Macon’s cultural identity. Each subject is someone who planted roots and, through their work and presence, have helped preserve the city’s creative spirit for the next generation.

This profile features Kirsten West, arts advocate, entrepreneur, and co-founder of The Allman Brothers Band Museum at The Big House. As a driving force behind Hittin’ the Note magazine and the ever-welcoming Gallery West, Kirsten has spent decades keeping Southern Rock’s legacy intact and alive. But her reach extends further; she has also helped shape Macon’s cultural renaissance, reviving historic spaces like the Capitol Theatre and championing a creative community that stretches well beyond music.

Midwestern Girl Breaks Out

Minnesota gave her a beginning, but music gave Kirsten West a home—at first a boundless house with no walls, and later a home with walls strong enough to hold its music and its ghosts.

Like so many young people in the late 60s, Kirsten headed west, landing in Los Angeles just in time to catch the coast’s cultural wildfire. With music as both her place and her passion, she paid attention—remembering who played what, and how it made her feel.

After Hollywood, she moved to Canada, then Hartford, Connecticut, where she built a successful career in the insurance industry, rising to become a vice president of a multinational firm.

When she met Kirk West in 1991, she couldn’t name a single Allman Brother besides Gregg. As the Allman Brothers Band (ABB) Road Manager, Kirk didn’t even mind. He was just impressed that Kirsten knew the names of the great bluesmen, the ones he’d been capturing on film since 1968.

Kirsten and Kirk married within months of meeting and two years later moved from Chicago to Macon, Georgia. Along with Kirk, Kirsten saved stories and, lucky for Macon, she has stayed.

Over the decades, she asked for so little… while giving so much… to both the ABB legacy and the city. Kirsten has chronicled the band’s journey, funded it, renovated it, and kept it from vanishing. Not because she craved credit or fame, but because she believed it mattered.

In the Southern Rock world known for its Brotherhood, Kirsten formed her own legacy as a woman with business experience, sound visions, and the pluck to follow her instincts every time, regretting nothing.

Now, she has much to celebrate… and we celebrate with her.

Kirsten West is the quiet force behind some of Macon’s loudest legacies. From restoring the Big House to publishing Hittin’ the Note, she turned history and heart into a home for Southern rock. Her courage, curiosity, and that firecracker red dress say it all — Kirsten’s been making room for music, art, and meaning in Macon for decades.

Photo by DSTO Moore (thanks, DSTO!)

Hippie at Heart, Executive in Heels

Kirsten came of age in Minnesota, where the rhythms on the airwaves became her home and then her compass, pointing her toward a life that would refuse to stay small. She was adventurous, and not just in the usual sense — she was spiritually curious, too, believing that energy and intuition can guide a person if they truly listen.

“I’ve had multiple incarnations in one lifetime,” Kirsten says, not exaggerating. Through them all, she’s been a committed feminist—living her belief in her own power and carving out space for other women to push past the roles society tries to hand them.

Kirsten tried college while drifting toward the expected, but the pull of something bigger was too strong. By the late 1960s, California was calling her… to a place where the counterculture was in full bloom, wild and unbuttoned, and music spilled out of every doorway.

On a whim — and in the company of an equally adventurous girlfriend — Kirsten packed her curiosity and nerve and headed for Hollywood, just as the city was tilting into its most electric years.

“We were definitely hippies,” she says, laughing at the memory.

When Kirsten landed in Hollywood in 1968, she stepped into a city that glittered with promise while it quaked with change. By day she was working with a prominent interior designer in Beverly Hills, helping stage the sleek modern interiors of a changing world. By night, she was chasing live music in smoky clubs, watching artists test the edges of what sound could do. She didn’t need to be on stage to feel it — music was her home and the rhythm was already in her bones.

Hollywood, 1968–1971

In Los Angeles, Kirsten worked with C. Tony Pereira, a mid-century interior designer known for his work on the restaurant/lounge at Palm Springs’ Ocotillo Lodge in the 1950s and his custom interior decor work in L.A., including being featured in the 1959 Parade of Homes showcase. He collaborated on projects tied to the architectural firm Palmer & Krisel, placing him squarely in the modernist design world of Rat-Pack-era Southern California — the kind of scene where style and glamour met opportunity.

Kirsten remembers that Pereira designed celebrity homes for folks like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, and she worked with him on houses in Beverly Glen, where she chose wallpaper, fabrics, art, flooring, and furniture that matched each house’s unique decor theme — creating spaces that reflected her artist’s eye, which she had honed in art school.

After her design work in Beverly Glen, Kirsten took an unexpected turn. Working in Pacific Bell’s political-campaign division, she laid out phone banks like floor plans — rows of handsets, taped extension numbers, volunteer sign-in sheets — turning a tangle of cords into a room that worked. It was “old school” in the best sense, and choreography more than furniture: tables, lines, power drops, call sheets, and just enough space for a weary volunteer to lean on an elbow between dials. Far from her wallpaper-and-curtains world, the job taught her how to envision space with people in motion, and how a room set-up can shape work and productivity.

Outside those well-designed glass-walled homes and campaign offices, Hollywood was alive with music and Kirsten would have felt it. The canyons — Laurel, Topanga, Beechwood, Nichols — became creative havens where neighbors happened to be Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa, or Crosby, Stills & Nash. Carole King settled into a piano in Laurel, Jim Morrison prowled the streets, Neil Young and Graham Nash traded riffs from porch to porch. Out of this heady mix came songs that defined an era — Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi”, King’s “It’s Too Late”, The Doors’ “Love Street”, and CSN’s “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” The canyon crowd was weaving together folk harmonies, psychedelic textures, and domestic bohemia that spoke to young people like Kirsten, who were seeking freedom and adventure.

Meanwhile, down in the Valley, producers like Phil Spector were building the so-called Wall of Sound — lavish, layered arrangements that turned pop singles into symphonies, from the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” to the Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” the Crystals’ “Then He Kissed Me,” and Ike & Tina Turner’s “River Deep – Mountain High.”

Where those canyon songs felt like friends trading riffs on porches, the Wall was dense and orchestrated, crafted for radio airplay and teenage transistor radios. Both sounds were shaping the era, but they pulled from opposite instincts—one intimate and organic, the other grand and overwhelming.

Living in Hollywood at the time, Kirsten would have absorbed the city’s split personality: the cozy circle of singer-songwriters that made the neighborhood feel like family, and the booming spectacle pouring out of every radio. It would have given her an early sense of how art can live both in community and in commerce, an awareness she would later carry into her own work and the spaces she’d build in Macon.

Southerners were also woven into that California scene; musicians out of Gainesville, Florida, like Stephen Stills and Bernie Leadon of the Eagles carried swamp-bred sensibilities west, shaping the canyon sound. Back in Jacksonville, the city was already churning with its own future legends — Lynyrd Skynyrd, .38 Special, Molly Hatchet — a wave of Southern rock waiting to crest. They had all been inspired to take up an instrument or sing their own songs by watching The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show back in 1964.

And at that same moment Kirsten was in Los Angeles, Southerners Duane and Gregg Allman were there chasing their own path with Hour Glass, recording with Liberty Records. Paul Hornsby, keyboard player, would later say their group already sounded like the Allman Brothers before there was an ABB. With Johnny Sandlin on drums and Pete Carr on bass, Hour Glass was living in the attic of a ramshackle house the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band called home in Beachwood Canyon, just below the Hollywood sign. Known as the “Dirt House,” it was equal parts bohemian crash pad and boot camp for musicians.

Hour Glass wasn’t mingling on Joni’s porch or trading riffs with Crosby and Nash, but they were playing the same clubs, steeped in the same atmosphere of invention — a crosscurrent of genres, restless players bending tradition into something new. Without knowing it, Kirsten would ultimately move through hotbeds that would define two coasts’ worth of American music. And one day those parallel sounds would finally converge in Macon, where two decades later she would get to know Gregg Allman and Paul Hornsby, all of them making an imprint on their adopted city.

For Kirsten, the contrast between the canyon’s open-door creativity and the Valley’s walled-off orchestration was part of the cultural revolution pressing in around her—a push and pull between freedom and control that mirrored the larger fractures of the era.

Hollywood was more than sunshine and soundtracks. The city bore the weight of its politics. Anti-war protests erupted on Sunset Boulevard, where Kirsten lived. In June 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel, and in August 1969, the Manson murders shattered the city’s aura of freedom, replacing it with paranoia.

Being in Hollywood was a crash course in contrasts; glamour and menace, beauty and fracture, idealism and violence. Kirsten was helping to design the rooms where Los Angeles entertained itself, while outside those walls the culture was both remaking itself and coming apart at the seams.

Years later in Macon, Kirsten would find echoes of those same LA tensions playing out in a different key. Here, the battle lines weren’t drawn between folk porches and studio walls but between church pews and rock clubs, between soul and Southern rock. Phil Walden had once managed Otis Redding, but after the deep loss of Otis’s tragic death in 1967, Walden pivoted Capricorn Records away from Soul and toward white Southern rock bands. The freedom of Black soul gave way to the control of a genre reshaped for wider (and whiter) audiences.

Race was always part of that push and pull in Macon. When the ABB got to town, they broke barriers as one of the first integrated bands in the South, and Grant’s Lounge — where they played often — became the first integrated music venue in Macon. Those choices were unusual, quiet defiance in a city where churches still thundered against the devil’s music.

Even so, young players packed into Grant’s on most nights, searching for transcendence in the jams. Capricorn’s studio turned those raw, communal nights into polished albums for national release, mirroring the same tension Kirsten saw in Hollywood — between grassroots expression and market-driven production. Macon wasn’t Los Angeles by any means, but it knew something about cultural collisions.

Settling in Macon many years later, Kirsten would join a city still wrestling with itself — a place where integration was fragile, hard-won, and always in need of tending.

But first she had to exit Hollywood.

Hartford, Chicago, and a Classified Ad

Leaving behind canyon nights and California’s kaleidoscope, Kirsten’s next chapter couldn’t have been more different — like stepping from Technicolor into grayscale.

After Hollywood, she spent time in Toronto, Canada, at the invitation of a friend — a whim she said yes to without hesitation. Staying with her friend’s family and living on savings, Kirsten took a job at a used-car dealership, cleaning out cars and changing oil. We can now add “mechanic” to her growing list of incarnations.

Eventually Kirsten followed a boyfriend to his home in Hartford, Connecticut — far from canyon nights, both geographically and philosophically. Hartford wasn’t fringed leather or glamour; it was buttoned-up, corporate, pragmatic. If Hollywood was all shimmer and risk, Hartford was beige carpet and actuarial tables calculating risk. And it was here that Kirsten began a 25-year career as an insurance executive.

It wasn’t the flashiest chapter of her story, but it gave her the stability and confidence to make her boldest leaps later — the kind that brought her to Macon and back into music’s orbit.

To some, that might look like a detour. To Kirsten, it felt like a new incarnation, proof she could thrive anywhere. The life was plush, even enviable, but to her it eventually felt hollow.

“Plush but vacuous,” she later admitted. She had the GQ husband back then, the executive title, the trappings of success, but she had little of what had first stirred her soul in Hollywood.

She might have traded bell-bottoms for heels and concerts for client meetings, but she still carried the same sharp attention she’d honed in California... and her love for music. Those corporate years gave her professional polish and executive acumen that she would later pour into Macon’s music institutions.

By the time Kirsten moved to Chicago, her marriage was behind her and she was ready to step into another incarnation, though she couldn’t quiet put her finger on what it might be. When she was shown a classified ad too promising to ignore, she took a small risk that opened up her next great chapter.

Meeting Kirk West

Kirsten had crossed borders, traded cities, and tried on different versions of herself, growing through every incarnation, and all those roads — from Hollywood to Canada, Hartford, Chicago — were quietly leading her to the one person that would change everything.

She met Kirk in February 1991 through a personals ad in the Chicago Reader — the first she had ever answered. The ad hadn’t been written by Kirk but by an ex-girlfriend. Over lunch, Kirk had confessed to her that while his life was good at 40, he was a bit lonely.

The ad written by Kirk’s ex-girlfriend read:

“MUSIC LOVING PROFESSIONAL Photographer, SWM, 40-year-old adolescent at heart, seeks warm feminine SF 28–45, with as attractive an interior as her exterior. If you’d enjoy hearing live blues with a long, blond-haired (okay, slightly graying) short guy (my friends’ description), call me. Do you have a great sense of humor?”

Kirsten’s co-workers were regular readers of the personals section, circling ads for sport. When they spotted Kirk’s, they insisted she had to call. Kirsten felt a tug in her gut that this was something she shouldn’t ignore. She dialed the number in the ad, listened to Kirk’s recorded message, and left one of her own.

It was a leap, but Kirsten had always been open to leaps, and to the idea that life might be nudging her toward something significant. Looking back, it’s not an exaggeration to say that call changed the cultural map of Macon. Left to their own devices, Kirk and Kirsten might never have met — which means there might never have been a Big House Museum or Gallery West. All of it traces back to an ex-girlfriend with a pen, a few office friends encouraging her, and Kirsten, as usual, trusting her instincts enough to say yes.

Kirsten and Kirk spoke for 90 minutes before they met, and after their first date Kirk was telling friends he had known she was the one within the first thirty minutes they were together.

By September, they were married.

Kirk was already deep in the whirlwind as Road Manager (aka Tour Mystic) for the ABB, hard work, yes, but not tied to an office chair. Kirsten, by contrast, had spent years in the buttoned-up world of insurance. Marriage to Kirk opened a different kind of door for her, one that aligned with the restlessness she’d been feeling. She was more than ready to trade policy numbers and endless meetings for something with soul.

Not long after, Kirk showed her some photographs from a recent trip to Macon — images of a house he just toured, the former communal home where the Allman Brothers once lived and jammed.

Those pictures lit a spark.

It wasn’t gold records or guitars that caught Kirsten’s imagination. She respected the band’s mythology, but that wasn’t what moved her. What she felt was the possibility inside those walls — the sense that the house itself was calling for a steward. Almost without thinking, she told Kirk they should turn it into an Allman Brothers Band Bed & Breakfast.

That instinct would become her compass for the next three decades.

Kirsten came to Macon with an open mind and within a year she was buying the Big House, managing its renovation, and preparing to open its doors to fans from around the world. She hadn’t been part of the original ABB inner circle. She didn’t play guitar or have a Southern accent. Yet, she’s the one who wanted to keep the doors open, the archives safe, the memories alive.

Every turn had been pointing Kirsten first to Kirk and then to Macon. It seemed inevitable that they’d relocate there in 1993.

That ad she had answered was the hinge that swung her whole life toward the work of preserving a legacy and, in time, becoming part of that legacy herself.

Restoring the Big House

Macon wasn’t Hollywood but it had its own gravity. The town was smaller, slower, rooted in red clay and magnolia shade — but the music rising out of it was just as world-shaking. Capricorn Records had turned this sleepy Southern city into a launchpad for the ABB and the Southern Rock wave that followed. For Kirsten, who had already seen in California how culture could explode, Macon carried that same electricity: tradition colliding with change, community wrestling with identity, and music somehow making sense of it all.

The Big House wasn’t a historic site or shrine. It was just an old house on Vineville Avenue — weathered, crumbling, half-forgotten, and bursting with stories. Kirk and Kirsten were determined to take the Big House out of the past and into people’s lives.

“It was my idea to buy the house, and my money that bought it,” she tells me plainly. “I managed the renovation while Kirk was on the road with the band.”

The Big House as it stands now, a living museum of Southern Rock. Without Kirsten West’s steady hand and imagination, its doors might never have opened to welcome fans from around the world.

When they moved into 2321 Vineville Avenue, they were stepping into a myth and a money pit. The Tudor home that once sheltered Duane Allman, Berry Oakley, and the larger, tight-knit ABB family had fallen into disrepair — water damage, crumbling stucco (even false stucco in places), failing ceilings, leaking roof, broken showers, and knob-and-tube wiring so old the entire house needed rewiring before the heat could even be turned on.

Thankfully, friends showed up to help. Kyler Mosely — now the driving force behind GABBA and Skydog festivals, and The Whipping Post show on 100.9 The Creek — was there hauling boxes, helping Kirsten and Kirk move not just into the Big House, but into a whole new way of living.

Kirk went on the road with the band and Kirsten stayed behind, working with Tory Torstensen, a former Grinderswitch road manager-turned-general contractor, who managed local tradespeople as they upgraded the house. Larry Brantley, once Dickey Betts and Lamar Williams’ guitar tech, showed up as a cabinet maker, building miracles. Not every tradesperson was from the Southern Rock world, but it’s fun to notice the ones who were.

Fans drove from as far as California and Maine to hang sheetrock and paint; some even slept in the half-gutted rooms while they worked. Kirsten kept the entire operation moving — ordering windows, wrangling inspections with Macon’s zoning board, keeping volunteers fed, and finding money where there was none.

“It wasn’t until after Thanksgiving,” Kirsten wrote in ABB fan magazine Hittin the Note, “that Kirk and I were alone in our new home for the first time. We have welcomed the peace and quiet — although with two dogs and a cat, it’s not that peaceful.”

Peace was rare. The house was filled with music, hammering, and the constant buzz of visitors.

And yet, she made it work. Slowly, the Big House transformed from a decaying wreck into a shining showcase. Kirk’s collection of ABB relics — tapes, posters, instruments, stage clothes, Duane’s custom-designed mushroom pendant — found a permanent home. The Archive Rooms took shape in the former parlor and practice room, lined wall-to-wall with framed memorabilia. Volunteers installed windows, mounted posters, and hung track lighting just in time for reunion weekends and GABBA events (That’s the Georgia Allman Brothers Band Association). By the time the first visitors walked through, Kirsten had managed the miracle of turning chaos into preservation.

It was more than drywall and wiring, though. It was spirit. Kirsten played hostess as much as project manager — opening her doors to ABB family, musicians, and fans from around the world. Mama Louise Hudson from H&H Restaurant came, as did Berry Oakley’s widow Linda, Gregg and Mama A, Col. Bruce Hampton, Derek Trucks, Warren Haynes, and legions of wide-eyed devotees. Two young women from Croatia showed up on their doorstep after a transatlantic journey, exhausted and nearly in tears. Kirsten and Kirk welcomed them in, gave them beds, and turned their pilgrimage adventure into part of the Big House story.

On the front steps of the Big House:

Kirk West, Kirsten West, and Gregg Allman. In 1968, both Gregg and Kirsten were in Hollywood, moving through the same orbit before their paths crossed again years later in Macon. The house where the Allmans once lived — and where Berry Oakley died — might have been lost to time, but Kirsten’s determination helped preserve it as the museum fans know today.

Originally published in Macon Magazine.

In 1996, Kirsten and Kirk partnered with Bill Lucado to purchase 2305 Vineville Avenue, a smaller Tudor next door, and named it the “House of Music,” using the space as both a rental and a workhorse (and receiving an award from the Macon Heritage Foundation for their renovations). The House of Music served partly as the fulfillment center for Kid Glove Enterprises, where ABB merchandise was boxed and shipped. Artist Johnny “Mo” Mollica lived there as their first renter and ran his t-shirt design shop, enjoying a friendship started on the ABB road with Kirk and enduring with the Wests to this day.

The renovation work on the Big House was grueling and budget-battering, and it seemed endless, but those improvements mattered. Alongside the sawing and stream of visitors, there were whispers and signs that reminded Kirsten and Kirk they had stepped into something larger than themselves.

From posters on the walls to instruments under glass, the Big House tells the Allman Brothers’ story in vivid detail. What began with Kirk West’s collection grew into a full museum — and the fact that fans can walk these rooms today owes much to Kirsten West’s vision and determination.

Haunted, But Home: Signs and Spirits

Even before they signed the papers, Kirk and Kirsten wondered if they were out of their minds. The Big House was run down, Macon was far from their established lives in Chicago, and the whole idea felt like a gamble with no safety net. She was still an insurance executive, after all, and giving up the benefits and safety of a corporate job wasn’t easy. So they looked for signs, hoping for reassurance.

As they were leaving their Macon hotel to visit the house for Kirsten’s first time, they both knew they wanted the house more than anything, and that much wanting made them very nervous. Kirsten wrote:

“So we jumped in our rental car, turned on the radio and stared at each other in disbelief as we heard the very beautiful familiar strains of ‘Dreams’ swirling around us. Both of our hearts were pounding. The Big House was a dream for us and one that we were praying would come true.”

When Kirsten stepped into the house just moments later, she knew she was home. They both fell in love with its bones and its history, but fear lingered as the degree of disrepair sank in. Could they really uproot their lives for this massive renovation project? They needed time to think and discuss their options.

Kirsten wrote:

“So we got back in the car to go to the hotel and regroup, turned on the radio only to hear ‘Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More.’ Well, that put aside any doubts I might have had. This was to be and we just had to figure out how to make it happen.”

This was to be. The music itself was telling them to leap.

That leap was more than just real estate. It was an act of faith — in music as a messenger, in the unseen as a guide, and in their own courage to create the future they wanted. Taking that leap, any leap, aligned with who Kirsten was at her core. She had lived as a hippie in California, walked away from a comfortable but empty marriage, and built a new, unpredictable life with Kirk that carried her places she never imagined. Kirsten had said yes to every opportunity, even the wild ones — like scuba diving in Fiji during a military coup.

Kirsten’s father, Chuck Olson, seemed to have passed that openness to Kirsten. At 87, he was ill and not expected to live more than six months, but he went to Macon with Kirsten and found his resilience, recovering and eventually able to travel back home, his good health a result of Kirsten’s careful caretaking.

So when the female ghost began to appear at the Big House, Kirsten met her the way she met every adventure: open-eyed, unflinching, and ready to make meaning from the encounters.

She has written and spoken candidly about the apparition both she and her father saw during the during renovations, and later, describing a figure in a long dress with ruffles down the bodice and a bonnet.

“We were first told about her by the former owner, and also by Linda Oakley Miller, Berry’s widow,” Kirsten says.

Her father reported seeing the young ghost twice. Once he asked Kirsten if she had come into his room brushing her teeth, only to realize it couldn’t have been Kirsten because the figure was wearing a bonnet. Another morning, he told Kirsten his late wife had hovered over his bed, drifting from side to side, before conceding that the bonnet meant it was someone else entirely. Linda Oakley, too, once described to Kirsten how the same presence had hovered over her while she was in bed.

Other signs were subtler but no less uncanny. Keys vanishing, then reappearing in impossible places. Mascara disappearing from a windowsill and returning weeks later to the very same spot. Glasses relocating from Kirsten’s bedside table to Kirk’s. More than once, rooms filled suddenly with the scent of cinnamon — sometimes while she was alone, once with friends piled into bed watching The Sopranos, all of them startled by the invisible hand at work.

Kirk later told Carrie Genzel, hostess of the online ghost-hunting show Macon Beyond, that they had been warned from the start: the ghost had a habit of pushing women on the stairs. Kirsten herself was pushed several times and once spent weeks recovering. Unlike others who might have fled, Kirsten stayed.

Perhaps it was her own mystical bent that steadied her. Kirsten had always been tuned to energy — meditating, exploring channeling, and practicing her own quiet form of hands-on healing. She credited her touch with extending her father’s life and even saving her cat’s injured eye. Animals seemed to sense it too. On dives around the world, dolphins would swim straight to Kirsten. During her first ocean dive, in Jamaica, a pod circled her as she stood on the ocean floor and other divers watched from outside the circle, taking photos she wishes she still had.

Another time, a lone dolphin off Palau played with her, following the line from the anchor up to meet Kirsten nose-to-nose, and then going down again. Later that day, warnings of a hurricane forced them back to shore, where they helped the boat’s captain batten down the hatches, and then Kirsten and her husband flew out, later learning the hurricane had sank the captain’s beautiful, hand-made boat. Had the dolphin been warning them of the coming storm, urging them to lift anchor and skedaddle? Kirsten thinks so.

People respond to her energy as well. Friends she met decades ago, such as Mike Farris, lead singer of the Screaming Cheetah Wheelies, still text her nearly every day.

“I think energy lingers,” she told me, thinking of the ghost but also the energy of the living… living on in spaces. And drawing others closer.

She had felt the unseen guidance in music that arrived like a sign, in the dolphins who always found her, and in the Big House itself.

Macon Beyond host Genzel also shared that the show’s spiritual medium Morrighan Lynne had stood quietly in the museum room and felt not menace in a bonnet, but kindness: five spirits of ABB members came to her, the nicest spirits she had ever encountered, she said, wanting only to know if what they had done was important. Her answer was simply “Yes.” They were standing in their own museum, where thousands of fans from around the world come each year to honor them. That part didn’t make it into the episode, though.

In the Big House, Gregory Pentley’s portrait captures the Allman Brothers Band in vivid color — framed by the gold records that testify to the music born within these walls and perhaps still echoing with the spirits of the men who made it.

In that sense, the Big House has never been just walls and staircases. It is a vessel where past and present meet, where ghosts brush up against the living, where energy lingers, and Kirsten’s courage to embrace the unseen was fueled by her adventurous spirit.

None of it felt out of step to Kirsten. From hearing songs as signs… to living with spirits in the hallway… she moved through the world with an openness to meaning and mystery, carrying her and Kirk through decades of preservation in Macon.

Even the ghost became part of the story she was preserving, another layer of Macon’s rich history folded into the house. And while the Big House held all that energy, Kirsten’s words published in Hittin’ the Note opened its doors even wider, carrying the stories of Macon and the Brothers to fans around the world.

Kirsten at the Crossing: The Station Master

Kirsten West stood at the Crossing, minding its commotions. The Big House wasn’t at a literal crossroads, but that’s what it became under her care—a place where stories and people met.

“Almost from the day we arrived,” Kirsten once wrote, “we have had some groovy guests.” What an understatement!

Musicians rolled in from every direction, sometimes announced, sometimes not, and the Wests always opened the door. Like the clang of a railroad crossing, each visitor carried the thrill of possibility: who’s coming down the tracks this time?

Some came to crash on the couch, some came to rehearse, and others simply stopped in for coffee and stories before moving on. Beyond the threshold, the Wests were also out in the world showing up at gigs in Atlanta, catching a rising act in Athens, or cheering on a local group.

Through the 90s, the Big House became Macon’s unofficial Southern Rock station, and Kirsten was the Station Master—logging arrivals, opening doors, and making sure each guest became part of the story. Their guest book would read like a living ledger, and luckily Kirsten captured much of it in her regular “Big House Updates” column in Hittin’ the Note.

The roll call through the first few years is staggering. Reese Wynans dropped by, bringing along Lee Roy Parnell and James Pennebaker. Tinsley Ellis slept in Duane’s old room, serenading the house at night and again in the kitchen the next morning. Derek Trucks showed up at fourteen, already blazing on guitar. Jack Pearson played “Little Martha” in Duane’s room late at night, a moment Kirsten described as if unseen ears were still listening. Skeeter Brandon spent his visit planted at Gregg’s Hammond B-3, singing and playing as though the house itself was his audience.

And a revolving parade of players, producers, reporters, and friends kept arriving: Bill Levenson from Polygram, Ian Moore, Screaming Cheetah Wheelies, Freddy Jones Band, W.C. Clark, David Grissom, Rod Piazza and the Mighty Flyers. Tim and Gregg Brooks even signed their record contract in the living room, breaking the sofa in the process. There were the ABB family ties, too—Butch Trucks bringing an original Fillmore East snare, Berry Oakley Jr. with his mother Julia Negron and his band Bloodline, Jaimoe with his wife and daughter, Gregg Allman and his full band and crew, and Linda Oakley returning for the first time since Berry’s death.

Multiply this sampling by years and you begin to see the scale. Kirsten was exposed to an endless flow of musicians and styles, gathering knowledge all the while. By the time she interviewed Lucinda Williams in the early ’90s, she was already encyclopedic in her understanding of who was out there and what they sounded like.

Imagine what she knows now.

Publisher of Hittin’ the Note

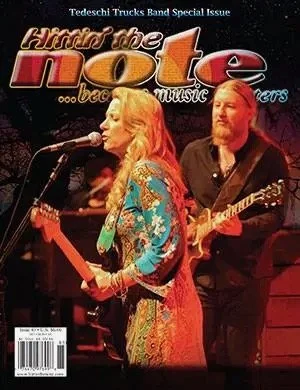

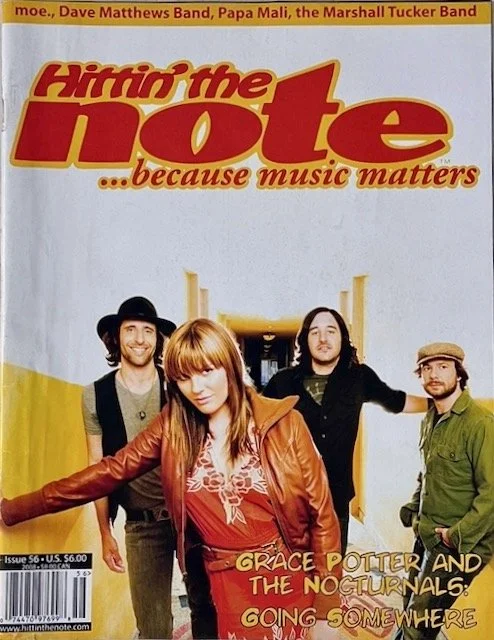

While hammers rang through Vineville, Kirsten kept her hands on another legacy project: Hittin’ the Note. Launched by Kirk West, Ron Currens, Bill Ector, and Joe Bell in the summer of 1992, the newsletter-turned-magazine grew from a 16-page black-and-white fan bulletin — photo-copied, stapled, and mailed — into a full-color glossy publication carried at Tower Records, Barnes & Noble, and Borders.

For five pivotal years, Kirsten served as publisher, steering the magazine through its early growth and helping it become the voice of the ABB fan community. She managed production schedules, distribution, and the business side of keeping it afloat, while also writing, interviewing, and reporting. Her “Big House Updates” became a lifeline for fans eager to stay connected to the band and the house that had once been its beating heart.

Even after she stepped away in 1998 and Joe Bell took over as publisher, the magazine carried forward the momentum she had helped build. That work — preserving ABB history, connecting fans across the country, and turning news into narrative — was part of the same calling that led her to manage Blueground Undergrass, guide singer/songwriter Diane Izzo, and later breathe new life into the Capitol Theatre.

The first issue of Hittin’ the Note (1992), launched as a fan-club newsletter for the Allman Brothers Band. Its name came from the band’s own phrase for the transcendent moments of complete oneness when the music, the players, and the audience all locked together.

More than a title and more than the music, “hittin’ the note” was considered a way of being by Berry Oakley and it became a mission on-stage and off, and in print — to capture and preserve those moments, keeping the spirit of the band alive for fans everywhere. Over the next 23 years, the newsletter grew into the most enduring chronicle of the Allman Brothers Band.

Through her updates, Kirsten documented not just the band’s activities but the day-to-day life inside her home. Hers is a singular perspective in all the world, with a story only she can tell.

Kirsten wrote candidly about plumbing failures and disappointing electricians. She wasn’t afraid to dig deeper elsewhere in the magazine as she reported from the ABB’s 1995 induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, noting who attended, what they wore, and what was said from the stage by each band member or their children.

Kirsten’s voice combined the awe of a fan with the precision of a journalist.

A sampling of Hittin’ the Note covers, 1992–2015.

From the early black-and-white newsletter to the glossy full-color issues that landed on newsstands nationwide and internationally, the magazine carried interviews, essays, history, fan voices, and photography that documented not just the ABB, but the wider world of Southern rock.

The Chronicler

Two of Kirsten’s updates, from issues #5 and #7, stand out as proof of how she became the parallel historian of Southern Rock—documenting the home front while Kirk documented the road.

In Issue #5, she went beyond reporting on renovations and turned her journalist’s eye toward the women who had first discovered the Big House. Sitting down with Linda Oakley, Ellen Hopkins, and Willie Perkins, Kirsten captured the story of how the house was found in a classified ad, how the band families moved in, and what those years between 1970 and 1973 really felt like.

“Three women and two children were the real permanent residents of this house,” Kirsten wrote of Linda with her daughter Brittany, Candy Oakley, and Donna Allman with her daughter Galadrielle. “Any notion that this was a big hippie crash pad are obviously mistaken.”

In that single observation, Kirsten reframed the mythology of the Big House, reminding ABB fans that, for all the legends and late-night jam sessions, it was also a home.

So powerful was Kirsten’s write-up about the house’s history, the update became the backbone of the “official” Big House origin story published on the museum’s website today. Her name doesn’t appear, but her voice is unmistakably present.

For anyone who wants to feel the same impact Kirsten felt when talking with Linda and Willie, watch Kirk’s documentary Please Call Home. Speaking softly but with authority, Linda tells stories of meaning and paints scenes so vivid you feel as if you’re standing in the house with her back in the 70s.

Kirsten’s update in Issue #7 stretched across six pages, and reads like a time capsule, revealing her incarnation in a new light. She was hosting musicians and friends, and also welcoming tradesmen and volunteers into the orbit of the Big House. As Kirk spent long stretches on the road with the band, Kirsten was often alone in Macon, keeping things moving.

“The house was so warm and inviting—even without furniture. It just felt good,” she wrote. “I must admit that on that first evening and for the rest of the week as well, when I left this empty house I felt like I was abandoning a child. The house seemed alive to me.”

That sense of caretaking, of treating the Big House as something vulnerable and alive, defined her Station Master incarnation.

Her quarterly updates mixed that kind of emotion with humor and hard facts. She chronicled the endless repairs, the wiring, the windows, and the roofing.

“Does it sound like we rebuilt the house? We did,” she concluded, just five months after moving in.

That same update broadened the story to Kirk’s archives, with Kirsten tracing his collection back to his very first ABB relic: an Allman Brothers/Hot Tuna poster from the Fillmore West in January 1971.

“He was actually there for all four shows and still has the poster,” Kirsten wrote after interviewing Kirk, linking his personal history with the museum-in-the-making.

And amid the chaos of contractors and cardboard boxes, life kept arriving at her doorstep. ABB roadie Joe Dan Petty and his wife Judi gifted the Wests an eight-week-old Jack Russell puppy, Lizzy, who became part of the family lore.

In all of this—contractors, volunteers, visitors, archivist husband, trips to support musicians, dog and cats—the pattern is unmistakable. Kirsten was running the station. She kept the log, welcomed the arrivals, managed the departures, and ensured that the Crossing was always harnessing the bustling energy wisely.

Kirsten’s role as Publisher gave her stewardship. The way she tended the magazine was the same way she tended the Big House. She was telling their stories and carrying it straight to the fans who cared the most. That’s why she’s the Godmother of Southern Rock, a title she has quietly embodied for decades.

The Content of Hittin’ the Note

The first issues of Hittin’ the Note reveal just how ambitious the magazine was, even when it was still a fan-club newsletter. Each issue was a mix of history, fresh reporting, archival digging, and personal testimony that no other publication could have captured.

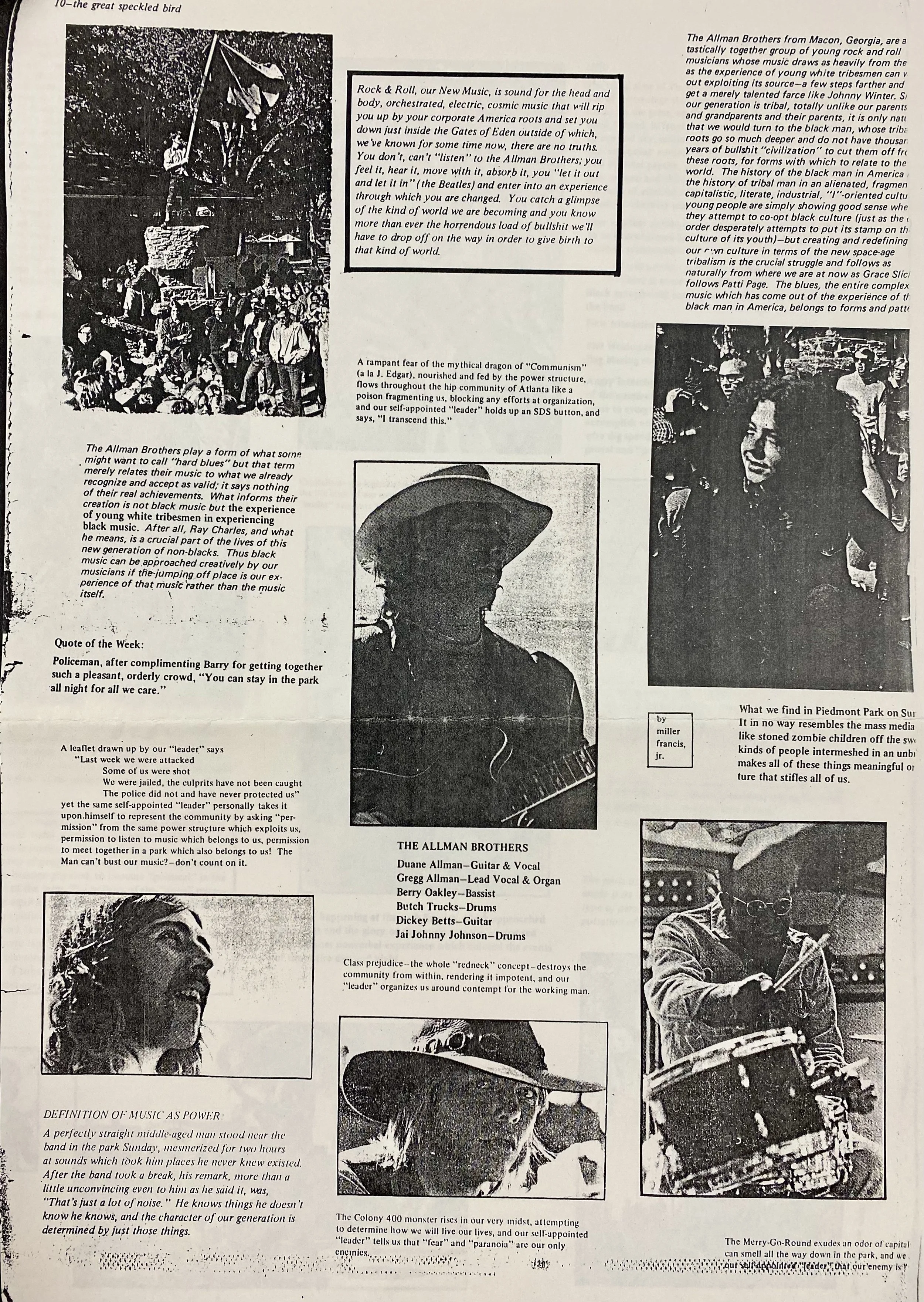

The very first issue opened with John Ogden’s First There is a Mountain, an extended, three-part narrative tracing the Allman Brothers Band’s origins. Part One dropped readers straight into Piedmont Park, May 11, 1969, where Duane, Gregg, Dickey, Berry, Butch, and Jaimoe plugged in for their first free concert as a band.

Ogden described the scene in cinematic detail. By choosing this as its very first feature, Hittin’ the Note announced its purpose: to enshrine not just facts about the Allman Brothers, but the lived, electric experience of their music.

From the pages of The Great Speckled Bird (April 1969):

These rare images capture the Allman Brothers’ first free concert at Piedmont Park. John Ogden’s opening essay in Hittin’ the Note looked back on this very day, describing the Brothers’ arrival as both a shock and a revelation; a new sound rising from the South that swept through the park with the force of history, community, and rebellion.

From that first serialized article, Hittin’ the Note’s content only deepened. Tom Dowd, the legendary producer, contributed a sprawling 9½-page memoir in his own words, reflecting on decades in the studio with the ABB. Recurring columns kept the ABB community connected — From Macon, GA, Where It All Began… provided regular GABBA updates, chronicling the preservation work of the fan-based group.

Profiles of band members ran in depth, from two-part interviews with Warren Haynes and Allen Woody to a reflective piece by Kirsten herself, Inside the Elusive Mr. Betts, where she captured the more private side of Dickey Betts that most fans never glimpsed. Other issues paired interviews with reflections from fellow musicians, weaving in voices like Marc Quiñones, as well as outside contemporaries such as Lee Roy Parnell, Steve Earle, and many others.

Contributing writers broadened the scope well beyond ABB. Articles explored the blues and jazz foundations of the band’s sound, the careers of Georgia promoters and fellow musicians, and first-hand accounts of rock history. Writers like Roger “Hurricane” Wilson, David Lynch, Bill Ector, Kim Ploch, Bill Bader, John Lynskey, Dean Budnick, Lana Michelizzi, and others gave the magazine a chorus of perspectives.

And we can’t forget Kirk’s famous dispatches from the road in Hittin the Note: Hot Poop & Innuendo. While Kirsten’s voice was the steady beat, Kirk’s column opened with irreverent greetings like “Howdy, Shitheads!” and then careened through road gossip, set lists, personal asides, and fan shout-outs.

Over time, Hittin’ the Note became the connective tissue for the Allman Brothers’ community and the definitive chronicle of Southern rock, written from the inside out. It carried on the tradition of Kirk’s Les Brers ABB fan newsletter published in the 80s, which today is also a deep archive of ABB history in print form.

Kirsten’s hand was everywhere in Hittin’ the Note — in the editorial calendar, in the merchandise, in the words on the page. For twenty-three years, the magazine carried the ABB and Southern Rock story forward, even as the band itself spun through breakups and reunions.

Kirsten’s incarnation as Publisher became a well-deserved identity. She poured herself into the work the way others might pour themselves into performance or painting. Every issue meant late nights of editing, proofreading, wrangling with printers, and lugging stacks of magazines to the post office. It was often unglamorous, meticulous work, but it carried weight.

Her steady work ethic and Kirk’s ability to harness volunteers, contributors, and fans turned what could have been a flimsy newsletter into a publication of record. Hittin’ the Note documented the Brothers not as distant rock gods but as a living, breathing band whose story was still being written, and it gave Macon a voice that reminded the wider world: the music minted here still mattered. It’s later motto literally declared “…because music matters.”

Hittin’ the Note’s legacy is twofold. First, it preserved the past in a way that became invaluable to scholars, journalists, and future fans — today, its back issues are cited alongside books, documentaries, and museum displays. Second, it modeled a new wave of music journalism: grassroots, community-driven, fiercely independent, but executed with professionalism and heart.

Kirsten helped build a body of work that captured not only the ABB’s story, but her own as well. When the publication ended in December 2015, Kirsten and Kirk were putting their energy into Gallery West, where their photographic and curatorial work would continue the preservation in a new form.

Dinner at the renovated Big House, home of Wests, meant more than food. Here, Kirsten serves her home cooking to Judi Petty, Chris King, Bonnie Bramlett of Delaney & Bonnie (her hero), and Dru Lombar of Grinderswitch: a snapshot of the life she built, where her dining table became as vital to Southern Rock’s story as any stage. Originally published in Macon Magazine.

Managing Blueground Undergrass

As if restoring a crumbling Tudor mansion, hosting guests and volunteers, and running a music magazine weren’t enough, Kirsten also found herself pulled into band management. One day the phone rang — Col. Bruce Hampton was on the line. His request was simple and impossible to refuse: would she take on the management of a new group he believed in, a jam-bluegrass fusion outfit with Rev. Jeff Mosier called Blueground Undergrass?

Kirsten said yes. She began booking shows, handling logistics, and guiding Blueground Undergrass through its early steps, drawing on the same organizational muscle she used daily at the Big House and Hittin’ the Note. She understood the rhythms of musicians’ lives and the practicalities of keeping a band on the road.

By then, she had already been shaping the local music scene in Macon — booking acts into Alan Frank’s rock club Rivalry’s on Cherry Street (later Elizabeth Reed’s Music Hall) for its beloved “Blue Monday” shows. Kirsten’s idea was simple but smart: start the shows early to draw a Monday-night crowd, and book touring acts passing through Georgia on their way to bigger gigs in other states. Those bands might never have played Macon otherwise, but on a Monday night they could drop in and play an intimate set.

Her bookings turned Monday nights into a gathering place for musicians and fans — a space where the scene could stretch and hear national acts they might not have caught anywhere else. It was an early glimpse of what she would do later at the Capitol Theatre, where she brought in acts and made sure they were treated like honored guests.

Kirsten also managed Diane Izzo — a gifted but troubled eighteen-year-old who would become like a daughter to her. Kirsten took Diane under her wing, even moving her into her home, and when Diane decided to get serious about her songwriting, Kirsten became her manager. She learned the business on the fly, booking Diane into respected LA clubs, recording demos, and pitching her songs to publishers and record companies.

The partnership didn’t last forever — Diane struggled, and eventually they went their separate ways. But they found their way back to each other years later, and Kirsten said yes once more. She helped Diane relaunch her music and supported her through a second, more focused attempt at a career. It didn’t lead to fame, but it mattered.

When Diane was diagnosed with a brain tumor many years later, Kirsten was there again, visiting her until the end. After Diane passed, her family turned to Kirsten to help them reclaim Diane’s story. Kirsten gave them two boxes — one filled with papers and letters she’d written to publishers and record companies, and one filled with the recordings Diane had made. Kirsten had forgotten how much she had accomplished for Diane until she saw it all laid out together.

“It reminded me what I could do when I put my mind to something,” Kirsten says. But it also reminded her of something else: that she didn’t want to spend her life in the music industry. “It’s hard. I just wanted to enjoy music.”

Kirsten and Diane’s connection was never simple, but it was enduring. Kirsten kept showing up through the whole arc of Diane’s life — from a hopeful teenager, to a struggling artist, to a woman facing the end. That steadfastness shows another facet of Kirsten’s character: her willingness to invest in people, even when it’s messy, and to stay until the last page of their story is written.

Kirsten’s management of Diane and Blueground Undergrass placed her in the lineage of independent managers and promoters who kept Southern rock and its offshoots alive outside the machinery of major labels. It also showed her gift for sensing when music needed a champion — and stepping in with exactly the right mix of structure, care, and stubborn faith to help it flourish.

For fourteen years, Kirsten and Kirk made the Big House their home. Then, a friend’s suggestion to turn it into a museum sparked the creation of the Allman Brothers Band Foundation. With Kirk’s ties to longtime ABB fans on Wall Street, donations in the millions poured in, and they sold the house to the foundation. What began as a quirky B&B dream became something larger still: a museum, a publishing firm, a crossroad, and the beating heart of Southern Rock, now open for anyone searching out its roots and living spirit. That energy still lingers.

Through the Big House and Hittin’ the Note, Kirsten and Kirk built something that outlasted both the glory and the wreckage of ABB’s stardom. But Kirsten wasn’t finished. The same instinct that led her to book Monday-night shows, manage a young songwriter, and give a jam band its first shot would soon lead her to breathe life into another Macon landmark. When the call came from the Capitol Theatre, Kirsten stepped into yet another incarnation.

Capitol Theatre: Let’s Do Something

The Capitol Theatre had stories baked into its bricks before Kirsten ever walked through its doors. Opened in 1916 with leather seats and a gold-fiber screen, this downtown landmark was once the city’s entertainment hub — screening silent films beneath ornate plaster ceilings, hosting vaudeville acts, and later becoming a hotspot for movies, concerts, and community gatherings.

Like many grand theaters, the Capitol had slipped into disrepair and sat empty for years, until Tony Long of A.T. Long & Son Painting Contractors began a painstaking and beautiful renovation in 2003, culminating with the theatre’s reopening in 2006. Tony simply could not stand the thought of the building decaying into disuse, so he did something.

By the time Kirsten showed up, the place was gorgeous and long on history, but short on vision.

“I wasn’t hired to save the theater,” she told Macon Magazine, “but that’s basically what ended up happening.”

At first, her job was raising funds, so she threw a big fundraiser and packed the house. But she quickly realized no one wanted to donate to a venue that wasn’t putting music on its stage.

“I said, look, I can’t raise money for an organization that isn’t doing anything. So let’s do something,” she recalls.

What followed was classic Kirsten: less hand-wringing, more doing. She cleaned out the office (even scrubbed toilets), brought order to the chaos, and picked up the phone to start booking acts.

Travis Tritt. Chuck Leavell. Lucinda Williams. Marty Stuart.

“I wasn’t just booking bands,” she says. “I was rebuilding the damn venue.”

As Kirk often points out about Kirsten’s executive abilities: she gets things done. Fueled by instinct and that stubborn love for live music, she gave the Capitol a new spin.

Her secret weapon? Years on the road witnessing Kirk and the ABB. She knew what touring musicians actually needed: good sound, a hot meal, and someone who respected the grind.

“We booked ’em, fed ’em, and treated them right,” she says.

It wasn’t just hospitality. It was stewardship. Again.

With Kirsten at the helm, the Capitol got its groove back. It became more than a building — it became a place to be. A stage worth standing on. A venue with roots and resonance. And like everything else she touches, Kirsten didn’t just fix it; she made it feel right.

Even now, as Macon’s music scene surges again, you can trace the roots back to her handiwork. Last August 2025, the band Trouble No More — carrying forward the Allman Brothers’ torch — returned to the Capitol stage for two nights of music that bridged past and future.

That’s legacy. That’s impact. That’s Kirsten.

She helped Macon reclaim another of its crown jewels, and she did it the way she always does: by rolling up her sleeves and asking, “Okay, guys, what needs doing?”

April 2010: Gregg Allman, Jaimoe, and Butch Trucks cut the ribbon to open the Big House Museum. The ceremony marked a new chapter for the home where the band once lived — made possible by years of groundwork from Kirsten West and the vast collection Kirk West had preserved, together ensuring the house would welcome fans for generations to come.

Ribbon-cutting photo from The Big House Museum archives.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Let the Music Die

By the late 2000s, Kirsten’s energy had outgrown the Capitol’s walls. She had revived two historic venues — now she wanted to revive the idea of Macon itself. Her mission widened, from saving a single theater to safeguarding the story of Georgia’s music.

In 2008, when word spread that the Georgia Music Hall of Fame was on the chopping block, Kirsten West refused to let the lights go out on the state’s musical story. The museum’s director, Lisa Love, had confided that legislative funding was evaporating and no private donor could fill the gap. To most people, that sounded like inevitability. To Kirsten, it sounded like a challenge.

Kirsten and Lisa have remained dear friends ever since — two women who’ve spent their lives defending Georgia’s music and the people who make it. These days, Lisa lives in South Carolina, closer to her husband’s aging parents (he’s a member of the Marshall Tucker Band), but she still returns to Macon often when he’s out on the road — keeping one foot planted firmly in the city she helped shape.

When Lisa broke the news of the Hall’s precarious future, Kirsten called on her friend Rabbi Larry Schlesinger, a fellow believer in the gospel of civic duty, and the two drove to Atlanta to speak at the Hall of Fame Board’s committee meeting. With her usual mix of conviction and charm, Kirsten reminded them that the museum wasn’t just about preserving memorabilia — it was about protecting Georgia’s voice.

Afterward, she sought out anyone with influence or empathy: Beverly Blake of the Knight Foundation, Bibb County Commissioner Sam Hart, and Macon Mayor Robert Reichert. One by one, they listened, and one by one, they found ways to help. The Knight Foundation gave $20,000. The county matched it. The city did too. By the time Kirsten was done, she had raised $60,000 — enough to keep the museum alive for one more year.

It wasn’t just the money that mattered — it was the coalition she built, the sense of possibility she rekindled among people who’d nearly given up. It wasn’t a permanent victory, but it was a bright one. The Hall eventually closed, its artifacts boxed up and sent to the University of Georgia’s archive in Athens, or to other Georgia cities for storage. For that one reprieve, Kirsten had proven what she always believed: you can keep something breathing if you love it hard enough.

That same year, another storm was brewing — the economy teetering, the Big House still becoming a museum, the city in flux. Where others saw collapse, Kirsten saw an opening.

She had been reading about John Elkington, the man who’d turned Memphis’s Beale Street into a thriving home of the blues. Why not Macon, she thought, as the Home of Southern Rock? She tracked down Elkington’s number, left a message explaining her idea, and waited. No reply. So she went to her ally Beverly Blake at the Knight Foundation, who said simply, “Let’s go to Memphis.”

They planned the Memphis trip and let Elkington know they were coming, but did his homework on Macon’s music history and became curious enough to make the trip to Macon himself.

Kirsten reserved the Capitol Theatre for a community meeting. She invited everyone she could think of — NewTown Macon, business owners, nonprofits, musicians — and hoped a handful would show up on a Tuesday afternoon. Instead, 300 people packed the room. Elkington spoke first, but when Kirsten took the stage, she electrified the crowd.

“I’m a fabulous extemporaneous speaker,” she says now with a wink, and back then she was pure fire — describing a city reborn through its own soundtrack. She imagined Poplar Street lined with new businesses carrying Southern Rock names: Sweet Melissa Bakery, Midnight Rider Café. She pictured the Big House Museum as the anchor, the Capitol and Douglass Theaters thrumming, Grant’s Lounge alive with live music again — a city singing its way back to life.

She was so good at the podium, John Elkington tried to hire her as soon as she stepped off the stage. Others loved her ideas, too, and a committee was formed. Unfortunately, committees are known to be the quickest way to kill an idea, any idea. Especially good ideas. Politics, too, got in the way, as it tends to.

When the economy crashed, funding dried up and momentum stalled. Kirsten declined to join the newly minted Macon Music District Committee — partly out of exhaustion, partly out of principle. “Some men don’t know what to do with strong women and good ideas,” she says, half with humor, half with truth.

Without Kirsten’s energy, the committee did very little until the whole thing fizzled out.

Yet her idea didn’t die. It simply took root, lying dormant, waiting for the world to catch up. Years later, Macon’s motto would become “Where Soul Lives.”

Today, Visit Macon, the city’s tourism and cultural hub, carries that torch, marketing Macon’s musical heritage to the world: Otis Redding’s Foundation, Little Richard’s childhood home, Capricorn Records, The Creek 100.9, and The Big House Museum itself. The very constellation Kirsten once envisioned.

“I guess it’s better it didn’t happen back then,” she says now, grinning. “Would we really want Macon to be like Beale Street?”

Maybe not. But there’s no question the seed she planted bloomed in its own time. Her vision was practical and brave — a belief that art and civic life could work in harmony if someone was willing to fight for both. Kirsten knew Macon’s creative history could be both its compass and its calling card.

In saving a museum, she safeguarded a history. In imagining Macon’s future, she helped give it a map. And that may be the truest measure of her legacy — not just what she preserved, but what she made possible.

Her fight for the Georgia Hall of Fame and her vision for Macon’s future weren’t isolated victories — they were the through line of her life’s work: believing in what others overlooked. That same conviction would soon take shape again, this time on Third Street, in a little space called Gallery West.

Gallery West

Opening Gallery West on Third Street in Macon was also Kirsten’s idea — a way to extend the life of Kirk’s massive collection of portraits of musical greats spanning decades. After a couple successful summers selling his photographs at Jamband music festivals, Kirk spent three years digitally scanning his 60,000 photos while Kirsten planned what was meant to be a single pop-up exhibit for one holiday season.

That was ten years ago. It never popped down.

To this day, you’ll find Kirsten at her desk, surrounded by photos Kirk has printed and hung, or stacked in bins for easy flipping. She has the skills for running the gallery: business sense in the back office, warmth and wit out front.

The Gallery soon took on a life of its own, becoming another crossroads where Macon’s artists, musicians, and neighbors naturally gather. Much like she had done at the Big House, Kirsten helped create a space that drew people in — locals looking for community, musicians wanting to fellowship with old friends, and out-of-towners hoping to connect with the city’s creative pulse. The walls carry that energy, too, lined with original artwork by locals such as Johnny Mo and Kevin Scene Lewis, and photography by Bill Brookins and DSTO Moore.

“The Wests gave me one of my first chances to show my photography,” DSTO recalls. “I was still getting my name out there, and they opened their doors. I’ll always be grateful — and honored to call Kirsten a friend.”

Her loyalty to friends, community, and art itself has kept her rooted in the gallery. Much beloved is blues guitarist Robert Lee Coleman, a Macon native who helped pioneer funk and soul, and who mentored many young Macon musicians, including Southern Rockers. His guitar licks graced Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” and James Brown’s “Hot Pants,” and his influence continues to echo through the next generation of players he’s actively mentoring.

Kirsten and Kirk have long promoted Mr. Coleman and he has performed at the gallery. Their ongoing encouragement, along with Johnny Mo’s management of Mr. Coleman’s schedule, likely played a meaningful role in the recognition he received on August 15, 2025, when the Tubman Museum honored Mr. Coleman with its Legacy in Music Award, alongside Stax icon William Bell.

As their relationship with Mr. Coleman shows, Gallery West isn’t just a home for photographs or artwork. It’s a crossroad of legacy, active connection, and keeping art and music alive… a natural extension of the Big House.

Kirsten is preparing to retire from her daily gig at the gallery, although she’ll stay through the year for GABBAfest and Tedeschi Trucks Band show.

“Any time there’s a band-related event in Macon, we get so many fans coming through the gallery,” Kirsten says.

Among the treasures fans will find is a collection of vintage silver gelatin prints — living fragments of music history, developed by Kirk decades ago in his own darkroom. These signed, affordable prints capture an eclectic sweep: country legends like Merle Haggard and Hank William Jr., punk icons like The Clash and Elvis Costello, and intimate portraits of Dickey Betts and ABB moments stretching back to the ’70s. Just thumbing through them feels like time travel.

Once Kirsten steps back, the plan is for the gallery to remain intact as an art co-op, still carrying Kirk’s work alongside local artists while someone besides Kirsten manageas the day-to-day.

“I’m looking forward to not working for the first time in my life,” Kirsten tells me. She plans to root herself at her home in Shirley Hills, the house she fell in love with at first site which sits in the middle of wooded acreage.

Kirsten being Kirsten, though, she just might chose to work in the gallery one day a week… or more!

“I think planting a seed, something as simple as buying [the Big House], has created a lot for Macon,” Kirsten told Macon Magazine. “We’ve left our mark on Macon, and I’m proud of it.”

She should be proud. We know buying that house wasn’t simple. Or easy. Without her, there’d be no museum to walk through. No gallery to showcase Kirk’s photos. She kept the doors open and the crossroads humming. She made a home for Macon’s creative legacy, trading in and out of the driver’s seat with Kirk over the years.

Kirsten West with Col. Bruce Hampton — a larger-than-life character who wandered into the Big House mid-renovation as its very first guest. Known for championing the weird and wonderful, Hampton had once launched the Allmans at Piedmont Park in 1969 and later pushed Kirsten to manage a band he believed in. She remembers him as a dear friend to her and a mentor to musicians, able to spot greatness early, including in a 12-year-old Derek Trucks.

Originally published in Macon Magazine.

The Essential Force

The truth is, the ABB never could have kept its story alive without Kirsten partnering with Kirk. In a world of managers, promoters, and record men, she was something rarer: the essential force behind the scenes.

The work wasn’t just about saving a house, it was about who gets remembered and who gets written out. Most stories about Southern Rock spotlight the men, with guitars slung low, wild hair, messy geniuses. Women, when they’re mentioned at all, are usually cast in the margins: wives, daughters, girlfriends, cooks, housekeepers. But Kirsten was never content to stay in the kitchen or stand offstage. She always stood next to Kirk, but she stood as her own woman carrying a dual energy that defied categories; she was nurturer and doer.

Yes, she opened doors and welcomed people in, but she also had the gumption to shut doors when lines were crossed. Time and again, Kirsten showed she wasn’t just “keeping house” for Southern Rock or for Macon; she was making sure both endured.

Her role wasn’t feminine or masculine so much as essential. In a culture dominated by amplifiers and testosterone, Kirsten became the force that balanced welcome with discipline, and warmth with resolve.

She gave Southern Rock both its hospitality and its backbone.

Tending Macon’s Legacy

Kirsten moved to Macon in 1993, and then she bet on it. She rolled up her sleeves and set it on fire in the best possible way. She bought the Big House at a time when it needed a steward, not just an owner, and opened its doors wide enough for Gov’t Mule to play itself into existence in the Allman’s original practice room. She published Hittin’ the Note in its early years, setting the pattern for chronicling Southern Rock and Kirk’s adventures on the road with the ABB.

Alongside all that, she became a quiet matriarch to a traveling tribe of musicians. Her kitchen became a sanctuary, her house a waypoint, and now Gallery West is the active crossroad of Macon’s creative community.

In her words and in her work, Kirsten has helped carry forward Macon’s legacy as a place where art gets made and women speak their minds. She’s been right on time in a world that needs more women telling the truth out loud.

Shaping the City

It’s easy to romanticize Macon’s past. Kirsten chose to help shape its future, surviving literal and metaphorical ghosts. Through it all, she never stopped showing up. Because of her efforts, Macon is once again a gathering place for music lovers.

She’s lived many lives: At a desk on mahogany row, behind the curtain, inside the Big House’s renovation, at the printing press, beside the tour bus, and across the gallery desk. Through every incarnation, Kirsten listened to her inner voice — the one that told her to go to Hollywood, answer the classified ad, buy the house, open the gallery. And she’s still listening at 80.

Kirsten will tell you she never took a salary at Gallery West, and barely took a salary at Capitol Theatre. The money went where it needed to—toward the gallery’s health, toward keeping Kirk’s photographs in the light, toward the art, the music, and the people who walked through the door. That’s been her way all along.

If you ask her why she’s stayed in Macon all these years, she’ll tell you straight: it’s the people, the art, the music, the theater. She also loves her home in a forest, sharing her space with animals who wander the property. It’s the nature that feeds her soul — in the city she refuses to leave.

In the early years of the Big House, she wrote in Hittin the Note:

“I am constantly reminded that I live in a shrine to a band and their fallen brothers. I am married to a man who is driven to preserve every note they have ever played. I can't help but reflect on this fact and to be grateful that my life has been enriched not only by them and their music but by their fans as they wander through my life for brief moments as they pay tribute. We get lots of cards and letters from people thanking us for opening up our home as we do, but we really want to thank you all for being the kind of people that we would invite into our home.” — Kirsten West, Issue #15

Most people guard their homes like sanctuaries, bolting their doors tight. Kirsten not only opened her heart in generous words like the ones above, she also opened her front door. If a fan knocked, she let them in.

Over the years, 20,000+ people walked across Kirk and Kirsten’s threshold. Imagine that for a moment… 20,000 strangers coming to your door, not to borrow sugar, but to peer into your living room, to touch your walls, to feel the history. That kind of openness is rare. Extraordinary even.

That’s why when Kirsten steps away from the daily gallery work, her presence will remain in every corner of Macon she’s touched. Because the truth is, she’s isn’t just the Godmother of Southern Rock. She’s the quiet champion of Macon itself — the advocate who reminds us what’s worth saving and fighting for. She shows us what it means to plant roots and tend them for a lifetime.

Much of that legacy was built shoulder-to-shoulder with Kirk, but her light shines distinctly as her own. Her work carries her imprint, her steady insistence that Macon deserves more. If we pause and listen, we can plug into Kirsten’s lingering energy. It’s part of the city’s atmosphere now and forever.

Kirsten’s voice hasn’t dimmed at all and the projects keep tugging at her. That’s her gift: keeping Macon’s past alive and daring it toward a future that feels as soulful as ever.

Why Held Here

Kirsten West showed up in Macon and showed out, encouraging musicians and artists to think boldly, and a whole city to think twice before underestimating a woman with vision. She turned a historic house into a launchpad, a gallery into a gathering space, and a publication into a platform for voices that mattered, chronicling a musical force that still ripples today.

Fierce, fearless, and full of fire, Kirsten is the reason Macon’s story just keeps getting better.

With gratitude to Macon Magazine for first capturing some of Kirsten’s words in their 2025 Women’s issue (April/May) and Music issue (June/July), which helped inform this profile.

Macon is a city that wears its ghost stories proudly, and the Big House is no exception. Some say its halls hold more than memories — and the Macon Beyond crew dug into the tale in a special episode you can watch here on the Visit Macon site.

For Reddog

I’m dedicating this profile of Kirsten West — the woman who helped preserve the home and history of the Allman Brothers Band — to my dear friend Reddog, who passed away yesterday (September 16, 2025). Reddog, a blues guitarist, was the first to hear me stumble through “Blackbird” on guitar back in Atlanta in the ’80s and told me I was a natural. Just this summer, he emailed to say I was “on a roll,” inspiring him to jam in Pensacola and record in Muscle Shoals, while he inspired me to dig deeper into Macon’s music scene — even connecting me with Willie Perkins last year.

A lifelong Duane Allman fan, Reddog gently reminded me that the ABB weren’t just legends — they were real men who changed the world with their music — and that their fans deserve to see their story told with love. If I’ve managed to do that here, it’s because Reddog reminded me to, and reminded me who I am: a Cultural Storyteller who can shine a light on our heroes and help keep their legacies burning for those yet to come. There will always be creative people taking their spark from Duane and the Brothers — and Reddog’s own fire helped light the way. He can rest now, still with us in a way, knowing he’s keeping the circle unbroken.

About the Author

Cindi Brown is a Georgia-born writer, porch-sitter, and teller of truths — even the ones her mama once pinched her for saying out loud. She runs Porchlight Press from her 1895 house with creaking floorboards and an open door for stories with soul. When she’s not scribbling about Southern music, small towns, stray cats, places she loves, and the wild gospel that hums in red clay soil, you’ll find her out listening for the next thing worth saying.