John Stanley Killingsworth: Keeping Time, Coming Home

Held Here is a profile series highlighting the artists, archivists, entrepreneurs, and visionaries who have shaped Macon’s cultural identity. Each subject is someone who planted roots and, through their work and presence, has helped preserve the city’s creative spirit for the next generation.

This profile features drummer, songwriter, vocalist, and lifelong time-keeper Stanley Killingsworth. His six-decade loop from Dublin to Macon runs through Grant’s Lounge, Capricorn-era moments, protest marches, various local bands, and launching his son Tony Tyler into the biz. From pulling wagons loaded with gear as a boy to writing new songs today, Stanley has kept the beat for a scene and for Macon’s lineage that’s still very much alive.

Stanley Killingsworth:

The Beginning

That wide-open grin, the blond crew cut, the little bow tie… it’s pure Dublin-boy innocence long before he ever knew the beat would be his life’s compass. No one could have guessed Stanley would one day keep time for a whole community of musicians, including Gregg Allman.

Prologue — Boyhood

The security guard steps out of the booth, hand resting on his belt, squinting at the procession of white-shirted preteens pulling two wagons full of music equipment, rattling metal keeping rhythm with squeaky wheels.

Stanley Killingsworth pulls his Radio Flyer a few steps ahead of Tap Nelson as they all stop at the Veterans Administration hospital’s gate, a place that feels as off-limits as a military base and twice as solemn. The guard looks closely at the boys and the amps, cables, and microphone stands piled high and tied down with clothesline.

Four boys. Two wagons. One dream that’s just a little too big for Dublin, Georgia, in 1965.

“You boys know this is secured government property?” The guard asks, voice riding the line between suspicion and amusement.

Stanley straightens his shoulders, trying to show they belong. “Yes, sir,” he says. “In fact, my aunt works here. We’re going to play at a birthday party on the other side. Cutting through is faster, if you don’t mind.”

Tap and David stand behind him, matching white shirts crisp in the sun, “The Sterlings” stitched in silver thread on the pockets—a flourish courtesy of Tap’s mother, who believes in presentation even for eleven-year-old musicians. Behind them, Stanley’s brother Mike, their roadie by birthright, jams his fists into his pockets and waits for the verdict.

One long pause. One small miracle.

“Alright,” the guard says at last, waving them through with a half-smile. “Go on, then, but watch for cars.”

They roll forward as if crossing into foreign territory—quiet streets, brick buildings, manicured lawns—feeling like conquering heroes with wagons instead of horses. After today, the guards won’t question them again.

“We thought we had arrived,” Stanley says 60 years later, in 2025. “We were big time. A live band willing to go anywhere, however long it takes to walk our gear.”

And in the way that matters most at age eleven, they were big time. They may have been trying to “show out for the girls,” sure, but at heart they were true musicians—practicing in basements and double carports, worshipping the sounds of the ’50s and ’60s. The Beatles appeared on Sullivan only the year before, and suddenly every neighborhood in America was sprouting boys with guitars and backyard bravado.

For Stanley and the Sterlings, those wagons weren’t toys. They were tour vans, and every mile they walked across town was their first taste of the road.

In the beginning, those wagons got them everywhere they needed to be. But after a couple of years, the adults stepped in the way adults often do—quietly, practically, and with the sort of everyday support that becomes monumental only in hindsight.

First, the mothers took over, each driving her son and his gear to every gig. Then came the upgrade no kid could’ve predicted.

When the boys were around fifteen, Stanley’s uncle, Alton Killingsworth—who lived right across the street—offered them the use of the hearse from the Black cemetery he owned in East Dublin. It was a 1960 model: long, gleaming, and far too grand for a group of teenage musicians hauling amps across Laurens County. The boys didn’t have driver’s licenses, which didn’t stop them one bit.

“It was wild,” Stanley says. “Pulling up to a party in that hearse.”

And in its own way, these transportation assists showed just how much family—mamas, uncles, aunts—had been making the music possible long before the boys knew what a real music career looked like.

Stanley Killingsworth and Ed Grant Jr., photographed by Stanley’s wife Julie at the 2025 Macon Arts Alliance Awards.

More than fifty years after Stanley first walked into Grant’s Lounge on Poplar Street in Macon, Georgia, as a young drummer, Ed called him to share the Grant family’s spotlight — a full-circle moment between two old friends who helped shape the sound and future of Middle Georgia.

Photo by Cindi Brown

The First Spark — Dublin, Georgia, 1964

In the years when television shows were black-and-white and the names Fillmore East and Capricorn Studios meant nothing in Dublin, a nine-year-old boy sat cross-legged on pile carpet and watched the Beatles change the world. It was February 9, 1964.

Across America, kitchen tables went quiet. Teenagers forgot what they’d been told to do. And in one small Georgia living room, Stanley watched Ringo Starr behind his drum kit and understood something he hadn’t had words for yet: a shy boy could make a little noise and people will listen.

“The next day at school,” Stanley says, “everybody was talking about the four long-haired boys with drums and guitars, singing and shaking their heads in time with the music. I just wanted to be Ringo — and still do. It lit a fire and a dream in me that’s lasted a lifetime.”

In Dublin, music drifted off porches in the evenings and rolled out of Fords on Saturday drives, carried by AM static that softened everything it touched. Stanley’s mother, Lynise, kept Elvis records spinning on the turntable. His grandfather played a worn guitar on his farmhouse porch, the kind of music that wasn’t meant for applause—just company. His father, John, called Jack, was a builder who built them a large home and sometimes drove a school bus, and while he didn’t fully understand what Stanley was dreaming, he bought his son some drums anyway.

Stanley’s first kit came straight from the kitchen cabinet: pots, pans, and wooden spoons. He’d bang out patterns that made sense to him. Later in school, he found those little beats carried weight. “I saw how the kids noticed when I drummed on my desk,” Stanley says, “and so at recess I’d start singing to the beat and they were even more intrigued.” His early music-making efforts stopped some of the teasing he was used to and actually made the skinny redheaded kid seem a little cool.

Before he ever saw himself behind a drum kit, Stanley imagined he’d be a guitar player. As a boy, he stood outside the music store window staring at a semi–hollow body acoustic—the Big Kaye—until the longing practically etched into the glass. One day his father bought it and Stanley taught himself chords from books, studying diagrams and shapes, convinced this was his future. “But I soon realized guitar was a lot of work,” he says, laughing. “Compared to drums that are easier, where you just keep a beat.”

He’s wrong about drums being easy—at least for most people. Stanley’s rhythm was instinctual. The Big Kaye was played by his bandmates, but it quietly delivered its purpose: it helped him realize that guitar wasn’t his instrument.

Rhythm was and always had been. He just needed that little detour to see it.

Before drums fully claimed him, though, rhythm showed up in another unlikely expression: tap dancing lessons. Stanley’s parents signed him up with Miss Margaret Hill, whose dance studio sat behind her house in Dublin. His father loved to dance at local events, and figured his quiet son might find his footing there, too.

For months, Stanley practiced shuffles and ball-changes between two girls, one of them Tina Blankenship, working up routines for the big recitals. He expected to get teased at school—he was already used to being punched in the chest in the hallway by bigger boys—but something strange happened instead. When the school’s star athlete approached him after a performance, Stanley braced himself… only for the boy to straighten the sequined collar on Stanley’s costume and tell him he’d done a good job.

“I was surprised in a good way,” Stanley says. “It made me realize the world wasn’t just one way. There was good in young people.”

That unexpected kindness landed deep, becoming one of the early pivot points of his life. And when the day finally came that he no longer wanted to take tap lessons, he handled it in the most childhood way imaginable: he climbed a massive tree in Miss Hill’s yard and hid at the top until class ended. His parents didn’t fuss when he quit. He simply redirected all that rhythm back where it belonged—into making music.

Stanley soaked up everything his ears could catch: Elvis, the Beach Boys, and the crooners — Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Nat King Cole, Bing Crosby — “and on, and on, and on,” as Stanley puts it.

By nine, he’d formed his first band, The D.S. 2, with his best friend David Simmons, who played a banged-up four-string guitar. Stanley played bongos. Another kid added electric guitar. Nobody played bass because, as Stanley half-jokes, “no one wanted to play bass — and that’s still a problem.”

D.S. 2 played all over town — outside on air-conditioning units, under carports for neighborhood birthday parties, and in American Legion halls where they earned five dollars each. Sometimes, if luck was good, they got a slice of cake. There were no lessons, no sheet music. Just ears, hands, and the deep instinct that music was something to feel, not study.

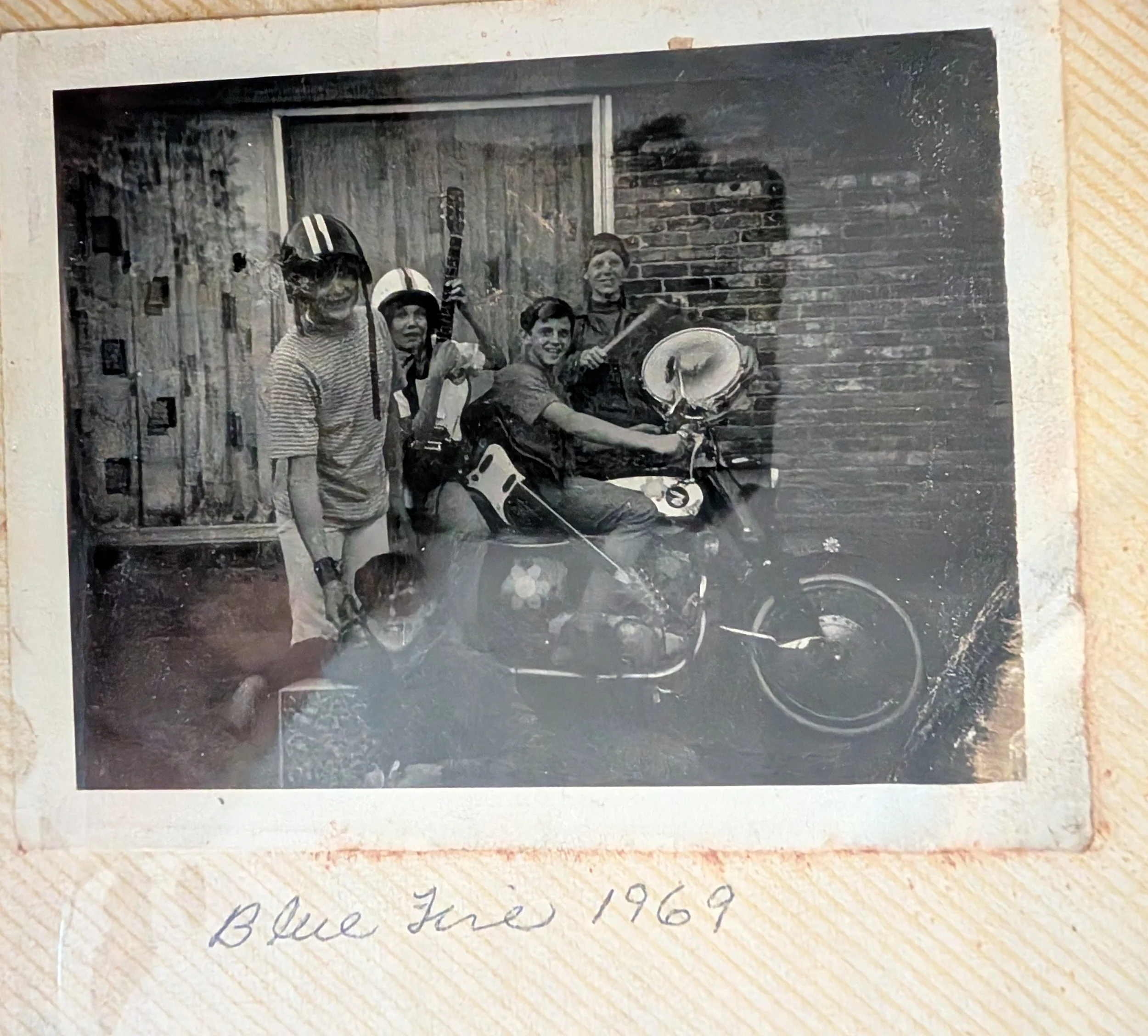

Blue Fire, 1969.

Thirteen-year-old Stanley stands in the back with his drum, Tap at the motorcycle’s rear. They played patios, birthday parties, and American Legion halls — and within a few years Stanley would be behind a kit at Grant’s Lounge. Every big story starts small.

The Ed Sullivan show awakened music in youth all across the U.S., and when the Fab Four appeared again on tv the following Sunday night, just one week later, Stanley’s fate was sealed. “I blame Ringo,” he says, laughing about his lifelong condition: incurable rhythm.

His teenaged aunt and uncle would come over, play records, and dance with his parents in the living room, “further feeding my beautiful disease,” Stanley says. He likes to point out that before the Beatles were the Beatles, they opened for Little Richard in Hamburg, Germany, giving Macon a shot of credibility as a music incubator, and showing the looping tie of musical influence between Macon and Liverpool.

Rhythm carried him through the long afternoons of adolescence, through those 45-rpm revolutions and into a decade that would make Georgia the unofficial capital of a sound—Southern Rock—that blended blues ache, gospel depth, and country storytelling into something new.

Stanley and his friend Milton “Tap” Nelson would play together in bands as kids, rotating players in groups with names like The Sterlings, Blue Fire, Our Heritage, and Cousin It and The Hairy Men. Tap soon got a copy of the Allman Brothers Band’s first album released November of 1969, introducing Stanley to their future, though neither boy had a clue of what was to come.

For a kid growing up in Dublin, it felt like the whole world was turning toward music. He didn’t know it yet, but Macon—the mighty little city just up I-16—would become his second hometown and his proving ground.

While Stanley’s world was expanding musically, the wider world was tightening politically, especially in the South. By the early 70s, Dublin was being pushed into a new era, and the shy redheaded kid who found his voice behind a drum kit was about to find his courage — and conviction — on a much different stage.

Growing Up in Dublin

Stanley grew up in a house his father built—large enough to echo, sturdy enough to feel permanent—and yet filled with the quiet that follows people who drink more than they should.

Both of his parents were high-functioning alcoholics. Most evenings, his father would retreat to the back room and pass out. His mother often drifted asleep on the couch. There was no shouting, no violence, no chaos—just an absence that settled into the walls.

His mother was a schoolteacher from LaGrange, Georgia, raised a block from the teaching college that shaped her life. She taught at a public school until the drinking caught up with her, then got sober, rebuilt herself, and found a new position at a private school. She played piano at home—soft, warm pieces that filled the rooms with gentleness—but never performed for anyone outside family or church.

“She was a sweet, sweet woman,” Stanley says.

His mother’s side of the family carried a story shaped by postwar ambition. Her father and brother opened a car dealership after WWII and became millionaires, the kind of quiet prosperity that changes a family’s trajectory. Her brother Jim Stanley went on to become second-in-command of the brand-new Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s drug division. Stanley was given his mother’s maiden name as his own first name—a nod to that branch of the family tree

His father had grown up in the Laurens County countryside on family land bordered by a wide pond on one side and a sprawling beaver dam on the other. The place remains in the family, and when Stanley was in his twenties and thirties, he and his bandmates rehearsed out there or played for family—music rising over the fields his grandfather farmed.

Jack wasn’t just a builder—he was woven into Dublin’s civic fabric. He was a Shriner who rode horses in parades, eventually upgrading to the biggest Harley-Davidson the dealership sold, leading processions with chrome and roar. He kept two horses behind the house, and every morning before school, Stanley and Mike fed and groomed them. Summers meant helping with their father’s construction jobs, digging footings in the heat and learning early that hard work wasn’t optional. In a family where the belt hung quietly in the background, you didn’t skip your responsibilities. You showed up.

It was a household held together from contrasts: the humble steadiness of his father’s people and the upward climb of his mother’s. Stanley walked both sides comfortably.

The family’s circumstances were comfortable enough that they employed a Black housekeeper, as his mother’s family had. Stanley grew up seeing Black adults treated as part of the household rhythm, not as “others,” and absorbed early that people were equals… long before Dublin’s institutions caught up to that truth.

His younger brother, Mike, followed a different path from music. He went to Georgia Southern, became a banker, and later worked for the Florida bank that helped launch The Villages. Stanley tried to teach Mike the bass as a boy, but “he didn’t have it,” Stanley says with a grin.

Meanwhile, Stanley’s own path kept circling back to music.

But before Macon ever entered the picture, there was one night when the restlessness nearly carried him beyond the Georgia state line.

Stanley was sixteen, still figuring out the world, but already consumed by a feeling he couldn’t name—only that it was bigger than Dublin, bigger than high school hallways and church gigs. One night, after his parents had gone to bed, he packed a bag, slipped out to the carport, and slid behind the wheel of his mother’s brand-new Buick Skylark. He was headed to California.

He didn’t know where exactly. Didn’t have a plan, but was going anyway.

He eased the car out of the driveway and went to his girlfriend Marie’s house, to say goodbye. Something she said that night made him stop.

“Marie talked me out of it,” Stanley says. “And I’m so glad she did.”

Within a few months, life would accelerate—Marie’s pregnancy, his decision to drop out of school, the long days of work—and the unexpected phone call from Ed Grant Jr. that would bring him to Macon. Turns out the start of his music life was waiting just up I-16, with a neon sign over the door that read: Grant’s Lounge, not out in California.

Early on, when still pulling their gear in wagons, Tap’s mother had gotten the boys a gig inside the VA hospital auditorium. To their young eyes, the stage felt grand and cavernous, making their childhood band suddenly look like something bigger. It was their first taste of what a real room could do to a kid with drums and a dream.

All of it—the quiet house, the kind mother finding her footing again, the equality he took for granted, the family land, the VA gig, the early encouragement—formed the foundation for the boy who would soon march, play, protest, love, and stand firm.

And yet Dublin has never really left him.

Stanley watches the nightly 6 p.m. news on Macon’s WMAZ, Channel 13, and the station’s weather camera—mounted on the tallest building his Uncle Alton once owned downtown—shows him a live view of Dublin where he grew up.

Every evening, he sees the long stretch of main street where he and his classmates once marched toward City Hall; the steeple of the church where his daughter Michelle got married; the old movie theater with its marquee still intact, the same one where his mother dropped him off on Saturdays to watch westerns and cliffhanger serials with his friends.

There’s something quietly poetic about Dublin showing up in Stanley’s living room every night, steady as the weather report, reminding him where his story began.

The Line in the Sand

By 1971, Stanley at 16 was all elbows and drum sticks, navigating Dublin on the edge of an era about to snap. The Civil Rights Act was no longer an idea — it was a mandate — and Dublin responded the way many Southern towns did: by building a brand-new high school for the sake of integration.

The building was shiny and modern with a long, curved drive, but the hearts filing into it were anything but aligned.

Black students, whose old school sat on the Southside of town, had been promised combined mascots and school colors, but that promise evaporated within weeks. Black students protested each morning along the school’s circular drive, chanting, refusing to let the injustice pass quietly. Most white students walked on by.

Stanley and a few of his white friends decided to fall in beside their fellow Black students, not out of bravado or politics, but because it’s wrong to ask one group of students to sacrifice everything while the other loses nothing.

For their trouble, Stanley and his friends got punched in the hallways, pushed, called names, had books slapped out of their hands, and worse of all, received death threats phoned to their homes late at night.

“I didn’t run,” Stanley says of getting death threats. “I didn’t even think about stopping. You don’t back off when the cause is right.”

Marie — whip-smart, pretty, the kind of A+ student teachers brag about — talked easily with Black students, including boys, and then two teachers pulled her aside to say, “Your father wouldn’t want you talking to those Black boys.”

The tension bled into the streets with Blacks marching against inequality and police overreach.

Stanley and his bandmates started going to the Southside of town, slipping into nightclubs and makeshift stages to hear Black musicians play the kind of soul they couldn’t find on their side of town. In one club, they watched a vocalist they called the Black Elvis, a man whose voice poured into the room like honey warmed over fire.

“He was a beautiful man,” Stanley says. “We wanted soul in our music. We were white and you could hear it.”

They rehearsed with Black musicians and played at The Shanty on the outskirts of downtown. They learned phrasing and restraint — things that can’t be taught in words, only absorbed by proximity.

Meanwhile, the marches continued. Crowds walked from the Southside, crossed the railroad tracks, and headed straight into downtown toward City Hall. Stanley walked with them, shoulder to shoulder.

One afternoon, he walked beside a Black girl from school. As she slipped out of her shoes, Stanley reached to carry them for her, and that’s when a police cruiser crept up beside him. The officer behind the wheel stared at him with a hatred so concentrated it felt radioactive.

“If I’d moved over a few inches,” Stanley says, “that man would have run over my toes.”

The cop followed them, shadowing the march, the weight of his stare cold enough to leave a scar. At sixteen, Stanley learned what hate looks like up close.

During another march, cops picked up Stanley, William, and another friend — all white — and took them into the bowels of City Hall. They made the boys call their fathers. Stanley’s dad simply said, “I’m not coming. He knows the way home.” The other boy’s father arrived and immediately began beating his son, with the cops watching for a moment, then intervening.

“I’d been raised by the belt, judiciously,” Stanley says, “but I’d never seen a dad fight his kid in public. The pressure was on everyone.”

In the marches, older Black men gave instructions to the crowds before each walk. One day, the leader gestured toward a small cluster of white teenagers — Stanley and his friends — and said: “Brothers and sisters, I want to introduce you to some of our blue-eyed soul brothers.” It was the first time Stanley felt claimed by a tribe beyond his own.

This moment is still clear to Stanley, and it’s where music and morality became welded in him. By the end of the year, the school finally mixed the colors and the branding. But the cost had already been paid — in bruises, in threats, in hours walked under hateful gazes.

And in something else, too: The shaping of a musician who still stands with whoever is right. When the music world in Macon soon cracked open before him, he stepped toward it with the steadiness of someone who had already learned what it costs to stand for something.

Finding a Door in Macon

By the end of the 1960s, Macon was the crossroads where soul, gospel, and rock-n-roll met and shook hands, sometimes grinning and sometimes clinching teeth. As Stanley points out, Little Richard’s wild shout had paved the way. Otis Redding’s voice still hung over the city like smoke from a late-night fire. And Phil Walden, Frank Fenter, and Alan Walden at Capricorn Records had transformed a sleepy Southern town into a mecca for musicians creating that hybrid sound—the place where the old South met electric guitars and came alive.

The still-unknown Allman Brothers Band went up to Atlanta to play in Piedmont Park on the weekends. Fourteen-year-old Stanley and his best friend, sixteen-year-old William Chamblee, drove up in 1969 to hear the Brothers and other “killer rock bands, mostly from Florida” rip through the humid air. One of Stanley’s favorite groups back then was Boogie Chillin’ fronted by Macon vocalist Asa Howard — a band that had its own loyal following before the ABB rolled into town and changed the landscape.

Stanley was eager to attend every live show he could find in those years, not just the Macon legends. Once, when he and a group of friends went to see Led Zeppelin, they arrived early and couldn’t figure out how to get inside the venue. In true teenage logic, they simply wandered around back.

There, to their astonishment, was Led Zeppelin’s road crew unloading equipment. Instead of shooing the boys away, the crew put them to work — handing them cases, pointing them toward the loading ramp, letting them carry gear inside like honorary roadies.

“We didn’t know any better,” he says. “We were just trying to get into the show.”

It was classic Stanley — too earnest to be a nuisance and just lucky enough to be welcomed into the machinery of the music he loved.

At 15, he and his buddy William drove to Macon from Dublin — on a learner’s permit, no less — to see the Allman Brothers Band at the Coliseum. Cowboy opened the show, but when the Brothers took the stage, the room warped.

“You could feel everything rearrange itself,” Stanley says. “Like the molecules moved.”

He can still see it—the drum set angled at forty-five degrees, Jaimoe adjusting the kit like a man tuning the weather, Gregg sauntering out to the B-3, and then Duane, electric and alive, plugging in and hitting the first notes of Midnight Rider.

“They were like gods,” Stanley says. “They were bringing a whole new genre to the world.”

Stanley also remembers exactly where he was when he learned that Duane Allman was gone. He was working for his father then, driving a two-lane stretch from Milledgeville to Dublin on a freezing cold night. He’d borrowed an Army coat from a friend — one of those heavy green ones that fell almost to his ankles — and cranked the heat against the dark.

The AM radio was his only company, all static and soul, when the DJ cut in with the news: Duane Allman had died in a motorcycle crash in Macon.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Stanley says. “It was like somebody saying your own brother had died.” He pulled the truck onto the shoulder and started pounding the steering wheel, the cold pressing in through the glass.

In the years that followed, he’d feel Duane’s absence and presence in equal measure. Stanley jammed several times with Jaimoe and Dickey Betts at the Red Lamp Lounge in the old Dempsey Hotel, just blocks from where Duane had made his name. Those nights were loose and electric — the music chose the direction and everybody else just hung on for the whole ride.

“Playing with Jaimoe and Dickey,” he says, “it was like being plugged straight into that current Duane started.”

Stanley didn’t know it as a kid chasing live performances, but his own path was already bending toward that same light in that same place, just a few blocks over. It had started with him playing a private event at Grant’s Lounge in 1971, when Duane Allman and Berry Oakley were still alive. Two years later, he’d get the call that would change everything.

At seventeen, working alongside his father at a prefab housing plant in Fort Valley, Georgia, Stanley’s phone rang. On the other end was Ed Grant Jr.—the young heir of Grant’s Lounge, Macon’s first integrated music venue. Ed was putting together a new band with Tap Nelson and David Coleman and needed a drummer. Tap suggested Stanley, would he want to join them?

Stanley didn’t hesitate, even though he had quit high school, married, and had a baby on the way.

That single invitation carried Stanley out of Dublin and into Macon’s musical bloodstream.

Stanley in his element at Grant’s Lounge — the legendary Macon club where Ed Grant Jr. first put him onstage, setting him on a path that wound through five decades of music and friendships.

Grant’s was a crossroads, a sanctuary, and sometimes a powder keg. Ed Grant Sr. had literally mortgaged the family home to open that little club on Poplar Street — a Black-owned bar where white and Black musicians shared the same stage in an era when it had only recently been against the law for them to gather at all. Inside, the rule was simple: if you could play, you belonged. It was a quiet act of defiance, a living rebuttal to everything the South had tried to keep separate.

Less than a decade after the Civil Rights Act, Black and white musicians were still rarely seen sharing a stage in Georgia. But at Grant’s, the music mixed before the culture did — a little room that would soon be known far beyond Macon as the original home of Southern Rock. Teenaged Stanley may not have fully understood the weight of it all at the time. He just knew this might be his chance to make music his living.

Macon was still carrying the old scars. Restaurants that quietly refused service, radio stations that divided playlists by color, the sideways glances that told you change had come on paper but not in practice. And yet, inside Grant’s, you could see the future sweating it out under the stage lights. Black and white musicians shared mics, swapped solos, and traded jokes between sets. In a South still learning how to look at itself in the mirror, Grant’s became a mirror of another kind — reflecting what Macon could be when the groove took over.

For Stanley, playing there was a gig and an unspoken lesson in what courage and community sound like. He was barely old enough to vote, but when he sat onstage behind that kit for the first time, he joined a lineage that stretched from gospel tents to Southern rock arenas.

“Grant’s Lounge,” he says today, “was where everything began and everything came back around full circle.”

That call from Ed Grant Jr. was an anointing, even if Stanley couldn’t see it then.

Clubs, Legends, and Luck: The Scene

To understand Macon in the early seventies, you have to imagine a city sweating music from every pore. There was always something playing — onstage at the Douglass Theatre, in Wesleyan College’s auditorium, from jukeboxes in diners where the eggs never cooled. At night, the rumble deepened, and you could follow it downtown to the tight glow of Third Street. There, the doors of Zelma’s club New Directions swung open while Grant’s Lounge around the corner was pumping.

Grant’s wasn’t polished. It didn’t need to be. The paint was chipped, the lighting uneven, the stage just high enough to give the musicians a little lift. But it was the kind of place where you could see and hear everything that mattered about the South’s new sound. On any given night, you might hear the same vibes that ran through the Allman Brothers, Marshall Tucker, Wet Willie, or a young Tom Petty with Mudcrutch.

Stanley was new to Macon, bringing his drumsticks and that stubborn joy he’s never outgrown. He had joined Moon Dawg — a name that sounded half bluesman, half cosmic — with Tap Nelson on guitar, Ed Grant Jr. on keys, and David Coleman on bass. He and his young wife, Marie, were already parents to their daughter Michelle, and Stanley had made Marie a promise: if he hadn’t built a real place for himself in Macon’s music scene by the time Michelle started school, they’d pack up and go back to Dublin. That gave him five years to make good on every dream he’d ever knocked out on a kitchen pot.

Good thing Stanley and the Moon Dawg crew were young and raw… and fearless. Mr. Grant Sr., who ran the place with an old-school mix of order and warmth, mentored them. He let the boys rehearse upstairs in the empty rooms above the club.

And downstairs? The night belonged to Grant’s. People danced close, drank hard, and let the music undo their burdens.

Then came the night in 1973 when the god walked in.

The band was halfway through a set when the room started to stir — heads turning, whispers rippling like wind through a wheat field. Mr. Grant Sr.’s voice boomed from the PA: “Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Gregg Allman would like to come up and play with the band.”

The crowd erupted. Gregg crossed the floor slow and confident, long blond hair flowing, leather coat brushing his knees, tall boots clicking like a midnight riders’ spurs.

Stanley, behind the kit, froze.

“He was a THE guy from THE band” he laughs. “I thought, Mr. God, Sir, we are not worthy!”

Gregg smiled that half-smile, the kind that made everyone else exhale. He picked up Tap’s guitar — a cheap one, strings a little high, frets a little worn — and asked, “Y’all know Crossroads?” They did, and the room caught fire.

“Between verses,” Stanley remembers, “he’d step back and retune the guitar while we kept playing. Then Gregg said, ‘Let’s do Jelly, Jelly, Jelly.’ We didn’t know the song, it hadn’t even been released. He just said, ‘Play it like Stormy Monday, without the fast part in the middle.’ So we did. And he sang his ass off.”

For Stanley, that might have been a brush with fame, but Gregg didn’t arrive like a celebrity; he arrived like a fellow laborer who understood that music was work and wonder at the same time. It’s easy to mythologize Macon’s golden era — the gods walking amongst men, the records pressed, the legends born — but for musicians like Stanley, it was simpler and harder than that. It was about keeping the beat steady while the world shifted around him. About finding his place in the musical community and a way to support his family.

When the gigs at Grant’s wrapped for the night, there was always another door down the street to push open — The Red Lamp Lounge in the basement of the old Dempsey Hotel, where the air smelled like bourbon and brass, or Zelma Redding’s New Directions, at 533 Third Street, a powerhouse of a club run by a powerhouse of a woman.

Zelma opened New Directions in the 1970s as her own literal “new direction” after Otis Redding’s death — stepping into the business world to honor her husband’s legacy and to build one of her own. The room seated 350 and pulsed with the kind of energy Macon lived on back then: tight bands and the anticipation of something important about to happen.

It was in that room that Zelma’s sons Dexter and Otis Redding III took their first steps into music as Father’s Pride, before later becoming The Reddings, joined by their cousin Mark Locket. For young musicians like Stanley, walking into New Directions meant stepping into the Redding family’s influence where Otis’ voice and Zelma’s leadership guided the place.

Zelma didn’t stop there. She ran her own booking agency and record store in the 1980s, shaping Macon’s music community from the front office and the backstage. She and her legacy are still alive today, and her daughter Carla Redding-Andrews now leads the newly opened Otis Redding Arts Center, carrying forward the family’s mission to educate and cultivate young artists.

Carla was even present at the recent Macon Arts Alliance Awards, where she presented an Otis Redding Foundation award to Mike Mills of R.E.M., who grew up in Macon. That same night, the Grant family was recognized, gathering all the threads of Macon’s music history in the same room, nodding to one another.

One night at New Directions, Joe English — the easygoing drummer who lived on the Allman Brothers’ farm in the mid-70s and would soon be recruited by Paul McCartney to join Wings — called Stanley over, “Mind taking the chair while I finish my drink?”

Stanley laughed and said, “I’m not a jazz drummer.”

“Just keep it light and expressive,” Joe replied. So Stanley did — one song, then another, until he realized Joe wasn’t coming back; he was too busy working the ladies at the table.

“I played all night,” Stanley says. “Guess I’m a jazz drummer after all.”

Moments like that are what made the Macon scene what it was — unplanned, open-hearted, unpretentious. Nobody asked for credentials. The only question was, Can you play?

The Band Years — Almost Capricorn

By the mid-seventies, the rush of Grant’s had become a current that could carry a young musician anywhere. Every week someone new was being talked about — the next big thing, another band Phil Walden might sign.

When Ed Grant Jr. took a job on the road, Stanley did what every working drummer does — he looked for a new gig.

Before that next Macon chapter took shape, Stanley slipped back to Dublin and into the quiet world of small-town recording rooms, where musicians learned to work fast and get it right on the first take.

He cut tracks at Gil Gillis’ studio, a modest but reliable room where local gospel groups, R&B singers, and country pickers all came to make something permanent on tape. Not long after, he began doing session work for Mr. Lovett, a South Georgia studio owner who later moved his operation to Augusta, Georgia. Lovett ran the kind of studio where a drummer needed to be steady, versatile, and unflappable — three things Stanley already excelled at. “I think I was a session man for him,” Stanley says. “He kept calling me, anyway.”

Those Dublin sessions — along with the influence of Johnny Fontaine, who moved in the same circle — sharpened Stanley’s instincts long before he ever set foot in Capricorn Studios. They taught him how to serve a song and hold his nerve while the red light was on.

By the time Macon called again, he was ready.

It came from a pair of brothers already wrapped in legend: Tim and Greg Brooks. Tim was a guitarist whose playing could part the air; Greg was a singer with a voice full of pain. Their music was a mixture of blues muscle and Southern gospel hope, and for a while they looked destined for the big time. Capricorn Records had them in its orbit.

Stan joined the Brooks Brothers in 1974 and found himself in the most combustible mix of talent he’d ever known. He soon learned that genius and gentleness don’t always share the same body. Tim Brooks was enormous — six-foot-six, four-hundred-plus pounds, with hands that could coax melody or mayhem from a guitar.

“Tim had a heart as big as his frame,” Stanley says, “but he also had anger management issues …” The band’s rehearsals were as unpredictable as the weather in August. One night, they’d be swapping riffs and laughing; the next, they’d be nursing bruises and making up over beers.

Years later, Alan Walden pulled Stan aside at a Big House show and confessed, “You know why Capricorn didn’t sign y’all? We were scared of Tim’s temper.” Stanley shrugged then, but the truth hit him deep. They’d been that close — one decision, one misbehavin’ away from the contract that might have rewritten his life.

Stanley’s stretch with the Brooks Brothers — center, Tim on guitar, Greg on vocals — remains one of the strongest bands he ever played with. Capricorn Records showed interest, and for a moment, the next chapter seemed ready to break wide open. (Stanley is on the right.)

It would’ve rewritten Kyler Mosely’s life, too. Back then, Kyler was working closely with Tim and Greg, running sound, hauling gear, keeping bands together through sheer heart and hustle — long before he became President of GABBA (the Georgia Allman Brothers Band Association) and one of the anchors of Middle Georgia’s musical memory. Kyler would go on to help organize the Skydog festival from its start in 2006, carrying the ABB torch into the next generation.

Still, Stanley doesn’t tell that near-famous story with bitterness. He tells it like describing a thunderstorm that passed over his house and split his favorite tree but left the roots alive. What stayed with him wasn’t Tim’s mental instability that ended their chances, or even the ache of almost-fame. It was the friendship that survived the chaos.

“We were brothers,” he says simply. “We bled a little, but we still played together. And Kyler’s still around, too — keeping the ABB sound going.”

That’s because brotherhood sometimes meant taking the hit and showing up anyway. Once, when Tim’s temper flared at Stanley, his brother Greg tried to step between them. The punches that followed left Stan with a sore neck he still jokes about. “I ducked, but not fast enough,” he says. Then, as always, he grins. “I wouldn’t recommend joining a band. But I wouldn’t trade it, either.”

The gigs kept coming — a smoky blur of bars and dancehalls across Georgia, the van heavy with gear and laughter. One night at Grant’s, a patron told them, “When y’all finish up here, come on by the studio.”

Early in the morning, they found themselves at Capricorn Studios, where the real alchemy happened. They piled in, still smelling of sweat and cheap beer, and walked into history. Producer Johnny Sandlin was at the console, spinning reel-to-reel tape from Gregg Allman’s Laid Back sessions.

“Johnny played us the outtakes,” Stan remembers. “Just us players standing there, and he’s smiling like we belonged.”

Those late-night moments taught Stan that the line between myth and man was thinner than he thought. In the South, fame and familiarity coexisted in the same room, shared the same ashtray. You might back your van into the same loading dock Duane once used and never know it until the janitor told you.

When the Brooks brothers’ band finally dissolved, the dream didn’t disappear; it just changed shape. Tim and Greg kept playing until their deaths in 2015, three weeks apart. The news hit Stan like a cymbal crash. “Two brothers gone almost together,” he said quietly. “They were thunder, man. The kind that rolls for miles.”

Those years also brought Stanley back into old musical circles. His 1970s band Southfield — made up of Chip Vandiver on guitar, Ken Wynn on guitar, Steve Myers on keys, Kenny Walters on bass, and Paul Long on vocals — had opened a Christmas party for Stillwater in Warner Robins on December 23, 1976, capturing the night on a reel-to-reel deck with two mics set out front. The tape vanished for more than thirty-five years, only resurfacing recently, a time capsule of Stanley’s young hands keeping time for a hungry band in their prime.

Decades later, Southfield regrouped at Paul Hornsby’s Muscadine Studios in Macon — the same room where Hornsby shaped so many Capricorn-era classics. Chip Vandiver came up from Florida, Paul Long stepped to the mic again, and Kemper Watson held down the bass. Stanley sat behind the kit, older now, but still thumping. “We stepped back into our own story,” he says.

Southfield, Stanley’s 1970s band that once opened a Stillwater Christmas show, pictured here in a later reunion. Ken Wynn, Chip Vandiver, Steve Myers, Kenny Walters, and Paul Long all found their way back to the music — with Stanley behind the kit, still thumping, still home.

Stanley, his son Tony Tyler, and a handful of other players also recorded at Muscadine during Tony’s rise — another chapter in the father-and-son arc that kept winding its way through Macon. Different rooms, different decades, but the same rhythm connecting them all.

Looking back, he sees that whole chapter as a proving ground. Those years gave him scars and stories, yes, but also an understanding of rhythm that had nothing to do with tempo. It’s not the speed or volume that matters, Stanley believes, it’s how the drummer stays and holds the line when everything around them starts to break apart.

That lesson became his compass. It carried him through the lean years, through marriage and divorce, through the endless small-town circuits that make up the working musician’s map.

Detours and Doing Fine

By 1978 the golden spell was breaking. Southern Rock, that swaggering blend of blues, country, and gospel heat, had burned through a decade of glory and excess. Macon’s sidewalks were stilled as the stars scattered. Capricorn’s lights were dimming, and across the South, mirrored balls were replacing Marshall stacks.

“Disco,” Stanley says, wrinkling his nose. “The D-word.”

For drummers like him, disco was a reminder that eras end. Clubs that once smelled of amplifier dust now glimmered with strobe lights. The four-on-the-floor beat marched in like an occupying army. “It wasn’t personal,” he admits. “It just didn’t need us.”

An early snapshot of Stanley behind the kit, after Disco — the dreaded D-word — swept through Macon and sent him searching for stages elsewhere.

So he did what grown men with families and calloused hands have always done in the South when the world tilts: he went to work.

Stanley had promised his wife that if the music hadn’t taken off by the time their daughter Michelle started school, he’d bring the family home to Dublin and give the child a normal life. When the calls slowed and the crowds thinned, he knew it was time.

“I kept my word,” he says. “I owed Marie that much.”

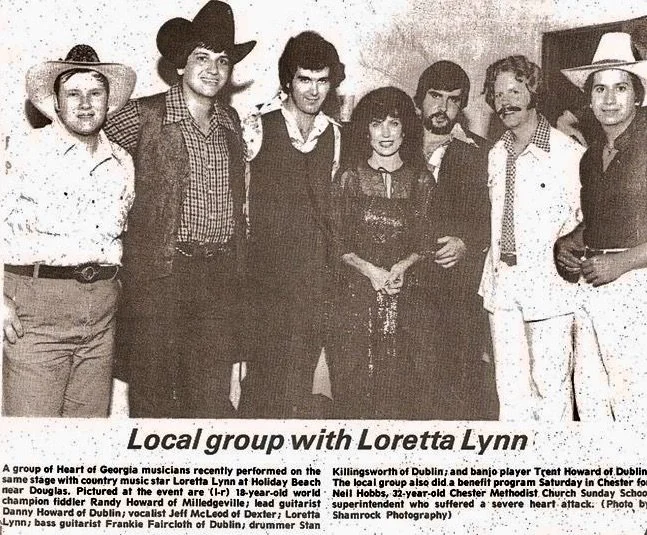

Back in Dublin, he joined a country band called Rocky Creek—a good outfit with tight harmonies and pressed shirts. They played VFW halls, county fairs, and a few stages grand enough to make a man straighten his collar. One night in Douglas, Georgia, they opened for Loretta Lynn. “We were just proud to warm the air before she sang,” he says.

A regional all-star lineup — Randy Howard (fiddle), Danny Howard (lead guitar), Jeff McLeod (vocals), Loretta Lynn, Stan Killingsworth (drums), Trent Howard (banjo), and Frankie Faircloth (bass) — gathered at Holiday Beach near Douglas, Georgia, for a special show that brought a young Dublin drummer into the orbit of a country music icon — an early high-water mark of Stanley’s playing career.

When the gigs thinned again, he shifted from rhythm to square footage, starting a floor-covering business that would anchor him in Dublin for the next decade or so. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was steady—another kind of craftsmanship. The business grew as he worked with builders in three states. “I went out and measured homes for flooring,” Stanley says.

One of those jobs came from a friend whose name is familiar to anyone who’s ever read liner notes on a Southern rock record: pianist Chuck Leavell. Before Chuck became the Rolling Stones’ longtime touring keyboardist and current musical director, he was the young prodigy who helped define the Allman Brothers’ sound on Brothers and Sisters. By the time Stanley was laying floors in Dublin, Chuck was a tree farmer with his wife on their property between Macon and Dublin.

“I did Chuck’s floors,” Stanley says with a grin. “When he called, I showed up.”

Later, Chuck had a small studio in his backyard, and Stanley found himself recording there. One evening he took a break from drumming and stepped out into the night. Looking up toward the back of Chuck’s house, in the lowing light, he heard voices and saw cigarettes glowing between fingers. The accents were British.

Slowly, Stanley realized it was Mick Jagger and Keith Richards chatting up the hill.

The Rolling Stones were in town working at Chuck’s studio, although Chuck was out of town. There they were, not on a stadium jumbo-tron, but on a back porch in Middle Georgia. Stanley thought briefly about asking for an autograph, but decided to play it cool.

“Chuck’s my friend,” Stanley says, “and I didn’t want to upset him by bothering his guests.”

Then Stanley put out his joint and went back to his session.

It’s a small story, but it says a lot: even when he’d traded the road for a tape measure, Stanley somehow kept finding himself in the rooms where the big stories were happening, quietly doing the work and staying himself.

By the 2000s he was financially secure for the first time —a drummer turned tradesman who’d managed to make good on both sides of his promise: a roof for his family and a constant beat under the surface.

Stanley (center) during his years with Mainstreet, a local Dublin band that captured the spirit of its era — shiny shirts, big hair, and musicians who stayed booked and busy. Stanley fit right in: dependable, adaptable, and always in the pocket.

Even then, the music never truly left. He kept writing songs. And to this day he can’t go for more than a few minutes without singing out loud to whoever’s around. If a phrase in conversation reminds him of a lyric, he’ll start singing—his own tunes, a Beatles riff, maybe something Gregg once played. It’s not performative; it’s reflex. The man talks in melodies.

“Sometimes I’ll be telling him something serious,” says Julie, his current wife, “and he’ll just slip right into a song. I can’t even stay mad—it’s like the music’s got first rights to his attention.”

He played Friday and Saturday nights in smoky southeast Georgia bars, the kind where the jukebox leaned slightly left. He’d finish a carpet installation on Friday afternoon, wipe the milling from his hands, and head straight to the gig, playing with various bands he’d start, such as The Clue, Cross Fire, or Midnight Bluez.

There’s something Southern about that balance—the notion that work and art can coexist without apology. In a region where most dreams are carried in pickup trucks and paid for in cash, Stanley had found a way to honor both the muse and the mortgage.

He says those were good years. His daughter Michelle grew up to sing in her church; his son, Tony, inherited his syncopation. He started to understand what all those years in the spotlight had really been about. The need to simply play. Whether laying tile or laying down a groove, the goal was the same: keep it even, keep it true, make it last.

Family Rhythm

Rhythm, for Stanley, is inheritance. It’s what his grandfather played on an old country guitar after long days in the fields, what his mama’s fingers coaxed from piano keys. His father wasn’t a musician, but he understood timing in his own way—driving bus routes, managing schedules, manufacturing homes, keeping people moving in the right direction. “Guess I got both sides,” Stan says. “The beat and the business.”

When his daughter Michelle was born, he and Marie named her for a Beatles song—“My Michelle”—because, in his mind, every joy needed a soundtrack. “She can really sing,” he says with quiet pride. “Church stuff mostly.” She stayed close to Dublin, raising her own family, her life steady where his was restless. He loves that.

But it was his son, Tony Tyler, who caught the fire. “He got bit,” Stanley says. “I saw it happen.”

Tony was eight when his father started taking him to Capricorn Studios. While Stanley recorded in Studio A, Tony spent hours in Studio B—playing in the stair well, drumming on the furniture, talking to the engineers. “He just absorbed it all,” Stanley recalls. “Couldn’t stop him.”

Perhaps the ghosts of studio B got into Tony’s bloodstream.

As Tony got older, the stakes grew. Stanley remembers driving Tony and a small group of musicians to Johnny Sandlin’s famous Duck Tape Music studio in Decatur, Alabama — a legendary homegrown room in the back portion of Johnny’s house. “It was all for Tony’s music,” Stanley says.

They were working with a songwriter from California — the ex-wife of a former member of Chicago, of all things — a pairing that felt unlikely and yet perfectly fitting in Stanley’s world, where the right people always seemed to cross paths at the right time.

Duck Tape had that Sandlin warm-reverb magic: wood-paneled walls holding a hush that caused musicians to sit up straighter. For Stanley, recording there with his son felt like standing at the intersection of two eras — Capricorn’s past zinging through his veins and Tony’s future zipping out of the monitors.

Tony was also shaped by the musicians in Stanley’s orbit — the ones who kept the Middle Georgia sound alive long after Capricorn’s heyday. One of the most influential was Eddie Stephens, a veteran guitarist and songwriter from the powerhouse Midnight Bluez Band, a group that dominated the regional circuit for years. Everyone in that band wrote, everyone contributed, and Eddie’s songs became part of the working musician’s songbook across Georgia.

Tony recently re-recorded Eddie’s tune “Tough Luck,” giving new breath to a song that had been part of the local vernacular for decades. Stephens is now with Nitebird, but his fingerprints remain on the whole region, including on Tony’s musical DNA.

That’s how lineage works here: songs get passed down and carried forward.

By the time he was thirteen, Tony and his father were onstage together, like two heartbeats running parallel. “Double drummers,” Stanley says proudly. “He could already read my mind. I’d lift my shoulder, and he’d know where we were going.”

Eventually, Tony learned to play guitar, bass, keys, and sax—anything with strings or sound. By the late ’90s, Stanley built a new band around him called The Tony Tyler Trance, a father-and-son outfit that toured Georgia’s backroads for nearly a decade. “He was just a kid,” Stanley says. “We’d play Friday and Saturday nights in the bars, then he’d go to school Monday morning.”

There’s a tenderness in Stanley’s voice when he talks about those years. He knows not every child survives their parent’s dream. “Most musicians don’t want their kids to follow in their footsteps,” he says. “It’s too rough. But Tony… he never really had a choice.”

And Tony proved it—a full-time musician in St. Petersburg, Florida, who once played with Melody Truck’s band, now living the road life his father once led. “He’s playing for a living,” Stanley says. “Never had a job that wasn’t music. I’m proud of that.”

These days, Julie keeps Stanley steady, grounding him the way a bass line grounds a melody. They met in a Warner Robins bar called Cricket’s Lounge in 2008—Stan playing, Julie listening, both of them orbiting the same familiar Southern soundtrack. “I think she loved the music first,” he jokes. “Then she figured I wasn’t so bad either.”

They enjoyed a friendship before things turned romantic.

Julie grew up in Arkansas, a lifelong music lover with a knack for keeping things organized—a rare gift among artists and dreamers. She was a mortgage officer during her career and now acts as secretary of the Community Of Older Music Professionals (COMP), where she’s become both crossing guard and mission control for Middle Georgia’s talented, seasoned musicians and industry professionals. The group meets monthly and boasts members such as former ABB road manager Willie Perkins, members of the band Stillwater, and other local bands from Capricorn’s hey day.

Stanley admits Julie has to scold him sometimes when his humor veers into mischief.

“Stanley loves to make jokes,” she says with an affectionate sigh. “Most of them are ridiculous.”

He grins, unbothered. “Somebody’s gotta keep things interesting.”

Their marriage works because it’s built on rhythm too—give and take, sound and silence, knowing when to solo and when to stay in the pocket. “I’d be lost without her,” Stan says. “She keeps me tuned.”

Together, they’ve created a gentle second act—a life where music still fills the air, but the pressure to “make it” is gone. When they sit on the porch in the evenings, the world slows to a tempo that suits them.

“It took me a long time to realize,” Stanley says, “success ain’t always about who’s listening. Sometimes it’s about who’s still there when the song ends.”

Stanley at Skydog75 in 2021, joined by GABBA President Kyler Mosely and Sister Teresa from Daybreak — a trio that captures the festival’s soul. Though he didn’t play this year, Stanley’s history with the event runs deep and he plans to play at next year’s Skydog80, the festival’s 20th anniversary honoring Duane Allman, and being held over two days for the first time ever: Nov. 21 & 22, 2026.

The Brotherhood and the Beat Goes On

Stanley is still writing songs that sound like sunlight breaking through Spanish moss—Southern, soulful, and stubbornly alive. He can’t stop, after all. Songs come to him during the day and the night, and he must capture them in the moment, or they’ll float away.

He doesn’t hear every instrument when he’s composing; he doesn’t try to. “I give the musicians some direction and then wait to see how they want to add their own riffs,” he says. For all the years he’s led bands — from the early days to his current John Stanley Band — he insists the writing itself is the easy part.

Most musicians don’t write for money anyway. They write because they can’t not write, because the melody keeps tugging at them. “People think the money’s in songwriting,” Stanley laughs. “It usually goes out faster than it comes in.”

“Studio time isn’t cheap,” Julie says, “and most musicians put their money back into the music, wanting to get their sound on tape.”

Stanley jokes that he’s “recorded more songs than he can remember,” and he isn’t far off. A couple of years ago, he and producer Rob Evans spent weeks inside Capricorn Studios, recording 104 tracks—everything from raw blues to roots-rock sermons. They made some of those songs into two albums and left the rest for later, a kind of time capsule waiting to be rediscovered. “Some of ’em are outtakes,” Stan says. “But they’ll get their turn.”

His two albums are on Spotify, where Tony will continue to add more of those songs.

He’s proudest of his song “The Miracle of Love,” written for World AIDS Day in Washington, D.C., in 1993. He won the contest and flew there to perform it on the steps of the Capitol—his first time on an airplane. “I met senators and strangers,” he says, “and I thought, Well, Lord, look at me now—this redheaded boy from Dublin, Georgia, standing in D.C. singing about love.”

Stanley (far right) in Washington, D.C.: his original song “The Miracle of Love” was for the national World AIDS Day ceremony. He performed at the Department of Justice for advocates, policymakers, and families affected by the epidemic — a moment he later called the highlight of his musical career. The Dublin Courier-Herald featured the story on its front page, recognizing how a small-town songwriter carried a message of compassion onto a national stage.

He keeps a small notebook on his table at home, scribbling down lines when inspiration hits. He can feel a song arrive, like somebody whispering in his ear, but if he doesn’t write it right then, it’s gone. He can’t chase it. Just has to wait for it to circle back.

That acceptance—that patient, weathered grace—is what defines him now. He’s not fighting time anymore; he’s collaborating with it.

And when he says writing songs non-stop is aggravating, he means that they keep coming so fast he doesn’t have time to share them with his band, so they can work out their parts, learn the song, perform it, and perhaps eventually record it. A song captured on paper can feel like a waste when it’s not known, loved, and played by musicians. It’s like a coin burning a hole in his pocket.

But the road hasn’t always been lined with music. One night after a show at Grant’s Lounge, Stanley was assaulted in a downtown parking lot by two unidentified men who had been drinking at a nearby country bar. He recalls almost nothing of the encounter except the sound of loud voices approaching and, later, a bite mark on his left forearm, proof he was able to fight back a little. He returned to his RV, unaware of the extent of his injuries, and went to sleep.

He woke to a phone call from Ed Grant Jr. asking if something had happened, the owner of several local buildings had heard of a disturbance. Only then did Stanley notice blood in the bed. Police and EMTs arrived, and he was taken to the hospital for evaluation. During that exam, doctors discovered a tumor on his eardrum—an unrelated but potentially dangerous condition that might have otherwise gone undetected.

“It took something bad for them to find something worse,” Stanley says with his trademark humor.

Grant’s staff reacted strongly. One of the security guards, seeing the blood on Stanley’s face, insisted the assault was unacceptable and vowed the men wouldn’t return. According to Stanley, they never did. And they were never caught.

Stanley Killingsworth behind the kit at Grant’s Lounge during the 2017 tribute shows that followed Gregg Allman’s passing — answering Ed Grant Jr.’s call to honor the man who shaped a generation of Macon musicians.

The incident is an example of the hazards that accompany late-night gigs, but it also revealed the strong community that surrounds Stanley. Julie returned early from a trip to Little Rock to care for him, friends helped retrieve his gear, and Grant’s kept an eye out for him in the weeks that followed.

What mattered was the way he got through it and fought through the tumor treatment — and the way Julie fought beside him. She kept track of appointments, medications, instructions, and moods. She kept him steady when he was scared, present when he felt foggy, and hopeful when the nights felt long. “She pulled me through it,” Stanley says.

The tumor didn’t stop him, but it changed him. It made the music feel even more precious—every clean hit of the snare, every melody that found its way into his notebook. And it sure didn’t dull his sense of humor. Stanley cracks jokes as often as he breaks into song, and if you’re not prepared for it, you’ll end up laughing yourself breathless at whatever unexpected one-liner he drops next.

Julie might shoot you a look that says don’t encourage him, but it never works. Stanley’s wit is too quick, too playful, too joyfully out of left field not to laugh.

The normal memory issues of aging now mean a word might escape Stanley occasionally. Julie helps him keep track of the details—song lists, set times, rehearsal dates. And when frustration flickers, she grounds him with a look or a word.

And then there’s COMP, where Stanley fellowships with local musicians who’ve known each other and played in various bands for decades.

Tim Griggs, who leads COMP and has watched generations of musicians move through Macon’s scene, puts it simply: “Stan is the complete package as far as music is concerned — a singer, songwriter, and musician. He also has a quirky sense of humor. It’s hard not to smile when Stan is around.”

Coming from Tim — an entertainment lawyer at Capricorn who doesn’t hand out praise lightly — it’s the kind of affirmation that lands true.

For all his musical seriousness, this is the Stanley most people know: goofy, generous, and happy to make himself the joke.

COMP meets once a month—men and women who wrote songs, sang, played instruments, engineered sound, hauled equipment, managed record labels, or covered the music industry. And still might. There’s teasing, tall tales, and the kind of shorthand that only comes from playing the same stages and surviving the same heartbreaks.

Stan still performs—sometimes solo, sometimes with the John Stanley Band, sometimes just him and a handful of COMP friends outside Fresh Produce Records for First Friday in downtown Macon. Julie gets credit for arranging all of those COMP performance opportunities.

A lively First Friday outside Fresh Produce Records on Cherry Street, arranged by Stanley’s wife Julie: The John Stanley Band and other COMP players rotating through, sharing the sidewalk, drawing a crowd, and proving again that Macon’s music community is strongest when it shows up together.

Even after the Covid pandemic shut down the clubs, Julie and Stanley found a way for him to keep playing. With the help of local business owner Dr. Kris Ellis, they turned the empty fenced-in patio beside the Bearfoot Tavern on Second Street into what they lovingly called The Cage — a makeshift stage under the Georgia sun. For three and a half years, it became their refuge, and sometimes reunion of his band Southfield.

“The Cage was the best venue ever,” Julie says. “We didn’t have to deal with owners or curfews or any of that. We just showed up and played.”

The neighbors came. Strangers walking by wandered in. Kids danced. Musicians drifted through. It wasn’t about money anymore — it was communion. “We played for love and for tips,” Stanley says, laughing. “But mostly for love.”

The Cage finally wound down when the Social Duck build-out was complete, so the owner of Bearfoot Tavern asked Stanley and his crew to become the Bearfoot’s house band — a gig they happily held for two years. They might still be there if the building hadn’t suffered a massive roof collapse. Repairs have stretched on for years, but rumor has it the place is gearing up to reopen soon. If it does, Stanley just might find himself back in that corner again, sticks in hand, ready to time-keep another chapter.

Stanley with Dave, Ken, and Kenny at “The Cage,” the no-frills backyard venue where the band played for three and a half years — for tips, for friends, and mostly for the joy of it.

Now, when he walks through Macon’s downtown—past Grant’s Lounge, past the renewed Capricorn studio—he knows his story is part of the larger song. He’s not the headline, but he’s in the harmony.

And in his own way, he’s still teaching, still shaping. Younger musicians have cut their teeth playing alongside him and under his wing through all iterations of his bands over the years. Guitarist Travis Denny, from Warner Robins, joined Stanley’s band as a teenager, soaking up every gig. He took lessons from Stillwater’s Mike Causey, then carried that lineage forward; today, Travis is living in Nashville and making a living as a songwriter.

Adam Gorman started playing with Stanley when he was just fourteen. Now he’s a member of End of the Line, an Allman Brothers Band tribute outfit keeping that catalog alive for new crowds. Adam performed at the 2025 Skydog79 festival in Macon’s Carolyn Crayton Park (formerly Central City Park).

“The young people remind me why we start doing this in the first place,” Stanley says. “You get to pass the torch, but you also get a little of their fire back.”

Stanley doesn’t leave home as often as he once did. “But if playing is involved,” Julie says, “he’ll make his way there.”

That’s the truth of it— a drummer who’s seen the peaks and the pits and kept the rhythm anyway, with Julie by his side.

Stanley and friends playing at “The Cage,” the open-air, no-rules spot on Second Street where they played for the pure joy of it—no middleman, no cover charge, just music drifting into the sparkling Macon night.

Playing Through the Divide

When Stanley looks back now, he understands more clearly what those early years at Grant’s Lounge meant — not just for his career, but for the South itself. Playing in a band with Ed Grant Jr. wasn’t labeled “integration” back then; it was simply friendship, belonging, and the stubborn faith that music could bridge what the world insisted on separating. They didn’t set out to make history, only harmony. But sometimes those two things walk in together.

That truth stretched across decades, sometimes quietly, sometimes with a ring of the telephone. Because whenever Macon needed its music to matter, Ed always called Stanley. First for the music in 1973, when he invited a young drummer into the most courageous room in the South. Then for the memory in 2017, asking Stanley’s ABB tribute band, Soulshine, to bring the sound home to Grant’s just after Gregg Allman passed. And finally, for the Macon Arts Alliance honor ceremony in 2025.

That last call came because Ed wanted Stanley in the room, at the ceremony — as part of the Grant family story Ed and his sister Cheryl were about to lift into the light. When Ed stood onstage to accept the honor, he turned his own moment of recognition into a tribute to Stanley, closing the circle in a way only time can teach.

“So today I accept this honor on behalf of my father, my mother, Rosalee, my sisters Cheryl and Gaynell, and every artist… with special recognition to Mr. Stan Killingsworth standing in the back, thank you for keeping the music alive in Macon. God bless you all, god bless Macon, Georgia.”

The room erupted. Stanley pointed toward Ed and smiled, calling out, “You’re the man.” The applause swallowed his words, but the meaning carried, clean and true: fifty-two years later, they were still showing up for one another.

That exchange — one Black man, one white man, two old friends whose lives had moved through the same music and same spaces— was proof that the rhythm they shared in that tiny club on Poplar Street had outlasted the world that once tried to keep them apart.

Macon has changed since those days, though maybe not as fully as it should have. The lines are blurrier now, the stages more open, but the city still wrestles with its dual identity — birthplace of multiple American genres, yet shadowed by the questions of who got credit, who got paid, and who got left outside the door.

Stanley’s memories of Grant’s are nostalgic and also his own personal testimony. They remind us that music has always been the South’s most honest truth; the one place where people could stand shoulder to shoulder before much of the world was ready to follow.

When Ed Grant Jr.’s words filled the Mill Hill Arts Center that night, Stanley didn’t think about the past so much as the rhythm still running through it, and pushing him forward— the steady backbeat of friendship and the music that refuses to fade.

That’s what Stanley’s songs, including his latest “The Brotherhood,” have always been about: not a single band or a single moment, but the chain of influence, starting with the Beatles and running through Southern rockers, a beat that keeps drawing people together, no matter how many years have passed or how many miles sit between phone calls.

Stanley is also waiting for his new song “Full Circle” to download into his brain, tracing the loop of his life in music—from pots and pans in Dublin to late nights at Grant’s, from loading Led Zeppelin’s gear to watching his own son take the stage. If “The Brotherhood” is about the shared lineage of Southern rock, “Full Circle” will be his personal ledger: the ways the road bent, snapped, and somehow still led him back again to play on that same small stage on Poplar Street.

The John Stanley Band at Parish on Cherry Street, 2018. One of the countless Macon gigs where Stanley and friends like Tim Duffy on keys and Mike Fordham on guitar showed up, played hard, and lifted the room — the heartbeat of a working musician’s life.

Songwriter’s Showcase at Grant’s Lounge

Rain had been drizzling off and on most of the afternoon, turning the sidewalk into a mirror. Then—right on cue—a double rainbow rose over Macon, stretching from Mercer’s hill to the river’s bend. You could almost believe it was meant as a marquee: the show’s still on.

Grant’s Lounge has always breathed like an old bellows—pulling in night air, pushing out stories. That air carries half a century of smoke, laughter, and spilled beer, all of it soaked into the wood grain. When Stanley stepped through the door and onto the stage, the room recognized him—one of its own coming home.

Jeremy was sweating over the flat-top, cooking up the $5 “1971 Special” dinner. Somebody at the bar offered a taste of Grant’s homemade pork rinds, swearing it was gourmet. He was right.

My friend Susan and I drifted along the Wall of Fame—hundreds of photos of faces that never quite left the room: Duane, Percy, Etta, maybe even the ghosts of those who almost made it. Local artist Johnny Mo’s careful touches are everywhere, keeping the soul of Grant’s intact and giving the club just enough polish to shine under the low bulbs. Muralist Michael Pierce also added his swatches and signatures to the walls.

Mr. Grant Sr.’s portrait above the stage, painted by local artist Kevin Scene Lewis, is a soft-eyed guardian watching over the music he made possible. His presence seems to hold the stage in place.

Caleb, the sound engineer, was bent over the cables, coaxing the hum out of the monitors. He’s part priest, part mechanic, guiding the room into tune. That same corner of the room—where a seventeen-year-old Stanley once kept time in 1973—seems to vibrate from the past. If you close your eyes, you can almost hear the laughter from the night Gregg Allman dropped in and tilted the whole room on its axis.

On this night, the crowd was small—nearly a dozen of us scattered at metal tables and along the bar—but loyal and lean-in close. This wasn’t an audience you had to win over; they’d already come for the music, ready to listen.

Julie led Stanley to the kit like she does when the stage is dark, guiding him through the tangle of cords and shadows. Once he was seated, you could feel it—the room enlarging, time flattening out. The same hands that once pounded the skins at seventeen now rested on the sticks like old friends. There’s reverence in that.

It’s only the second week of Grant’s new Songwriter Showcase Wednesdays, and Julie at the mic introduced him as Stanley Killingsworth—though across the years some folks have called him Stan, or a few John because of the John Stanley Band. Julie jokes she can tell when someone met him by which name they use. In truth he’s all of them: the kid behind the kit… the man still receiving melodies…and the musician who put his own name into his band so he’d never forget what started it all.

“Tim Duffy is on keyboard and backup vocals,” Julie said to the sparse gathering. “These songs were recorded at Capricorn and they’re available on Spotify under the John Stanley Band.”

Stanley cleared his throat, tapped his sticks, and eased into “Sweet Surrender,” a tune shaped in a hard season and carried forward from it. Tim joined in. Fifty-four years vanished since Stanley first played that private party at Grant’s. Somewhere in the mix, you could hear the old room smile and breathe.

Stanley smiled, too, and leaned toward the crowd. He’s an introvert who comes alive behind his drum kit. His wavy hair, still a sun-washed strawberry blond, caught the stage light. The drumsticks in his hands were worn smooth from years of steady work, each nick and groove a road map of the places Stanley has been.

Julie hit “Play” on the video camera and sat back in her chair. The sound rose and fell with the rhythm of breath, or a bellows. When those chords rang, the past and present blurred.

Music filled every corner, richer than two men should’ve been able to make. Tim Duffy’s keys shimmered, and Stanley’s voice—clear, unguarded, carrying the years —rose above it. He can still hit the high notes, still bend a lyric until it feels lived in. The sound of a man bringing his own music to the stage that once gave him someone else’s. In fact, he sounds a bit like Gregg Allman. There’s poetry in that—he used to keep time for other people’s dreams; now he’s keeping it for his own.

Stanley didn’t stack his song list at random. Each song introduced by Julie carried a piece of the long loop he’s been traveling, and together the songs trace the shape of his life in Macon.

After “Sweet Surrender” came “Time Is a River,” a turn back toward Dublin and the boy he used to be. It carries memories of his childhood friend Tap Nelson, the guitarist now deceased who pointed Stanley toward Ed Grant Jr. and opened the door that led him to this very stage in 1973. Every time Stan plays “Time is a River” at Grant’s, Tap stands in the room again, just beyond the edge of the lights.

“Sacred Ground” followed — his nod to the Grant family and to the people who keep the lights burning for live music in Macon. Macon’s music story is all about how folks show up for one another, sometimes for decades like with Ed and Stanley. This song lands right at the center of that truth.

Stanley and Tim closed with “Tribe of Mankind,” a call for people to set grudges aside and meet on common ground. Not a sermon, just a hope set to melody. Stan has seen enough to know how easily people can be divided, and how much richer life feels when we all stay connected.

Four songs, each one circling back to something that made him who he is — the illness he pushed through, the friendships that shaped him, the town that adopted him. And beneath it all, the quiet belief that music can bring people closer. Playing these songs at Grant’s, on the same stage that gave him his first shot more than fifty years ago, pulled the loop tight.

The room and Stanley were breathing together again, the way they used to.

Stanley and Tim Duffy prepping to share four original songs at the Grant’s Lounge Songwriters Showcase, October 2025 — a full-circle night bringing Stanley back to this stage 54 years later to show just how much he still has to say.

As the songs wound down to a hush, you heard the clink of a glass, the creak of a chair, and then—applause. It wasn’t wild or rowdy; it was reverent. The kind that means people heard you.

The television above the bar played a silent ’70s horror movie, but even that felt right—every era layered together, 1973 brushed shoulders with 2025. Grant’s has never really left one decade before entering the next. It’s a living time machine, and the mystery isn’t in what’s changed, but in what refuses to.

When Stanley and Tim were finished, the applause may not have been thunderous—but it was true. That small crowd knew what it meant to watch a seventy-year-old drummer sing his own songs on the same stage where his seventeen-year-old self once learned to dream.

“We kept playing music,” Stanley says of himself and his cohorts from those early Capricorn days, the ones who are gone and the ones who are still around, still itching to play, still having much to contribute.

“We kept playing music because we couldn’t stop.” And they’re still at it.

For a man who’s spent his life keeping time, Stanley had finally arrived at the sweet spot between past and present—the downbeat of gratitude.

He’s still here, still bringing something alive that started long before most of us were born. Grant’s, bless it, is still listening 55 years later.

And in Stanley’s voice, you can hear the boy who dreamed of drums as a way forward, and the man who learned they were his way home.

Why Held Here

Stanley Killingsworth is Held Here because he’s spent a lifetime showing up and keeping the beat onstage. He marched when it was dangerous, played as often as he could, kept everyone laughing, and quietly raised the next generation of players like his son Tony Tyler and the other young guns who came up under his wing.

In the tree of Southern Rock — ABB at the trunk, national branches fanning outward — Stanley stands firmly at the base: one of the deep, old roots that steadies everything above it. His story comes full circle; it loops from Dublin’s wagon trails to Grant’s Lounge to Capricorn Studios and back again, proving that Macon’s music history is in the legends on the wall and also in the hands still playing. And the fellowship still growing.

About the Author

Cindi Brown is a Georgia-born writer, porch-sitter, and teller of truths — even the ones her mama once pinched her for saying out loud. She runs Porchlight Press from her 1895 house with creaking floorboards and an open door for stories with soul. When she’s not scribbling about Southern music, small towns, stray cats, places she loves, and the wild gospel that hums in red clay soil, you’ll find her out listening for the next thing worth saying.