Kyler Mosely: A Life in Macon Music

Held Here: Presence in Profile is a series highlighting the artists, archivists, entrepreneurs, and visionaries who have shaped Macon’s cultural identity. Each subject is someone who planted roots and, through their work and presence, has helped preserve the city’s creative spirit for the next generation.

This installment features Kyler Mosely, President of GABBA and one of Middle Georgia’s most devoted listeners. From his home in Lizella — where the Allman Brothers Band once rehearsed in the woods — to rehearsal rooms, radio studios, and festival stages, Kyler has spent more than five decades absorbing music until it took up residence inside him. Songs, sessions, lineups, and voices live in his head (and heart) the way records live on a turntable — spinning, crackling, ready to be dropped into conversation at any moment.

Kyler Mosely was just a kid when the Allman Brothers Band (ABB) first started practicing out at the now-famous cabin in Lizella, Georgia, west of Macon. He didn’t have to be inside the cabin to hear it; the sound of those guitars carried down the power lines that cut a pipeline through the pines. The hum of Duane’s slide and the thunder of Butch and Jaimoe’s drums echoed through the woods and rooted themselves in the bones of every kid within earshot, including Kyler.

Especially Kyler.

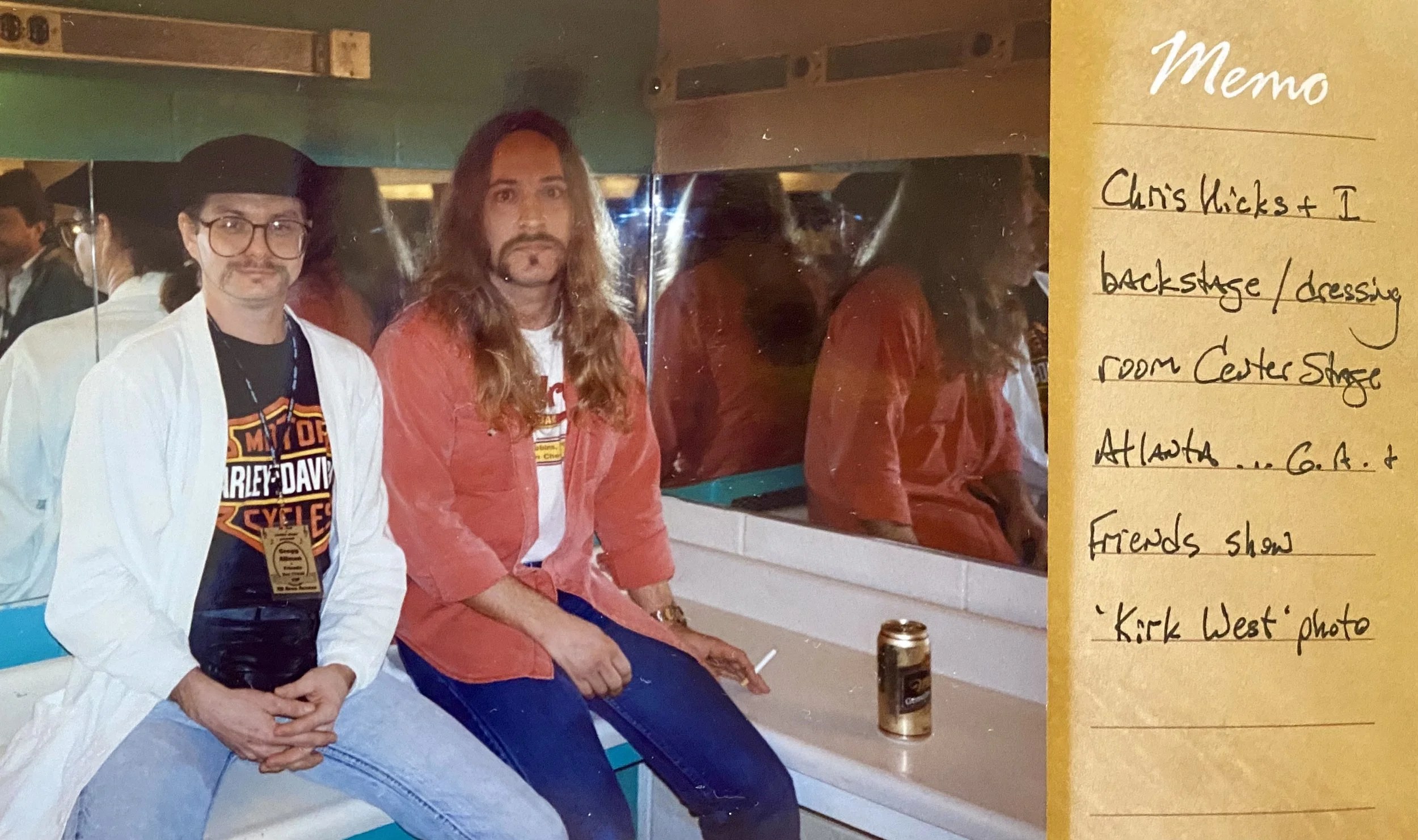

Lizella’s always been thick with musicians — back then and even now — but when the ABB came along, they lit the whole countryside on fire. Local pickers like Chris Hicks, now with the Marshall Tucker Band, started tuning in and stepping up, especially after getting a call from Jaimoe to come jam with the ABB.

A handful of Macon bands got caught in the crosswinds, including Boogie Chillun’, who were the local act before the Allmans rolled into town. “Those boys were hot,” Kyler says, “but then the ABB showed up, and the whole world changed.”

Even so, Boogie Chillun’s legend didn’t fade out (they opened for the ABB at least once) it just settled into the soil.

Kyler grew up hearing stories from the older guys, the ones who’d played with Boogie Chillun’ or snuck into their gigs. Names like Doug Miles and Asa Howard come spilling out of him like coins from a slot machine — who played where, who sat in with who, which bar, which night. Doug and Asa are still around, too, and still revered. But Kyler knows more than just about Boogie Chillun’; he’s a one-man encyclopedia of Macon’s musical DNA.

Kyler Mosely’s Early Years

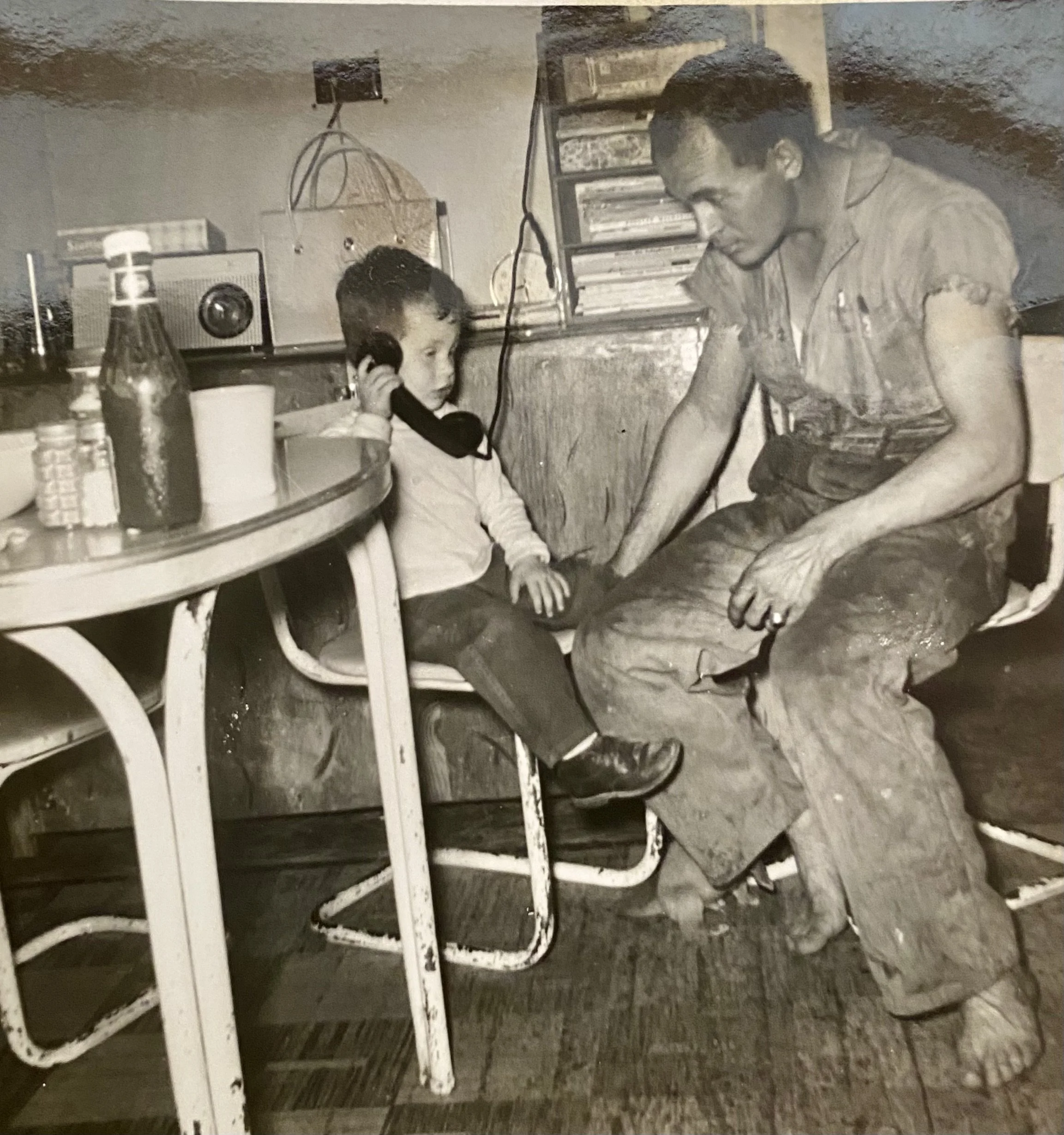

Left to right: A Christmas visit with Santa; Kyler at home with his father, L.G.; and a formal childhood portrait—already dressed for the world he was growing into.

As a teen he’d travel to Atlanta to hear players from Macon and other spots north, absorbing every detail and often recording the sets on his Nakamichi deck — the gold-standard machine that 70s and 80s musicians and engineers swore by for its clarity and fidelity. Kyler still owns that same recorder today.

Over time, that ABB sound and Southern Rock grew into something larger than any one band. Think of it like a tree: the ABB at the trunk, the national touring bands out on the branches, and down at the base, a homegrown root system of musicians, families, crew, and die-hard listeners who stayed close to where it all started and kept it alive. Kyler is one of the steady roots in that ground.

At 66, he’s still in the thick of it — not just as a walking encyclopedia, but as a living part of the story. He’s President of the Georgia Allman Brothers Band Association (GABBA) and has been a member from the group’s start 32 years ago.

As a young man, his family’s garage hosted enough jam sessions to qualify as a satellite branch of Capricorn. Tim and Greg Brooks rehearsed there, fine-tuning their sound under Kyler’s careful ear.

Kyler knows who’s related, and how, and he knows every name, every lineup change, and every late-night jam that’s ever mattered in Georgia. But while his title as President of GABBA might make him sound like a gatekeeper of ABB lore, his heart beats just as hard for the ones who never got a record deal with Capricorn— the hometown heroes, the sidemen, the bar-band philosophers.

“The ones Phil and Alan didn’t sign,” he says with a grin, “they interest me just as much, or more, than the bands who were signed.”

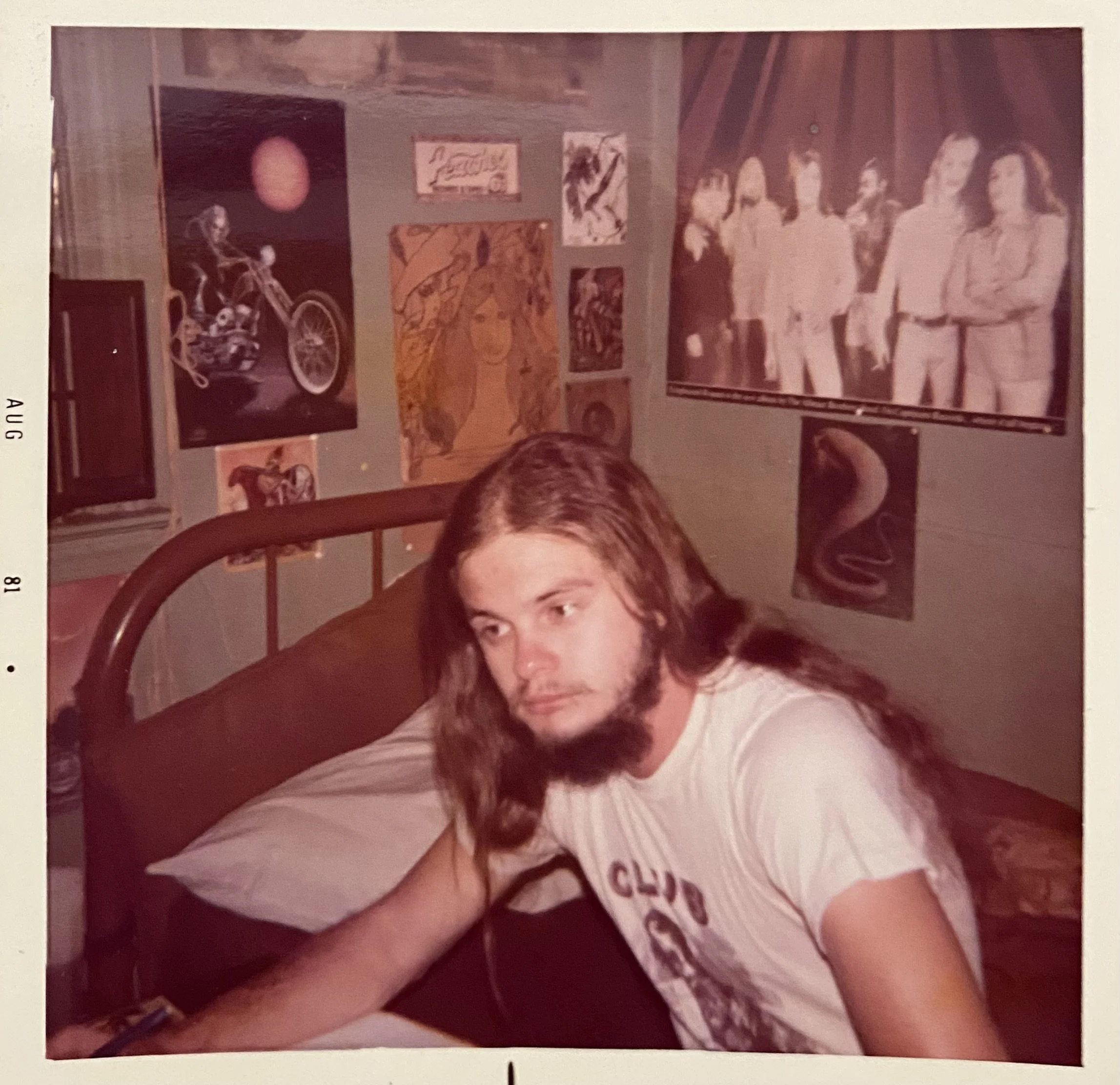

Early scenes from Kyler Mosely’s life:

A teenage bedroom lined with Southern rock idols and a Christmas moment with his brother Dale.

Home in Lizella, Georgia

Ask Kyler where he’s from and he’ll point to Lizella and the land around it; a map he’s memorized from childhood romps and bike rides, where creeks meet dirt road, where a cousin’s or uncle’s house once stood, where his granddaddy’s house still stands next door, where his dad wrecked the family car.

Kyler’s family has been in Lizella since the early 1800s, and you can feel it in the way he talks — slow but sure, his words shaped by a lifetime of belonging — of growing up in the fold of family who’ve lived side by side for seven generations, where every story circles back home. There’s a country rhythm to his speech, filtered through that long white beard, every syllable measured and deliberate. When he gets going on a story, though, the sentences tumble quick and sure, like he could catch the whole history of Middle Georgia before it slips away. He sounds like Lizella — humble and full of history.

He and Chris Hicks grew up within shouting distance, and somewhere along the way, their family lines tangled together. “We’re kin somehow,” Kyler says, the way Southerners do when blood and names start blending.

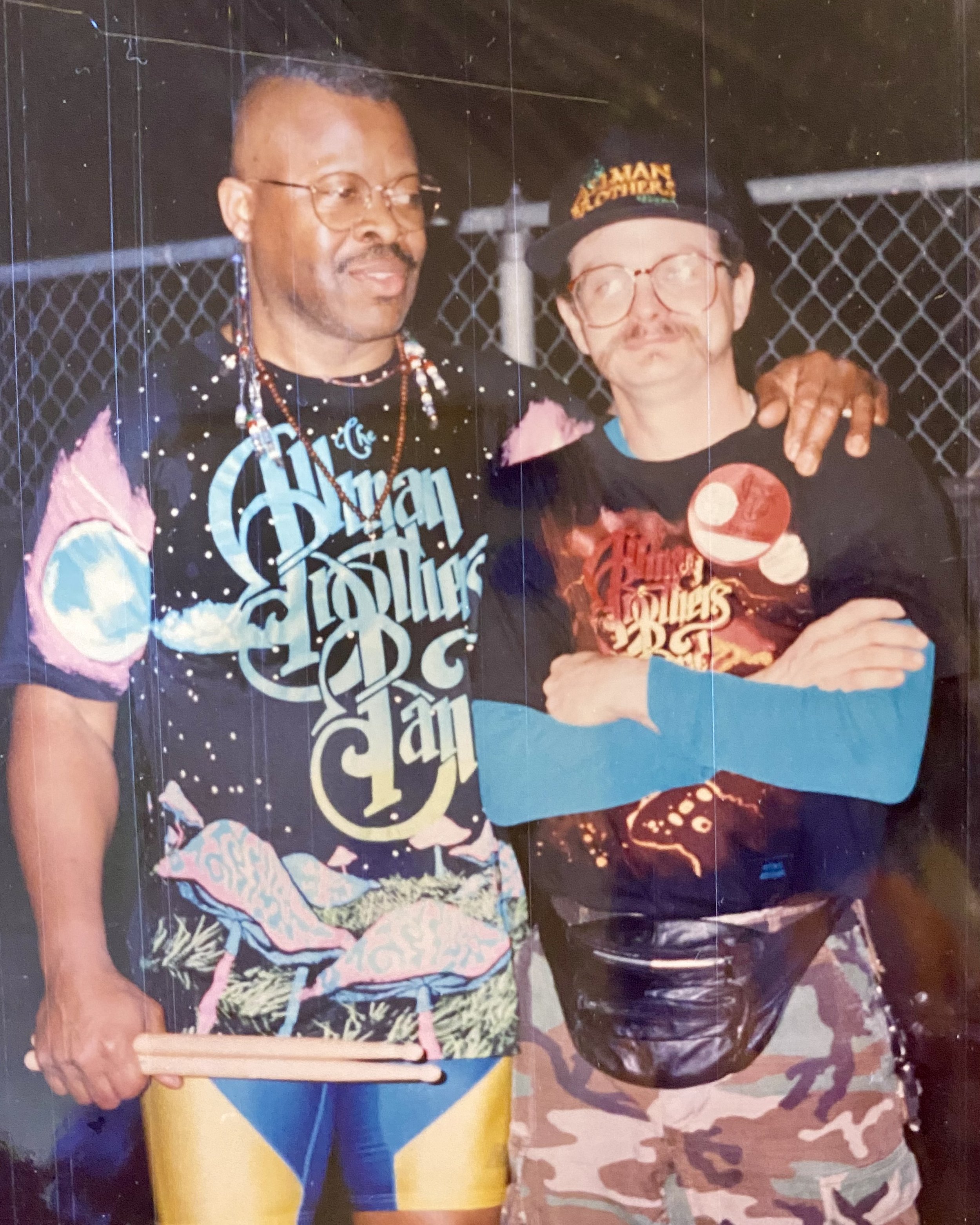

Kyler Mosely and Chris Hicks backstage at Center Stage in Atlanta—one of countless quiet moments behind the music. Photo by Kirk West.

They informally call themselves “the fellas from Lizella” — a loose brotherhood of cousins, neighbors, and old friends who came up on the same asphalt roads and kept finding their way back to each other through music.

When he gave me the grand tour of Lizella, it wasn’t just about the town’s layout; it was a history lesson sung in addresses. Along a main road, S. Lizella Road where he lives, he pointed out the spots where Mosely and Hicks houses once stood in clumps, and the ones still standing, where their aunts or grandparents had lived, all between the rivers and creeks that hem the place in like natural boundary lines.

Families in the South used to settle like that — spread out just enough to keep each other close.

His 90-year-old mother, Joyce (née Marshall) Mosely, hasn’t spent a single year outside Lizella’s reach. She’s lived in several houses within those borders, all within sight of someone she loves. The home she shares with Kyler today stands on the plot he grew up on. When the old house fell to termites, they rebuilt on the same ground. Kyler points to an aerial photo of their former home hanging above the mantle. Their house and porch may be new, but everything beneath them, and around them, feels like home.

Kyler Mosley with his mother, Joyce Mosley — mid-1990s and recent years.

Across the street lives Tim Pinson, bassist for Lizella Reign, the kind of cover band that keeps the local beat steady as ever. On Wednesdays, locals can hear their rehearsals drifting over the hedges — Southern and soft rock injected with just enough gospel swing. Their lead singer, Rhonda Porter, can raise goosebumps and rafters in the same breath.

Kyler invited me out one evening to watch Lizella Reign practice in a stand-alone building behind Tim’s house — air-conditioned, wired up, humming with amps and an organ that glowed like stained glass as Jerry Baker hit the keys. When the group plays the Pig & Fish over at Lake Tobesofkee, it’s standing-room-only and near impossible to get a table.

Most of the band members are old friends, men who’ve known each other since they were barefoot boys with borrowed guitars. They’re more Fellas from Lizella, these days retired — some from the Postal Service, some from day jobs that never quite replaced the thrill of a live set. A couple of them, Ken Wynn and Gary Porter, back up Macon’s beloved vocalist E.G. Kight, sliding between projects the way they always have: fluid and fearless.

Kyler knows them all, has probably recorded half of them, and supports every last one. To him, they’re friends, not just musicians — and stewards of a sound that blossomed under the Lizella pines and refuses to quit.

If Macon is where Southern Rock took flight, Lizella is where it built its nest — and Kyler Mosely, ever watchful, keeps it from going quiet.

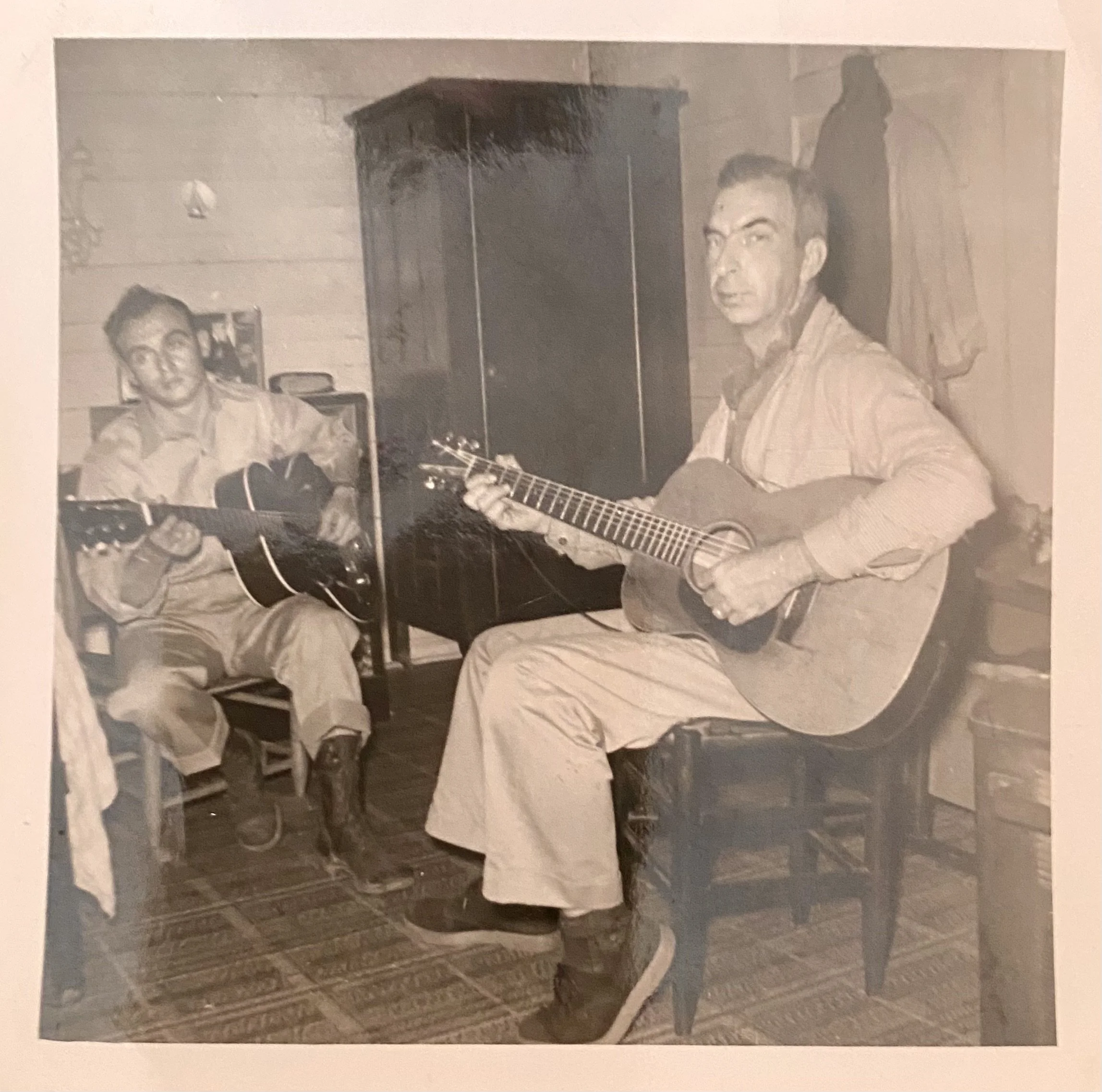

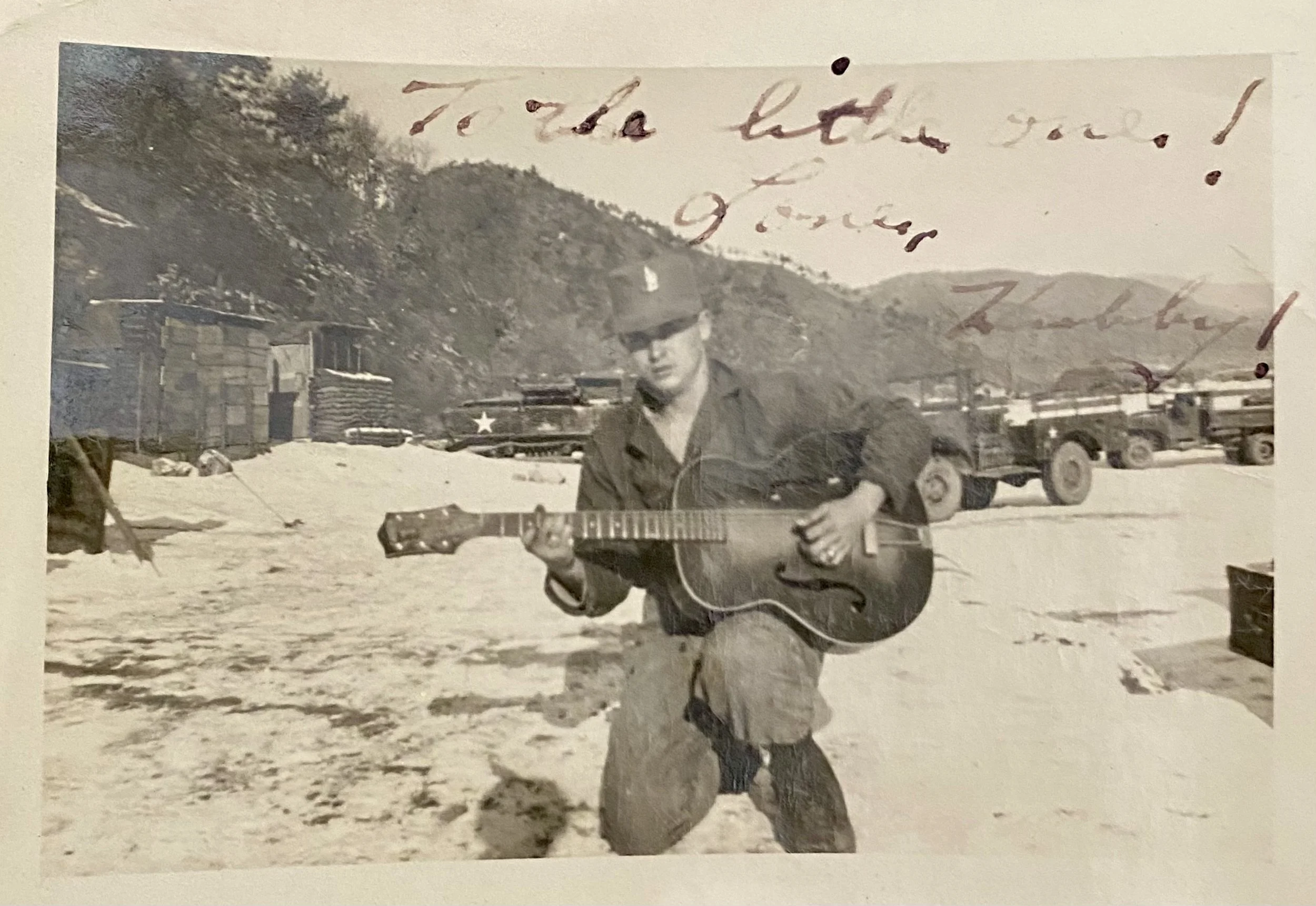

Lizella has been loud for a long time, though. Kyler’s own father, L. G. Mosely, played rhythm guitar and sang Hank Williams Sr. songs with a voice Kyler calls “pretty decent.”

Kyler Mosely’s father, L. G. Mosely, (back left) and Kyler’s Great-Uncle Buddy with their guitars at home and L.G. again with guitar during his service in Korea.

In the 1950s, before the ABB shook the Lizella pines, Uncle Ned’s Hayloft Jamboree lit up Macon’s WMAZ Channel 13 — a TV barn dance that Kyler was too young to see, but hears about from his neighbor and distant relative Roy Dean, 77, who remembers watching as a boy.

“When Uncle Ned died,” Kyler says, “his funeral was the largest one Macon had ever seen, until Otis Redding’s funeral.”

From Uncle Ned forward, Lizella has produced a significant run of working musicians: Eddie Cannon, Wade White, Tony Bullington, Vernon Wood, Mike Hyland (who recorded at Capricorn), and of course Chris Hicks. Chris and bassist Tim Pinson both took lessons from Mr. Cannon, who had the first eight-track recording setup in the Southeast in his house.

Kyler is quick to remind us the music’s roots were already deep before the Brothers ever plugged into Lizella.

The Garage Sessions

By junior high, Kyler had already figured out that if he couldn’t play, he could at least make sure the players had somewhere to plug in.

“I’d have jam sessions in my garage,” he says. The building sits behind the house like a small outpost — back then, it had no door, no electricity, just concrete and potential. They ran a drop cord from his bedroom out the back door, snaked it through the yard, and lit up a world.

Chris Hicks and Tim Pinson played there. Carey Jones of The Trebles, a white gospel group, was one of the first to set up in that little room. Tim Brooks’s band—performing under variations of his name before later becoming known as Tim Brooks and the Alien Sharecroppers— rehearsed there for five years with drummer Stanley Killingsworth. By the time guitarist John Vaughn was sixteen, he could walk out of that garage and see a yard full of a hundred people gathered from across town to listen.

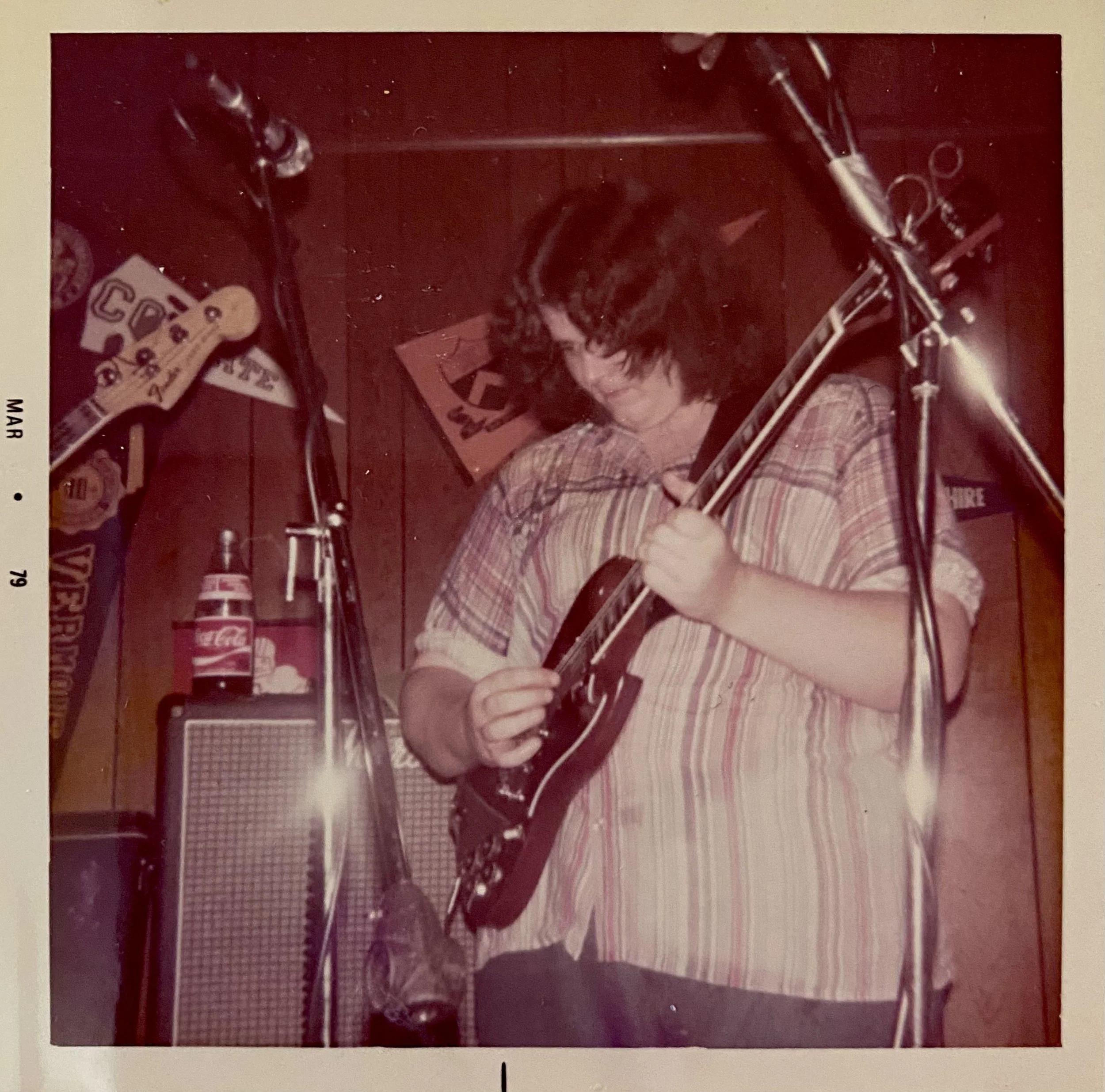

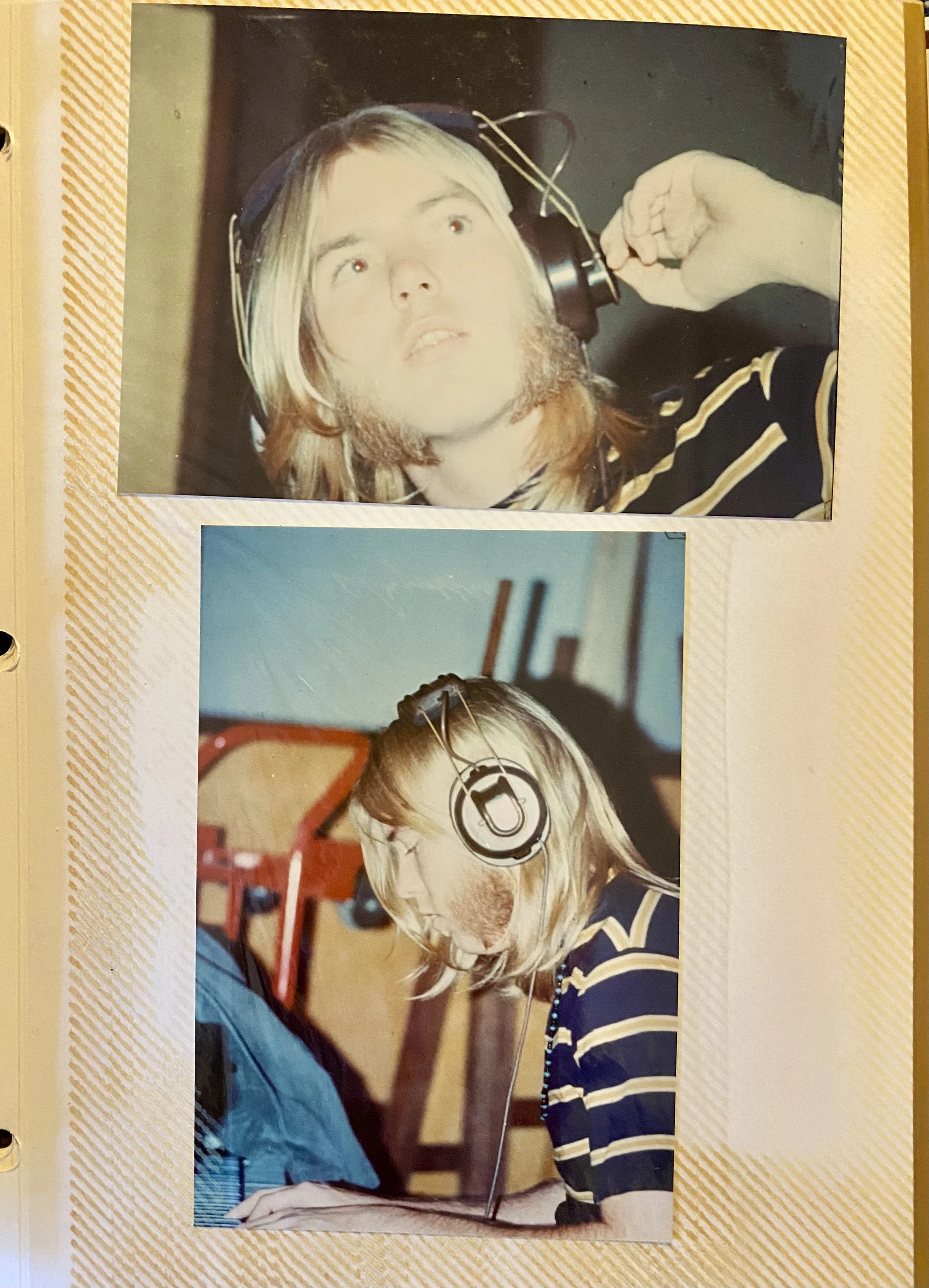

Tim Brooks on stage, 1979.

An early glimpse of a musician at the beginning of a long road—one that would intertwine with Kyler Mosely’s own musical life for a decade to come.

Tim and Greg Brooks were central to Kyler’s education — musically, emotionally, and culturally. They weren’t just players; they were a force. Tim had a reputation for a short fuse and supposedly that’s why Alan Walden passed on signing the band to Capricorn.

But Tim’s temper gets flattened into caricature unless you hear the truth from someone who was there. Kyler was there. He saw the fuse, yes — but he also saw the reasons it existed.

Macon’s bar circuit in the ’70s and ’80s could be brutal. Players were underpaid, overworked, and sometimes outright cheated by management. Everyone in town whispered how the Waldens could be slippery with money; even the Allman Brothers had to sue to recover a fraction of what they were owed. Lesser-known musicians fared even worse. Add to that the constant grind of drunk men testing themselves by picking fights with the biggest guy in the room — a kind of beer-muscle bravado that passed for Saturday-night masculinity — and Tim Brooks became an easy target.

“He had reasons to lose it,” Kyler says plainly about Tim. Somebody quitting the band right before a gig. Somebody touching his wife. Somebody trying to steal equipment. Somebody being too messed up to play. Somebody pushing him because he was physically imposing. The stories pile up the way they do around men who were both gifted and burdened, carrying more weight than people realized.

But there was plenty of joy, too, working the Brooks brothers — the good nights, the packed rooms, the long solos, the inside jokes, the unspoken loyalty of musicians who knew they were all each other had.

There was a moment at The Hangar in Macon when Tim Brooks stepped to the mic and introduced a brand-new instrumental, then looked right at Kyler down front. “Hey Kyler—come up with a title for this one.” Tim trusted Kyler to put titles to all of the band’s instrumentals.

Kyler listened hard and heard a little ZZ Top swagger in the bones of it. When the last note hit, Tim asked from the stage what he’d call it. Kyler hollered back, “Pulling Billy’s Beard,” referring to Billy Gibbons, lead vocalist and guitarist for ZZ Top.

Tim loved it.

Kyler made a little money in music, here and there, but he never made a living from it. He made his living as a plumber—fixing medical gas lines in hospitals across Georgia, plumbing apartment buildings in Atlanta, taking the jobs that paid the bills, and pouring everything else he had into the songs and the people he loved.

That work ethic took hold early. At sixteen, Kyler spent two summers picking yellow squash on his aunt and uncle’s farm, working long days in heat and humidity to earn gas money for the family car he was allowed to drive—and to buy records, of course. The labor was hard, repetitive, and unglamorous, but it gave him independence and a sense of what it meant to earn the things that mattered to him.

As an adult, even while working demanding jobs, he listened, remembered, wrote, recorded, steadied, and encouraged music.

And where stories might get twisted or lost, he has kept the truth of those years intact — because Kyler doesn’t do sugarcoating. He calls a thing what it is. If a story has splinters, he leaves them in. No smoothing the edges, no varnish. That’s why people trust his accounting of things.

Kyler recorded many of the garage sessions he hosted as a teen and young man, doing what he does to this day: making a way for the music to happen.

“Although I couldn’t play an instrument,” he says, “I found other ways to be in music — writing lyrics, making tapes and CDs and giving them away.” Over the decades, he estimates he’s handed out more than two thousand recordings. Not long ago he gave Stillwater’s founding member Al Scarborough a CD of an old session where Al was playing bass with Tim and Greg Brooks.

“Al hadn’t heard that song in years,” Kyler says. “Didn’t have a copy of it. He might not have even remembered recording it. Now he has it.” Kyler shrugs, like it’s a little thing. To the people who get those recordings back, it’s a huge thing.

For all his talk about not being a musician, Kyler’s fingerprints are everywhere in Macon’s sound. Over the years he wrote lyrics, turned riffs into songs, shaped arrangements, and handed tapes to players who trusted his ear. Some of those songs made their way into the hands of the pros.

“Quixote’s Theme,” for instance, became an Alien Sharecropper favorite — Greg singing lead while Tim, Rob Walker, Jimmy Gentry, Kemper Watson on bass, Mike Harrell on B-3, and Hubie Howell on drums carved out a full-band version that still circulates in certain circles like contraband gold.

When Tim Brooks cut Kyler’s tune “Peaches Are Sweeter,” the sessions included Albert Lee — yes, that Albert Lee, the Telecaster master who played with Emmylou Harris and Clapton — trading solos with Tim. Kyler tends to downplay his accomplishments, but these aren’t garage recordings. They’re the kind of sessions musicians brag about decades later.

He also nudged Tim Brooks into entering GUITAR PLAYER magazine’s instrumental contest with a piece titled “Made From Scratch.” Tim won. Kyler submitted the track, argued him into trying, and then stood back like it was the most natural thing in the world.

Their partnership produced dozens of ideas: titles, fragments, full songs, hooks, and grooves that Tim Brooks & The Alien Sharecroppers played live for years.

Some of that work survives on film. There’s rare footage of Tim Brooks & The Alien Sharecroppers on a European tour stop in Niederbipp, Switzerland, filmed March 17, 2001, one of the few moving records of just how powerful the band could be.

“This footage is some of the only real documentation of how awesome Tim Brooks could be,” Kyler says. “Even though I know he’d point out a dozen mistakes. Watching it brings up a lot — laughter and joy — but I don’t watch it very often. There are moments that still have me in tears.”

Kyler laughs, though, when he points out the “crazy version” of “Peaches Are Sweeter” tucked inside the set, at 1:23:00-1:31:00, and he’ll tell you where to find the essential moments if you’re short on time: 2:02:00 - 2:27:00. What he’s offering is an invitation into his memory and devotion, and the sound of something that mattered deeply and still does these ten years after the deaths of Tim and Greg Brooks.

Kyler may not have been in the spotlight, but the spotlight shone a little differently because of him.

The Bridge Between Eras

Spend an afternoon with him and you start to realize Kyler remembers history and lives it in real time, straddling two worlds. One foot in the yards of Lizella, the other planted firmly in Macon’s ever-evolving music scene.

He’s a bridge between eras — linking those wild ABB cabin jams to today’s backyard bands still hammering out chords beneath wood beams. With his work at GABBA, he keeps a hand on the pulse of preservation, helping to make sure the stories, photos, and people who built this legacy don’t fade into rumor. But he’s more than a historian. He’s a believer; he knows keeping a culture alive means feeding it, not freezing it in place.

For all his years celebrating other musicians, Kyler’s been keeping notebooks since his middle school years, scribbling down song titles and lyric ideas that come to him like messages from the beyond. Some of those pages go back decades, weathered and smudged from being carried to shows or tucked beside his tapes.

Music still visits him, sometimes when he least expects it. He told me about a song that came to him years ago on Eisenhower Parkway, chasing daylight to outrun a storm.

“It just dropped into my head,” he said. “I was riding my motorcycle like hell, trying to beat the rain.”

Tim Brooks & The Alien Sharecroppers later helped him record it, capturing that flash of inspiration in their easy, road-worn style.

Kyler has written other songs since then, though he’ll tell you there’s no one to play them.

“Everybody’s busy doing their own stuff,” he shrugs, a little wistful.

He played “Jessy” for me, a song he wrote in 1977 that was recorded somewhere in Macon years ago by Tim Brooks & The Alien Sharecroppers — a tight, soulful Southern rock song where every piece earns its place, and the crowd’s response tells you they felt it too.

“You nailed the Southern rock language in this one,” I say, standing in front of the speaker, listening hard.

“That was my intention,” Kyler answers, smiling.

“You should ask the Skydog band to play it at the festival,” I tell him. “The crowd would love it.”

Kyler just shakes his head. He doesn’t pick the playlists. They stick to the Duane canon. And he isn’t the kind of person who asks his friends to play one of his own songs.

Listening to “Jessy,” you can hear how deeply he understands the form — which makes it all the harder when he says he doesn’t really have anyone to play his songs anymore. That feels like a loss for all of us. The song slips so easily into the Southern rock bloodstream you’d never know it didn’t come from the Allman Brothers’ own family tree.

Every Middle Georgia picker, every drummer, every soul who has ever tried to turn a memory into a song is Kyler’s people. He carries their stories the way some folks carry family photos — carefully, always close at hand. And he will always put their music ahead of his own.

Kyler’s photo of The Beacon Theatre, New York City. He traveled north three times over the years to hear the Allman Brothers Band on their most iconic stage.

The Organizer

When Kyler starts planning a show, you can almost see him summon the ghost of Bill Graham, the fiery genius behind the Fillmore East and West. “Bill’s my hero,” Kyler says. “When I’m setting up GABBAfest, I try to think like him — keep it tight, keep it about the music.”

But if you ask him about GABBAfest or the Skydog festival, he’s quick to put the brakes on any talk that makes it sound like a one-man operation. Both are carried by a tribe, not a single pair of shoulders, he’ll tell you. While he currently serves as president of GABBA, he is quick to say the work has always been collective—shaped by board members, volunteers, musicians, venue partners, and a long line of people willing to give their time for the music they love.

Longtime members bring their own networks into the fold. Andy Johnson, ringleader of the ABB tribute band Restless Natives, taps his contacts and helps handle contracts. Jon Pierce from Perry steps in where needed. Former GABBA president Dave Pierson knows most of the scene by first name. Some meet future performers on the Legendary Rhythm & Blues Cruises. Terry Reeves, a veteran talent booker whose résumé includes Jimmy Hall and Wet Willie, is one of the quiet forces behind the lineups.

Over the years, leadership and stewardship have passed through many hands, including past GABBA presidents Greg Potter and Laraine Potter, longtime treasurer Surelle Pinkston, vice president Andy Johnson, along with countless committee members and volunteers whose names don’t always make the marquee. What endures is not one person’s imprint, but a shared ethic: show up, do the work, and keep the music centered.

“As President of GABBA,” Kyler says, “I’m more like one spoke in a wheel.” He helps keep that wheel turning, but he’s the first to tell you that without the other spokes, nothing rolls.

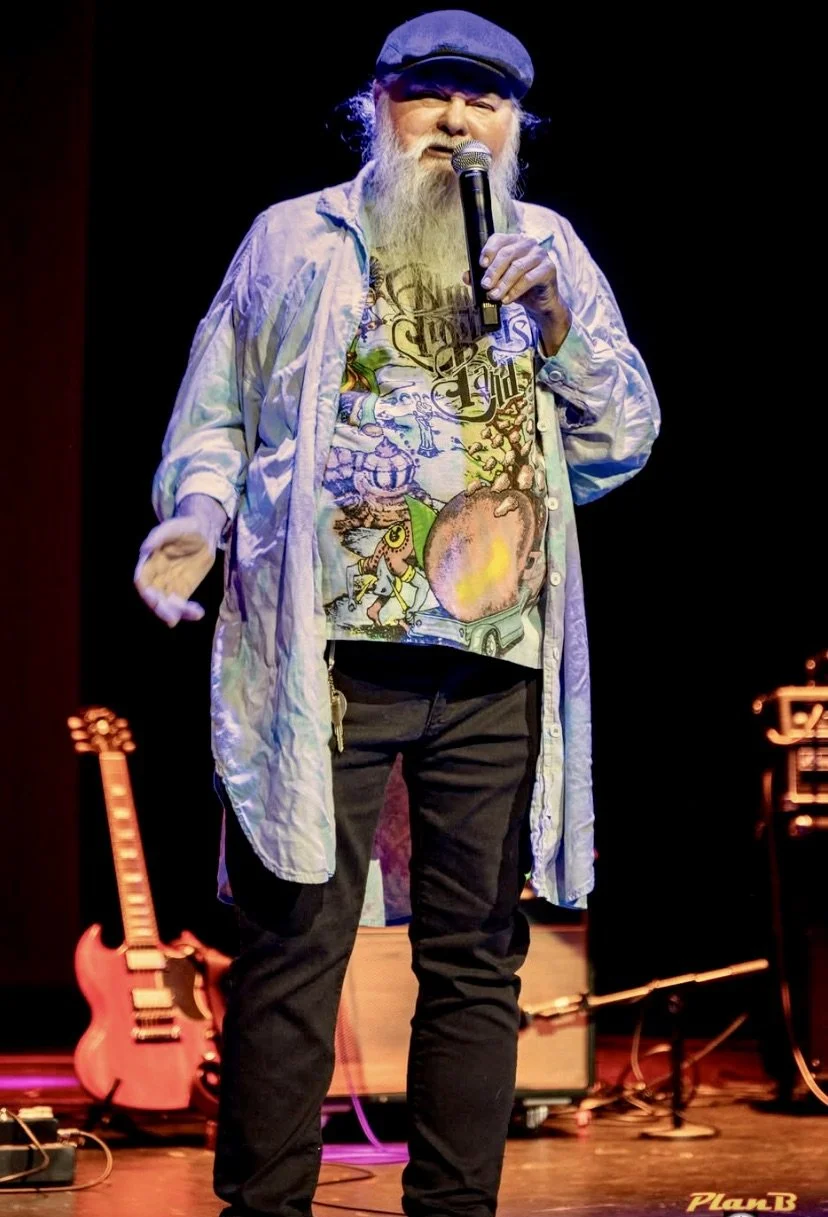

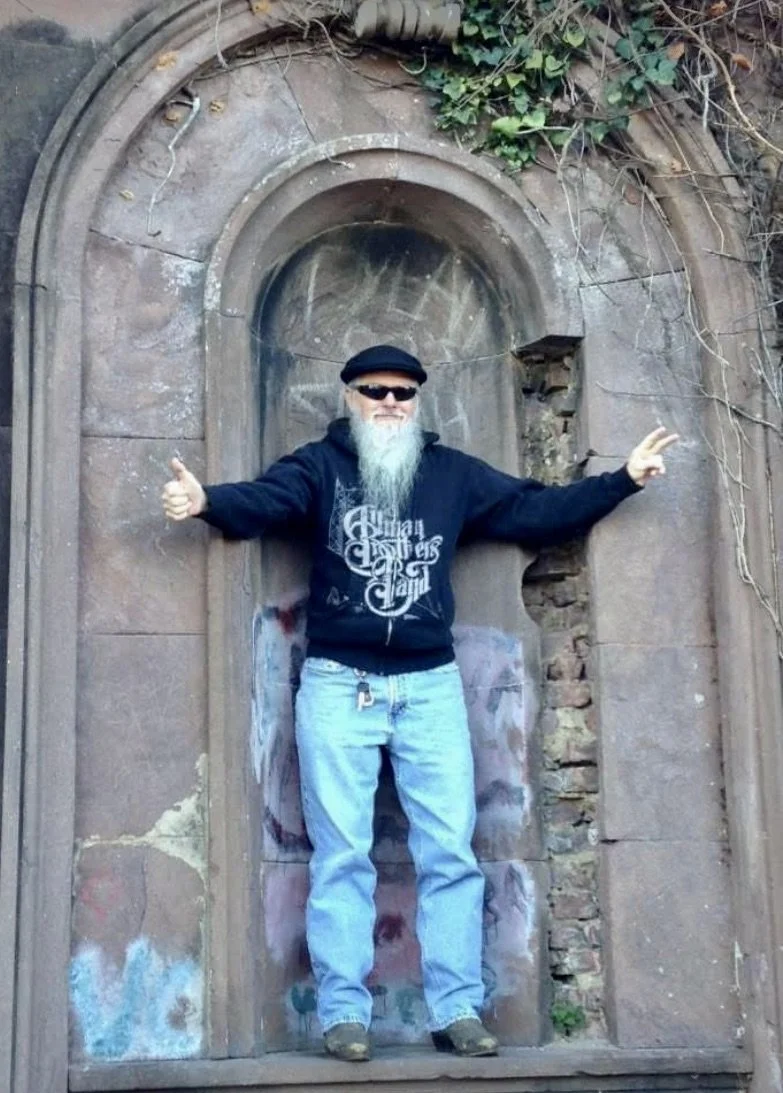

Kyler Mosely onstage at GABBAfest 2025, and standing beneath the Rose Hill Cemetery arch made famous by the ABB. A living connection between Macon’s musical present and past.

For more than thirty-five years, that wheel has carried a hard-earned legacy — one that still vibrates with the spirit of the ABB. GABBA remains fan club, preservation society, and spiritual revival knotted up together, and Kyler knows how to nudge all those parts in the same direction without making it about himself.

When I asked what keeps him going after all these years — through the festivals, the archives, the organizing, the endless details — he didn’t need to think about it. He just responded in a way that told us everything we need to know:

“Easy answer. I’ve loved the music the band made since 1969, and enjoyed the friendships — even the limited ones — with band and crew members since the 1970s, and especially with fans from all over the world that I’ve met because of The Allman Brothers Band. That’s fifty-six years’ worth, and I’m still looking forward to more.

As a songwriter and lyricist, the ABB has been inspiring and influential to me and to the musicians I’ve worked with to this day. They also led me to broaden my listening — to John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Taj Mahal, Paul Butterfield, Col. Bruce Hampton, Robert Randolph, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Herbie Mann, and so many others. I’ve dedicated a major part of my life to turning other people on to music I think they should be listening to.”

As noted, his listening doesn’t stop at Southern Rock. Kyler tells me about sitting on The Big House porch one day with Leroy Parnell—just two music minds swapping artists’ names—and Leroy turning him on to the Western swing history of Bob Wells and Milton Brown. Kyler enjoys widening his music map, following the trail backwards until he can hear where a sound first learned to walk.

His devotion to ABB’s sound, more than any title or role, defines Kyler. He has always preserved their story while spreading word about the sound that shaped him. After long days at the record store or on job sites, Kyler still went home to the turntable, the tape decks, and the endless work of keeping the music alive.

He can still picture how GABBA began: autumn 1991, a rented hotel conference room in Macon, and a fan from Chattanooga named Tom Holloway who invited anyone with ABB memorabilia to come share it. Kyler showed up, so did a handful of others, and before the weekend was over, strangers had turned into family. They also met on pilgrimages to Rose Hill Cemetery, cleaned the graves of Duane Allman and Berry Oakley, swapped bootlegs and stories, and decided they weren’t finished.

Nearly every year since that first gathering, Kyler has been at GABBAfest, the annual four-day celebration that brings musicians, fans, and historians from all around the world under multiple roofs and on The Big House Lawn. Ask him what he loves the most and he’ll say meeting fans from Europe, Australia, and other far-flung places.

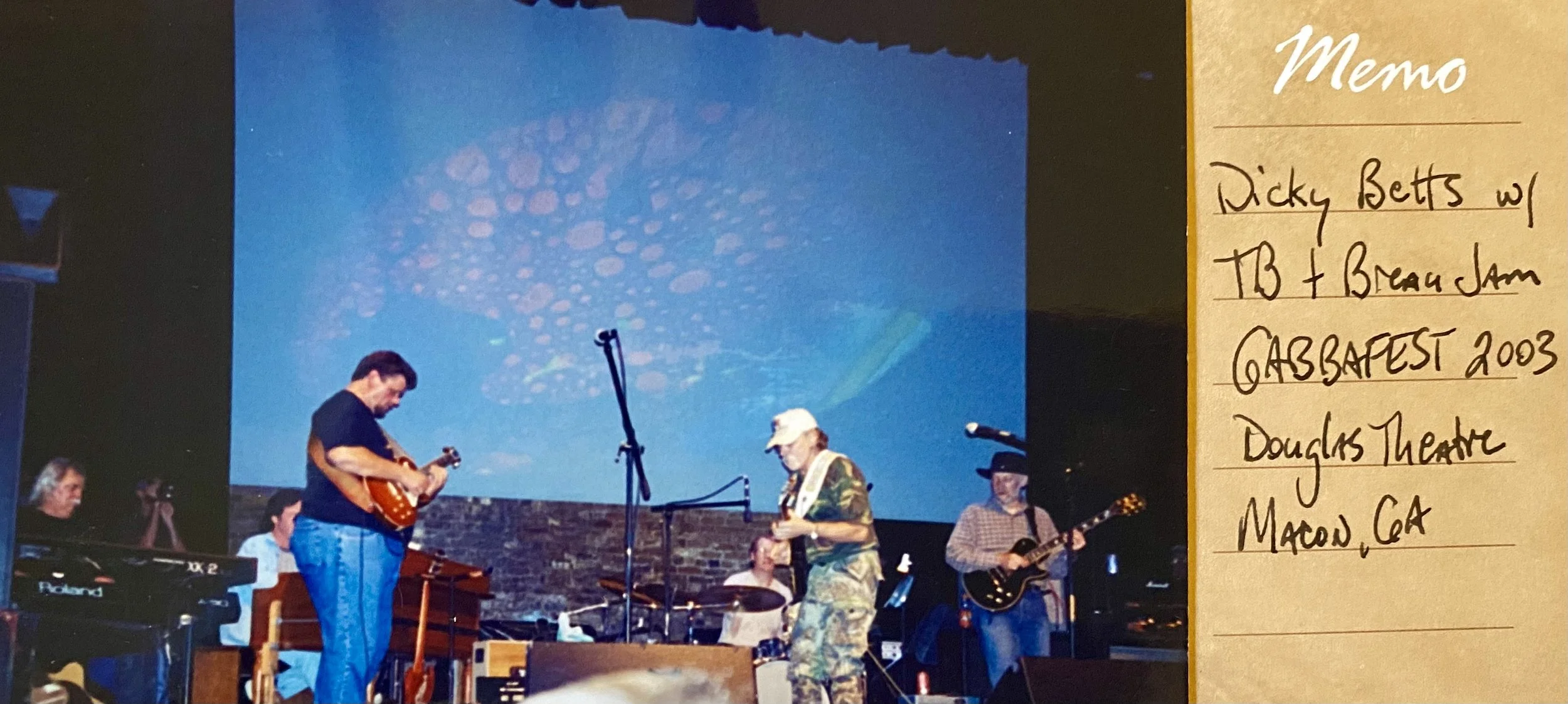

GABBAfest, 2003: Tim Brooks plays alongside Dickey Betts at the Douglass Theatre — a conversation between generations.

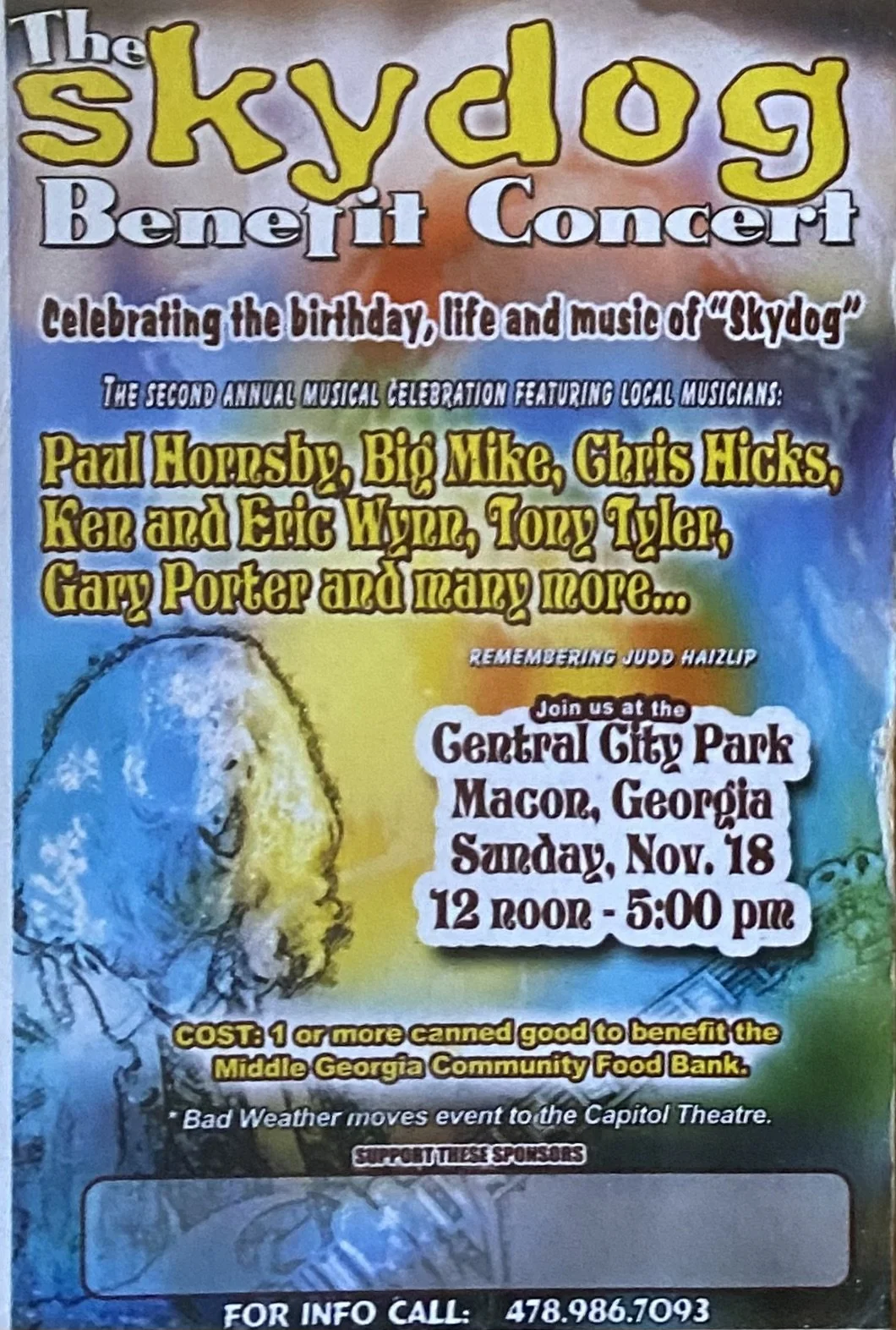

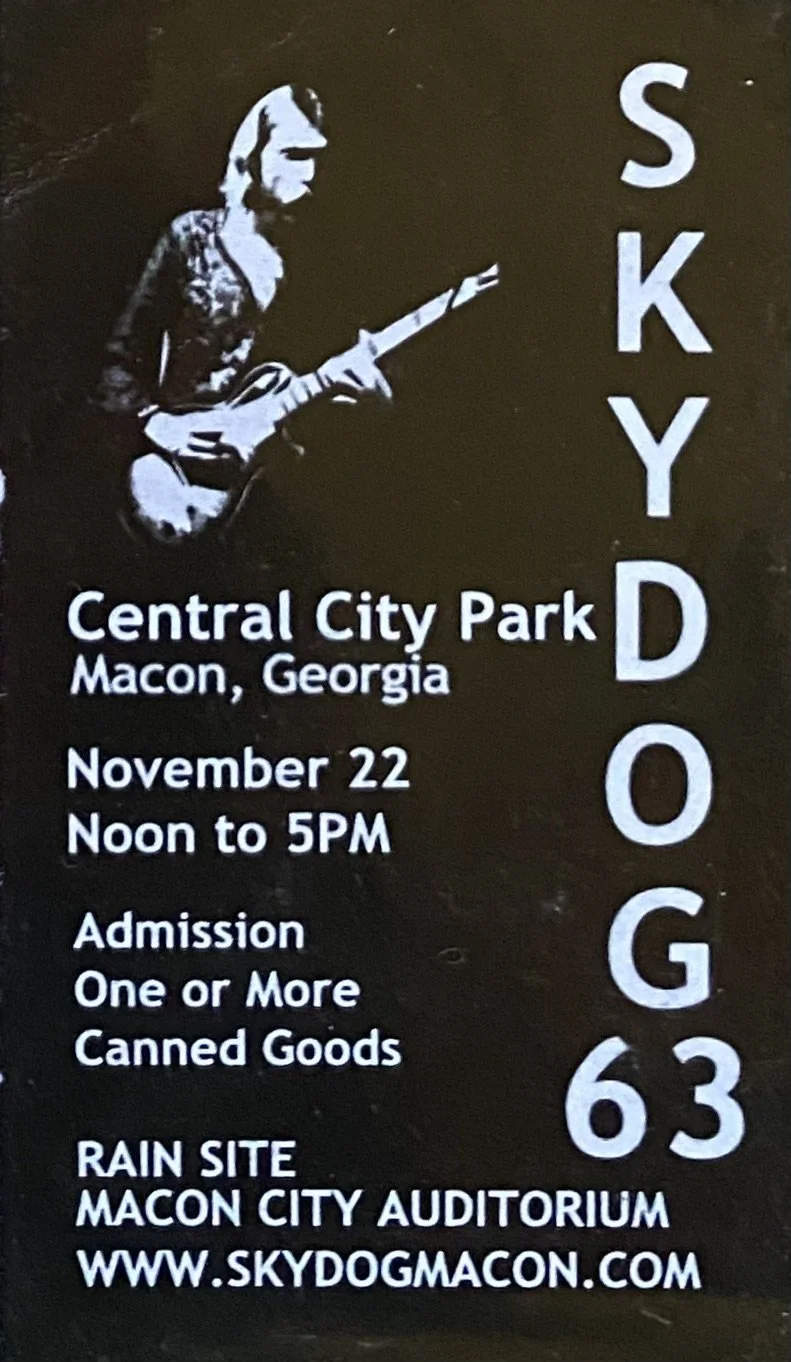

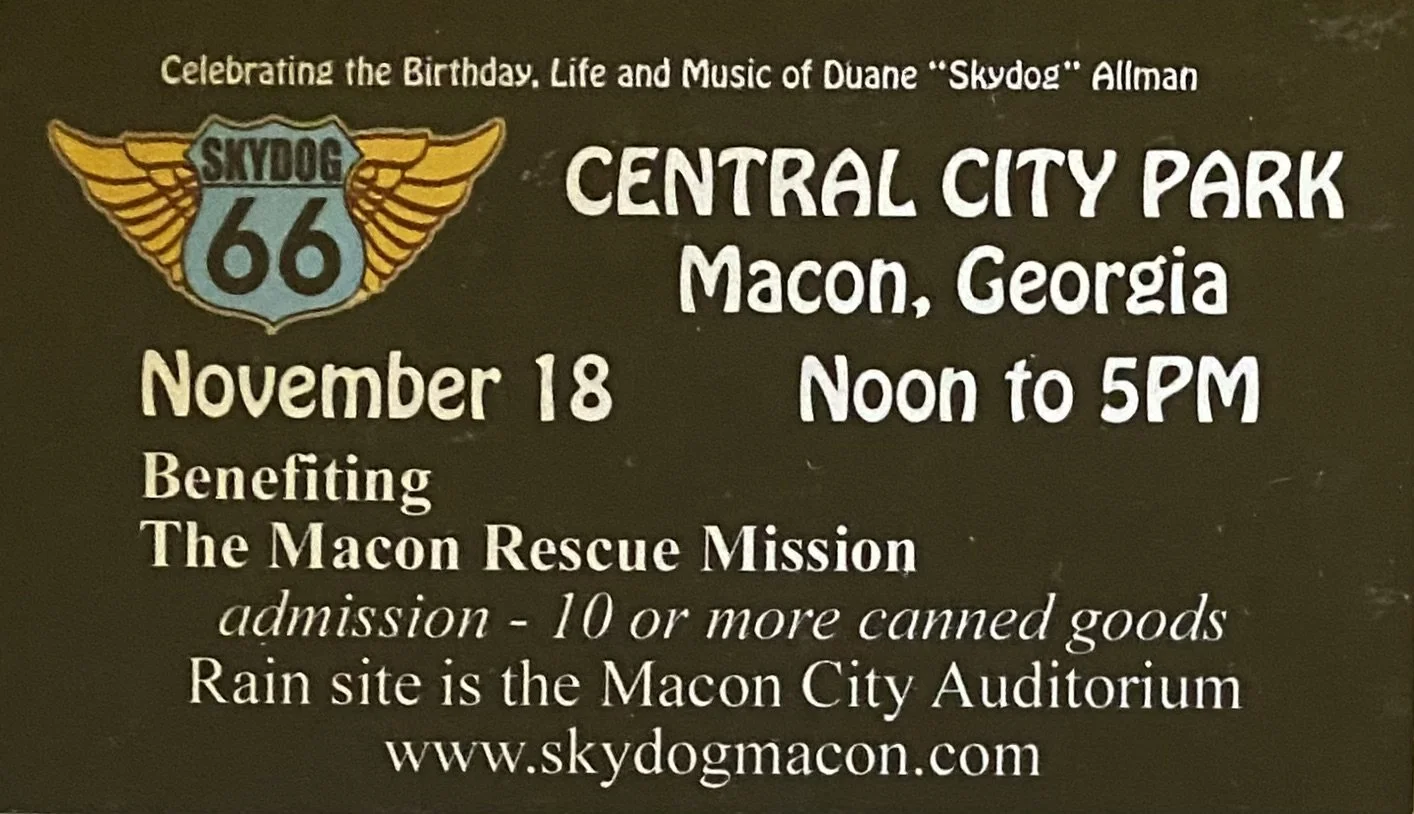

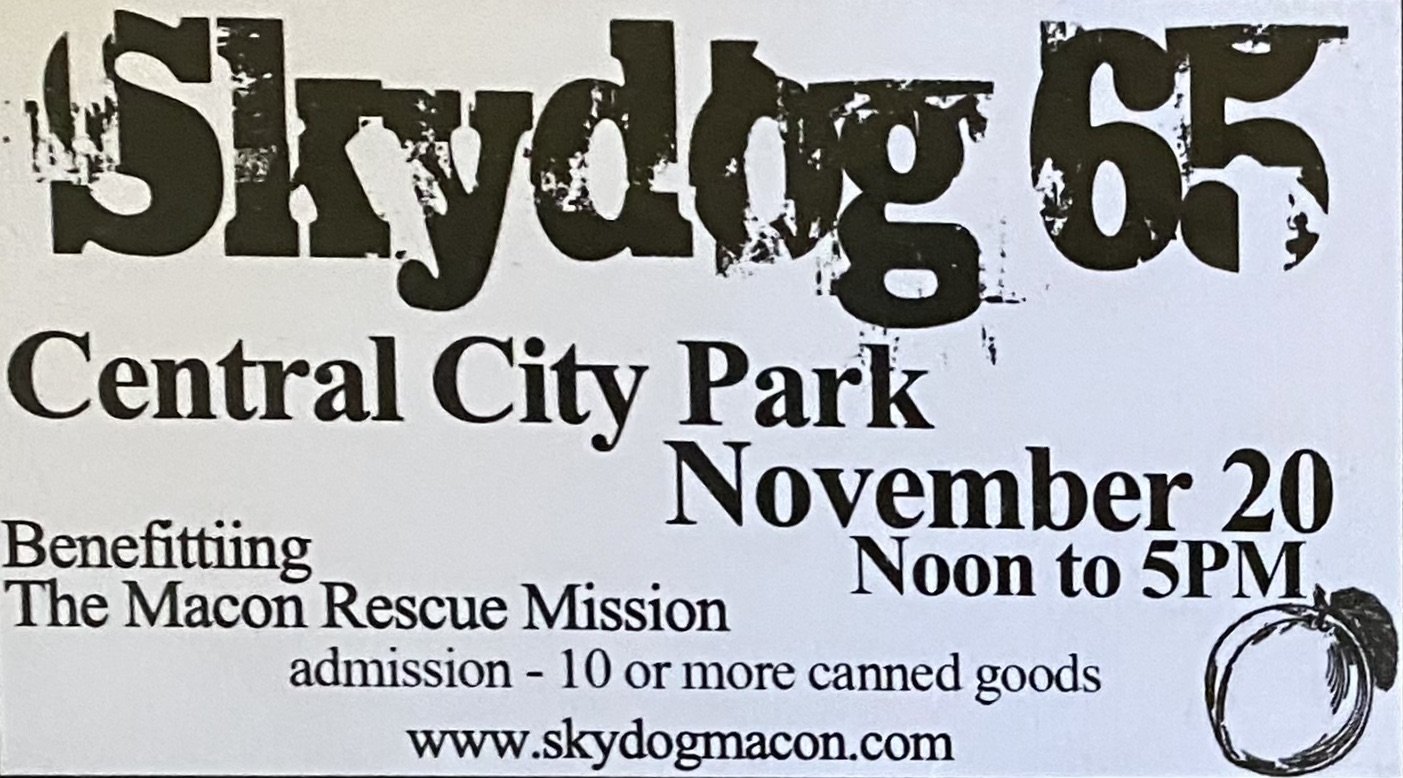

Kyler sees GABBA as the conscience of Southern Rock — the link between the original fire and the folks carrying torches now. He’s also one of the organizers of the annual Skydog Music Festival, working shoulder to shoulder with his Skydog partner, drummer and music-store owner Glenn Harrell, and a circle of volunteers who treat the day like a sacred trust.

And Skydog is sacred for several reasons; it honors Duane Allman’s legacy, benefits Daybreak Resource Center’s mission to support the homeless, and carries on the ABB’s philanthropic history. This year’s show brought together players and fans whose devotion hasn’t dimmed since Duane Allman died in a Macon motorcycle accident in 1971. Kyler calls it “a labor of love,” though it looks a lot like a full-time job.

What sets him apart is that he’s doing all this while managing diabetes, the aftermath of heart surgeries, and a kidney transplant just three years — proof that passion can outlast the body’s warnings. “I’ve had a lot of close calls,” he says softly, “but music always keeps me coming back.”

In 2011, Kyler came frighteningly close to the edge. Sepsis shut down his liver and kidneys and forced him into early retirement, followed by years of recovery that felt anything but guaranteed. More than once, he was told he’d survived by hours. When a kidney finally became available—just when he needed it most—he understood it as both medical intervention and mercy, made possible by the steady presence of family and friends who refused to let him face it alone.

Through it all, Kyler trusted God, trusted his doctors, and trusted that the outcome would be what it needed to be. And it was.

If Duane Allman built a sound that refused to die, Kyler and other die-hard fans are making sure it still has players and a home to play in.

The Collector

Step inside Kyler’s house in Lizella and you step into a living museum of American music. The air smells faintly of vinyl sleeves and history. Floor to ceiling, every inch holds a story — stacks of CDs, boxes of 45s and 78s, reel-to-reel tapes, music magazines, set lists, books, posters, turntables, and stereo receivers that still work like sacred relics.

He shrugs when people ask how big the collection is. “Fifty thousand pieces, give or take,” he says, though it’s clear the counting stopped mattering a long time ago. “The only room in the house without music,” he laughs, “is the bathroom.” He jokes, but it’s true.

It started when he was ten — a kid with a transistor radio and a fascination for every sound coming out of Atlanta’s AM stations… and later Z-93 and 96 Rock. He’d sit up late recording programs on cassettes. By his teens, he was hauling his Nakimichi recorder to live shows — determined to bottle lightning.

He recorded everyone: local bar bands, road-weary bluesmen, acts just good enough to make him believe. Some nights he’d come home with hours of music; other nights he got scolded for trying. One time in Atlanta, Tinsley Ellis saw Kyler setting up at a front table, getting ready to hit the “record” button. Tinsley stepped over and told Kyler not to record. Months later, Kyler ran into Tinsley, who immediately said, “Man, I wish I’d let you record that show. It was the best I’ve ever sounded.”

Kyler’s not smug about those moments; he’s protective. He isn’t bootlegging, he’s preserving. He has always offered the artists copies, keeping only the satisfaction of having caught something fleeting.

Before the collection became a mini-museum, it was also a day job. Kyler spent his working hours inside Macon’s record shops — from the mall’s Record Bar to the aisles of Steamboat Annie’s — absorbing the steady flow of new releases and local tastes.

For a brief stretch he even went on the road: the Great Southern T-Shirt Company hired him to handle merchandise on a Judas Priest tour. Three months in, budget cuts sent him home. But the point wasn’t glamour—it was proof that Kyler has always taken the long way around to stay near music: retail, road work, tape decks, composing, liner notes, and late-night listening.

His room of shelving is organized the way his mind is — meticulous, catalogued by intuition. There are handwritten notes on certain boxes, small memories tucked into CD cases, a kind of private Rosetta Stone for music devotees.

Standing in the room, it’s easy to imagine the sounds from all those recordings surrounding you — like a symphony swirling through time, around the eye of a hurricane, the listener anchored in calm. Those are the sounds Kyler has refused to lose. But collecting was never about possession for Kyler. It was about keeping company with the voices of his youth, the drummers who taught him rhythm, the singers who still feel like friends.

Kyler’s archive isn’t just audio. He has several deep stacks of music VHS tapes and DVDs, and he told me lately he’s been thinking about starting a monthly watch party—because performances are simply better with other devotees in the room. He described one tape that was shot at the Fillmore East months before the ABB recorded At Fillmore East—and how, decades later, he and his friends gathered to watch this rare tape, all yelling at the screen in unison when the cameraman panned away from Duane right in the middle of a tear-it-up moment. That’s Kyler’s kind of communion: laughing, groaning, fists shaking at the TV, arguing with history like it can still hear you.

“Now, if it’s a movie,” he tells me, “don’t bother me—I’m locked in.” But if it’s a movie concert, the more friends and the louder, the merrier.

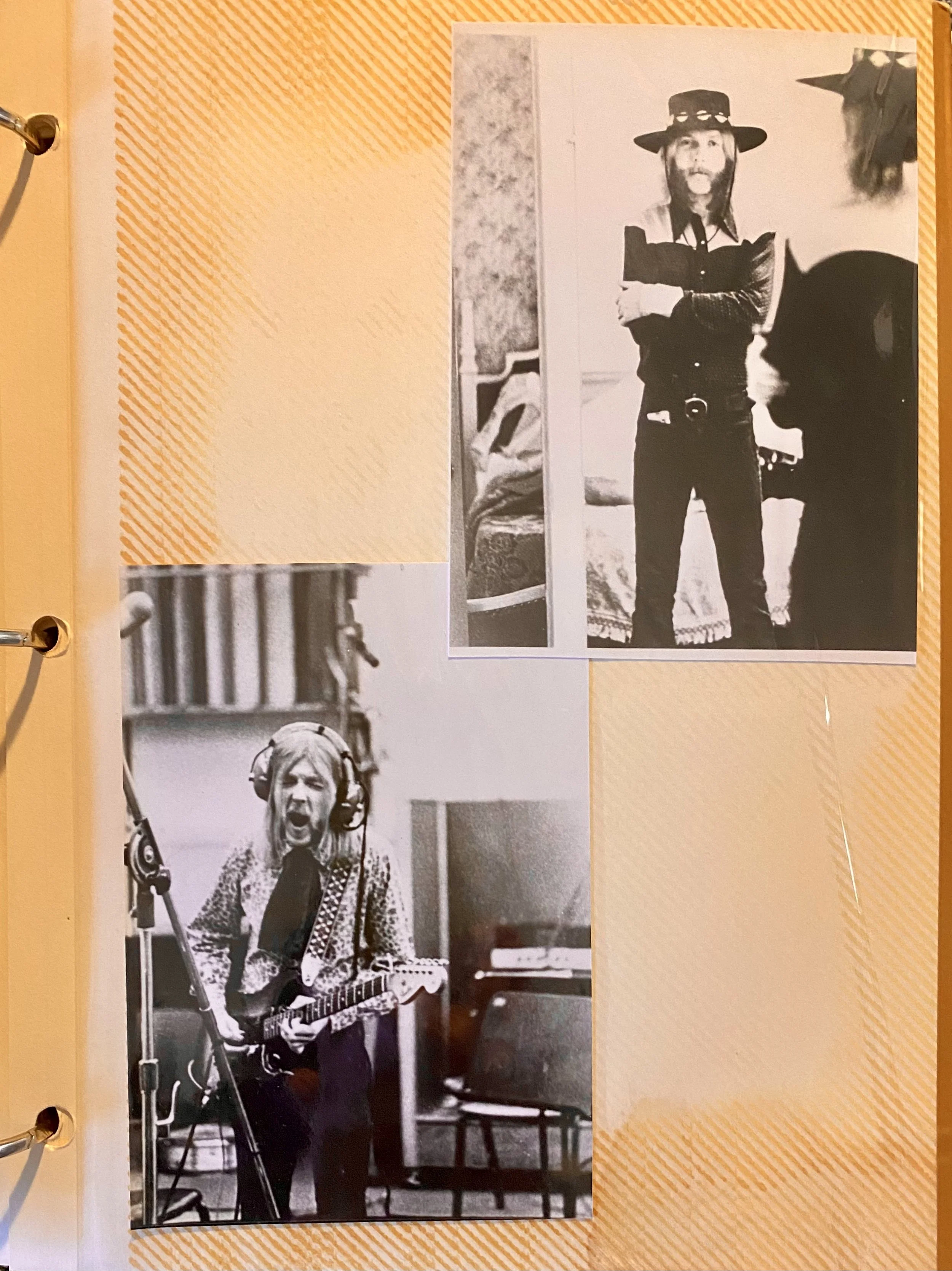

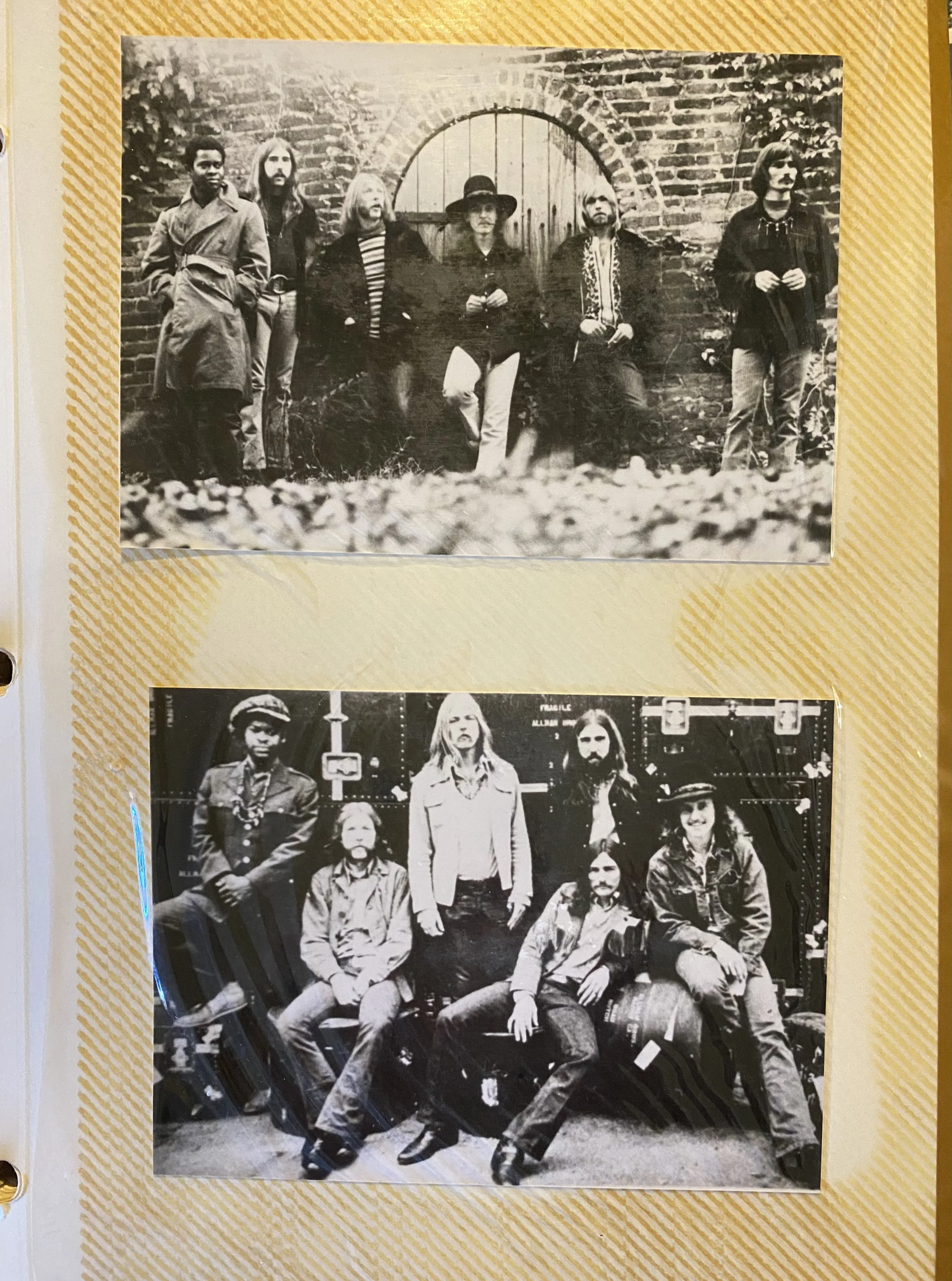

Collected images of the ABB from Kyler’s 1970s photo albums. Proof that the listening started early—and hasn’t stopped.

Learning to Listen — Jaimoe and the Art of Nuance

As a young man orbiting Macon’s scene, Kyler found himself in rooms with the older players — the lifers, the road-tested. Steve Kemp and Matt Greeley drifted in from Sea Level. Al Scarborough and Tim Brooks pulled him into long conversations about the Beatles, forcing Kyler to play catch-up on all things Beatles, and especially Side B of the White Album. (“Tim could play the whole thing on acoustic,” Kyler says. “It’d blow people’s minds.”) Warren Haynes turned him on to Robert Randolph and the Sacred Steel tradition.

Each of these men left a fingerprint on Kyler’s way of listening.

But the turning point came one night he was hanging with Jaimoe at The Rookery. Kyler had known Jaimoe since 1977, back when Juet Tucker brought him into the old Record Bar at Macon Mall, where Kyler was working. Jaimoe and Kyler became easy friends over time — long phone calls and longer philosophies — with Kyler sometimes plumbing Jaimoe’s house on Riverside Drive and sticking around afterward to talk music.

Jaimoe, who had lived a dozen musical lifetimes between the Allman Brothers Band, Sea Level, Tall Dog, and all the in-between ventures, didn’t teach with lectures. He taught from the side of his mouth — in those careful comments that land like stones skipping water.

That night at The Rookery, when an R&B band cycled through what Kyler thought was their usual twelve-song rotation, he leaned over and said, “Y’all always play the same songs.”

Jaimoe didn’t rise to it.

He just turned his head, gave Kyler that sideways look and said, “Well, if that’s what you think, then you’re not listening closely enough.”

That line struck Kyler like a tuning fork.

“That’s when I started focusing on the nuances of each instrument,” Kyler says. “And that’s about when I stopped recording. Because recording took away from paying attention. I’d be looking at the knobs, watching the levels. Just listening allowed me to focus — and enjoy the music more.”

It wasn’t listening for mistakes or high moments. It was about hearing what’s really going on, about what a musician intends — the emotional torque, the tension turning inside a solo, the choices made in the margins.

Kyler Mosely with Jaimoe and Warren Haynes, across different moments and years. Showing Kyler’s long habit of being there, again and again, wherever the music lived.

That insight changed how Kyler moved through music. It’s why, at the final rehearsal for Skydog this year, when Doug Peters was running Duane Allman’s “Elizabeth Reed” solo straight through at one emotional temperature, Kyler stepped in. He knew the piece like muscle memory — it’s his favorite song of all time — and he knew exactly where Duane always twisted the blade.

“He gets more intense mid-solo,” Kyler told Doug. “Almost angry. You’ve got to give it that.”

During the festival, Kyler stood right up front, watching, and halfway through the solo, just where Kyler had pointed, Doug turned around, cranked his amp, and dug in with ferocity. The sound rippled through the field, turning heads.

That is what Kyler brings to musicians. He gets people to show up, and then he listens deeply enough to help them find the heart of the song.

And it all began with that sideways look from Jaimoe, telling him there was more to hear than mere hearing.

The Rookery Years — R&B Under the Neon

While the Lizella woods were Kyler’s first classroom, hanging with Jaimoe and other musicians at The Rookery was his graduate school.

Starting around 1981, the neon-lit room on Cherry Street became a magnet for working R&B musicians. Band leader Bobby O’Dea held court there with a rotating cast of killers: Slim Powell on bass, Freddie Shang on sax, Robert Lee Coleman on guitar, Clarence Roddy on drums, and Jaimoe a regular presence. Many of them carried résumés that stretched from Sam & Dave to Percy Sledge, James Brown, Joe Tex, and Joe Simon.

Other sounds passed through — Triple Play, Widespread Panic, Caroline Aiken — but those R&B nights are the ones that live brightest in Kyler’s voice. “There were real players, real history up there on that tiny stage,” he says, still a little awed.

Those years hold his biggest regret, too. For a guy who’s documented so much of Macon’s music, the fact that he didn’t capture more photos and recordings of those Rookery R&B sets stings. “I wish I’d filmed and taped every one of those guys,” Kyler says.

Coming from Kyler, as usual it’s more about preservation — the fear that a vital chapter in Macon’s story might be remembered only in fragments, if at all.

Bobby O’Dea and Robert Lee Coleman also opened the door for younger players, including a young Chris Hicks, letting him sit in and learn on his feet. The music that poured out of that room entertained a downtown bar crowd and shaped the next wave.

The Musicians’ Co-op — Macon’s Own Piedmont Park

In 1986, Kyler helped midwife another experiment: a musicians’ co-op that turned Macon’s Central City Park (now Carolyn Crayton Park) into a Sunday laboratory. The idea was simple and radical — give local musicians and bands a place to play regularly, for the love of it, the way the ABB once did at Piedmont Park in Atlanta.

The Lifters, live at Central City Park, 1986. A working band in a shared space — borrowed gear, and pooled effort. No headliner. This was the musician co-op players building something together.

For three years, from 1986 to 1989, rock, blues, and soul rolled out across the grass. Players like Joe Dan Petty (one-time ABB roadie and Grinderswitch member), Big Mike Ventimiglia, Phil Palma, Ed Kane, Tim Brooks, Chris Hicks, Jerome Thomas (Capricorn session stalwart), Elbert Durham, Bill Pound of Boogie Chillun’ (those local white boys playing deep soul), and singer Mike Thompson all took turns jamming together.

Bands also joined those gatherings: Big Mike’s Vice Grips, Joe Dan Petty’s The Lifters, Kemper Watson’s Noble Jones, Tim Brooks & The Alien Sharecroppers, Just Blues, Keith Holloway, and more.

They used a stout PA system owned by Big Mike and Don Brown, borrowed from their nights at the Whiskey River nightclub. Kyler was behind the microphone, serving as host and M.C.

“These were musicians working together for a common cause,” he says. “To have fun.”

They gave themselves a venue and kept the music alive while sharpening their craft. And when the park gatherings wound down, many of those same players carried the co-op spirit into open-mic nights at The Rookery; the scene re-shaping itself, the way Macon’s music always seems to do, with Kyler right there in the mix.

The Eager Audience

Every band, player, and gig lives somewhere in Kyler’s mental hard drive — perfectly cross-referenced and instantly accessible. It’s like talking to an archivist, a journalist, and a best friend all rolled into one. He’ll be halfway through a sentence about the Stillwater band out of nearby Warner Robins and suddenly detour into a story about a drummer’s cousin who once filled in on trumpet at Grant’s Lounge in ’74. And he’ll be right — down to the night of the week.

“When I write down someone’s name,” Kyler says, “I’ll remember it forever.” Maybe that’s the secret. Maybe he’s been jotting down his love of music all his life in those notebooks. And he can summon those memories as easily as dropping a needle on a record.

When he was eighteen, Kyler met Donnie McCormick, the legendary drummer and founding member of the Eric Quincy Tate band. Donnie was one of those wild-eyed showmen whose rhythms felt like church revival mixed with bar-fight poetry. Kyler watched Donnie up close and never forgot it.

Kyler has met so many of his heroes that the stories blur into a living anthology, such as seeing Warren Haynes back when he was still playing with David Allan Coe. Or in the years before Derek Trucks was a household name, seeing Derek play at the Yellow Rose in Macon when he was barely a teen. Derek’s playing was so strong that Kyler’s date called home to say she’d miss her curfew; she wasn’t leaving until the music stopped. When the couple finally stepped outside, they were delighted to discover it had been snowing — another rare, magical thing.

For Kyler, those are’t just celebrity encounters; they are moments of connection in a long-running jam session called life.

He’s a truth-teller but he doesn’t gossip, although he could fill a book with what he knows: the break-ups, the bad decisions, the somebody-done-somebody-wrong episodes. He believes that keeping the record straight — who played what, where, and with whom — is most important and an act of respect.

Kyler talks about a jam out at Lizella or a half-forgotten set at the Grand Theatre with the same affection other people reserve for family reunions. In a way, they are his family — the endless network of Southern players who kept the sound alive through lean years and long nights… and still do.

He says he’s just documenting, but the truth is bigger. Like his friend Kirk West — who has spent a lifetime preserving the same world through photographs, archives, and the Big House itself — Kyler is a quiet custodian of a culture that might have slipped away without someone mashing the “Record” button.

The Broadcaster: The Whipping Post Radio Hour

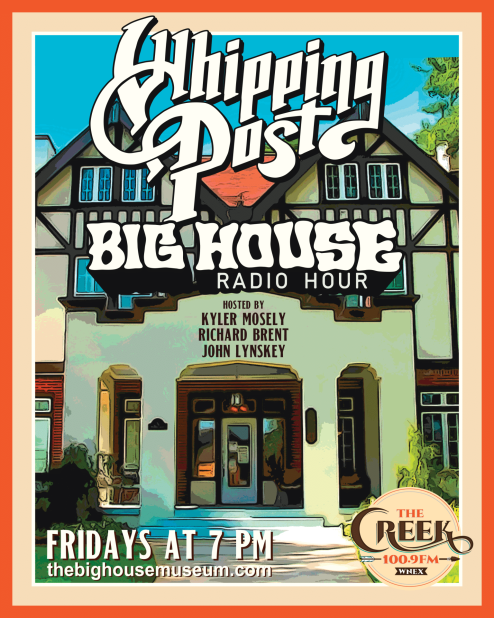

On Friday evenings in Macon, when you tune in to The Whipping Post Big House Radio Hour on 100.9 The Creek, and catch Kyler Mosely behind the mic, you’re in for a ride.

He co-hosts the show with ABB Historian and author John Lynskey, spinning the deep cuts and live takes that still make Southern Rock faithful feel like it’s 1973, and the road goes on forever. Richard Brent, Executive Director of The Big House Museum, joins in, adding his archivist’s precision to the mix. Together, they treat the airwaves like sacred ground — a weekly communion for anyone who ever wore out a copy of Eat a Peach or At Fillmore East.

Kyler has always been a communicator and story teller, once writing about music for the Macon Telegraph & News, now on-air. When Kyler speaks, you can hear both the fan and the journalist. And he’s not about ego. He’s about honoring the community. Macon is where soul lives, for sure, but Kyler wants to remind folks that it’s also where roots live — and roots don’t grow in straight lines.

The Whipping Post Big House Radio Hour already gives listeners a taste of that ABB lineage: the jam-band improvisations, the blues undercurrent, the church-born harmonies in sessions recorded in studio and/or live. Kyler’s platform is one where the next generation hears not just how the music sounded, but where it came from.

Kyler Mosely, Richard Brent, and John Lynskey, the voices behind The Whipping Post Big House Radio Hour, keeping the Allman Brothers Band sound alive on 100.9 The Creek.

In a way, he’s been preparing for this moment his whole life. From that kid in Lizella with a tape recorder, hearing that ABB sound drifting through the window, to the man surrounded by shelves of sound, he’s always been tuning the world toward one frequency: the truth of Southern music, played by the people who lived it and who live it still.

That commitment draws people to him — musicians, historians, fans, anyone who feels that tug toward the heart of Macon’s story. And it’s also what makes something else clear: Kyler isn’t just a broadcaster.

He’s a hub and a spoke.

He’s the person the scene revolves around, even when he’s sitting quietly at the back of the room.

The Connector

Ask around Macon long enough and a pattern emerges: sooner or later, every story about Southern Rock in Middle Georgia leads back to Kyler. You won’t catch him elbowing his way into the spotlight, but he’s always around — in rehearsal rooms, at side doors, in a radio booth, in pews at GABBAfest, listening with that quiet, intent gaze that says he’s filing every moment away. Musicians talk about him with gratitude.

Chris Hicks was still in high school when he started playing in Fresh Figs, the group that eventually morphed into Loose Change. Kyler was around for all of it. “I heard Chris Hicks when he was a youngster,” Kyler says, play guitar at Chris’ grandfather’s house. “I’m almost six years old than Chris.”

Kyler watched Chris and those early bands grow from local talent into something bigger, and he never stopped cheering them on.

Kyler also spent most of his teenage musical adventures with his best friend, Jimmy Hicks, who was Chris’ first cousin.

The Fellas from Lizella — MTB guitarist Chris Hicks, his cousin and Kyler’s lifelong friend Jimmy Hicks, and Kyler; three friends with lots of stories and no shortage of good trouble behind them.

So when Loose Change reunited last November at The Society Garden to honor the life of Dave Peck, it felt like a homecoming — for the players and for Kyler. From the stage, Chris dedicated his original song “Smile” to Kyler, a gesture that landed with the weight of decades. Chris, the musician and friend, was honoring the man who had been there since the beginning, bearing witness to every version of their parallel journeys.

After their show at Society Garden, Neil Rigole, an original Fresh Figs member, wrote on Facebook that Kyler is “a true gentleman, an Allman Brothers scholar and musicologist extraordinaire, and someone who knows the heartbeat of Macon music probably better than anyone alive.” That’s not PR, that sentiment is from Neil’s heart; it’s family talking — musicians recognizing Kyler, their life-long fan who’s been tracking every lineup change and venue through every era.

It’s like that everywhere Kyler goes. At GABBAfest, he’s the one connecting old friends with new ones and steering out-of-towners toward the right shows and hidden landmarks. At Skydog, he helps line up artists who can honor Duane’s spirit while also filling Daybreak’s shelves with essentials like shampoo and paper towels for people who need them most. Even a pre-Skydog rehearsal in a Gray, Georgia, music store turns into something deeper when Kyler walks in — a work night that suddenly feels like a tiny chapter in a much longer story.

What sets Kyler apart isn’t just what he knows; it’s what he does with his knowledge. He doesn’t hoard information, he shares it. He nudges bands toward each other, points fans toward acts they’ve never heard of, quietly corrects the historical record when stories start drifting, and opens doors for people who want to understand this world more fully.

If you’re a younger musician, he’s the guy who will hand you a bootleg or a name you need to know. If you’re a writer or a fan on the fringes, he’ll invite you to a rehearsal or a backyard jam so you can feel the music up close.

In recent years, that care has shown up in quieter ways too. When musician Tony Tyler, son of drummer Stanley Killingsworth, lost a close friend this summer, Kyler didn’t just “like” a social media post and move on; he wrote a message that wrapped Tony in memory and love, reminding him he wasn’t alone in his grief. He’s known Tony since he was a boy, and watched players like Dustin McCook and Adam Gorman grow from wide-eyed kids into the kind of guitarists who can hold a Skydog stage. If they end up on those festival lineups, it’s no accident. Kyler has been inviting them into the circle for years, making sure the next generation of roots knows how deep the tree goes.

That kind of watchfulness goes back a long way. Years ago, at an Allman Brothers Band show in Conyers, a very young Tony Tyler slipped out of Kyler’s sight — only to turn up moments later on the ABB bus. Gregg Allman looked up, took it all in, and deadpanned, “Oh shit, not another one,” sending the whole scene into laughter. Tony was fine. Kyler was mortified. And a story was born that still gets told with a grin.

Kyler’s eye for talent has been just as steady. He first met guitarist Dustin McCook when Dustin was nine and came by the house. Kyler put a guitar in the boy’s hands, listened for a minute, and thought, This kid is going to be something special. The first time Dustin came to Skydog, he was twelve. Red Dog, the legendary ABB roadie, walked him over to Kyler and said, “If y’all don’t let this kid play, I’m going to be pissed off.” Kyler and his Skydog partner Glenn looked at each other — and said yes.

Dustin has been part of the festival ever since. These days, as a member of Macon Music Revue, Kyler calls Dustin “the best guitar player to ever come out of Macon” — not as a slight to Duane, whose time was too short, but as recognition of a life spent refining the gift

The rest of that younger circle is just as loaded. Bassist Evan Benson — distantly kin to Kyler in a family tree Joyce could chart in her sleep — can move between guitar, bass, and keys with a fluency that makes older players grin. Watching them rise, Kyler sees the same spark he once watched in the garages and back rooms of his own youth.

Kyler knows you can’t understand the music from the outside; you gotta’ be in it, feeling it, to know it.

In an era when scenes can fracture into cliques and algorithms, Kyler keeps insisting on something older and sturdier: community. He doesn’t pretty-up what’s happening in Macon — he’s honest about who’s doing the work, who isn’t, where the legacy is being honored and where it’s being neglected. But even his bluntness comes from love. He wants the story told right, and he wants the music to have a future, not just a past.

In a town full of frontmen, Kyler Mosely is something rarer — the guy in the back paying attention and taking notes.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the weeks leading up to Skydog. When the festival nears, the circle tightens. Those musicians who have carried the ABB flame for decades rehearse a few times before the festival, beginning each evening the same way they have for years: breaking bread together at Old Clinton Barbecue in Gray, Georgia, then driving the short stretch to Wesley Music to make the room shake with the ABB sound. It’s tradition and reunion, entirely tied to the roots they all share.

SKYDOG Music Festival: The Brotherhood Gathers

Old Clinton Barbecue on Gray Highway is a time portal…the mismatched chairs, the ancient sideboards, the walls that haven’t changed since the Roosevelt administration, it all feels like stepping into Middle Georgia’s past.

At 5:30 sharp, Kyler is already there, tucked at a back table with a man talking plumbing. That man turns out to be Kemper Watson, one of the old-guard bassists who’s been hauling amps, running soundboards, and playing music since boyhood… in addition to being a full-time plumber and now owner of a sound equipment business. He still works hard at it all. It takes Kemper all of four seconds to shift from plumbing tales to a story about finding Paul “B” in Atlanta — a story that somehow ends with Kemper and Gary Porter playing alongside Mike Mills and Bill Berry long before R.E.M. existed.

This is how the community works: one story opens onto another, and every road leads back to these guys.

Within minutes, the wide table fills—Gary Porter, Sam-Elliott lookalike with a live-wire grin; Jerry Baker, wide-eyed beneath his ball cap; John Tinker, soon to be leaning over his Danny-Boyles-bespoke red guitar with monastic concentration; Dangerous Dave, vocalist; and others whose names echo across decades of Middle Georgia gigs, and lore. Their conversation darts from ’70s shows to YouTube clips to the fine points of which version of “Elizabeth Reed” they’ll follow at this year’s SKYDOG festival.

Every man remembers the first time ABB hit him in the chest.

“Midnight Rider,” Kemper says. “I was about eleven in my bedroom, around 11:30 one night when it came on the radio. I froze but somehow managed to stand up on my bed as if in a trance and just stared at the radio.” The look on his face still holds that childhood awe—the moment he realized something irreversible had happened inside him.

Kyler listens, nodding slowly, half-smile tucked under his beard. He has heard these stories a thousand times, and still he listens as if hearing them fresh.

This is why the group gathers: the ABB sound didn’t just inspire them; it claimed them.

It formed them.

The Skydog festival where these guys will perform is built the same way GABBA is: many hands, one heartbeat. Kyler may be the person you see at the mic, but he’s always quick to point to Glenn Harrell at the drum kit and mixing console, to friends like Kemper Watson, to the players and planners who turn a park by the Ocmulgee River into holy ground for a day.

Two miles up Gray Highway sits Wesley Music, a store on the outside but, inside, a shrine built from decades of accumulated devotion by owner Glenn Harrell, Kyler’s Skydog partner and a Macon native. The store is a maze of narrow paths and precarious stacks—guitars lining the hallway like saints, brass horns in drifts across the repair-room floor, keyboards layered three deep, filing cabinets braced against amplifiers, drum kits assembled from different decades and left where they landed.

You don’t walk through Wesley Music; you navigate it carefully, touching an amp for balance, sidestepping a snare, inhaling decades of dust and varnish. This is the sacred space where these assembled players rehearse for the festival.

Inside Wesley Music during a Skydog rehearsal — Gary Porter calling across the room, Kyler Mosely and Glenn Harrell conferring near the back, and bandmates threading their way through guitars, drums, and cables as the music comes together. In a space this tight, every note — and every person — has to make room for the others.

Kyler shifts between the front and the back of the room—arms folded in his familiar posture. His legs aren’t what they once were, but he stands all evening anyway because, as he says, “the view’s better.” Standing allows him to watch everything: who’s plugged in, who needs a cue, who is about to slip into the wrong arrangement. He can also dance a little. “If you can call it dancing,” Kyler chuckles.

Glenn Harrell, audio headset in place, amplifier turned up, acts as bandleader and foreman from the drum kit near the front door, giving directions to the musicians. Gary Porter settles behind the other kit like he’s sliding into a conversation; which is easy for him. Ethan Hamlin, from Macon Music Revue, takes his place behind the keyboard—focused, patient, ready — next to Jerry Baker at the organ.

Dr. Rob, the college professor, attacks the congas with revival fervor. Kemper Watson and Eric Wynn (playing in his socks) trade off on bass lines so fluid they feel inherited, which in a way they are.

Benny Mobley steps forward for one song and tears the roof off the room with harmonica. Ken Wynn proudly wears a t-shirt celebrating Benny’s win from the Big Bend Blues Society while Benny sits beside him all evening.

And Sonny Moorman all the way from Ohio slips in with electric guitar, later switching to his dobro and, together with Ken, delivering a version of “Pony Boy” that stops time.

When Glenn counts in and the music hits, sound compresses the air until the walls feel thinner.

Ken Wynn on guitar and his brother Eric Wynn on bass, rehearsing at Wesley Music, where barefoot players, battered cases, and narrow hallways leave just enough room for the music.

This is when the truth becomes unmistakable: the ABB recordings are beautiful, but the live sound is spiritual. It’d convert Ebenezer Scrooge. And in this overcrowded room—wedged between instruments, friends, spouses, veterans of a thousand shows—it’s easy to understand why people chase that feeling across states, decades, and lifetimes.

A brief cameo interrupts the rotation: Charles Davis, vocalist for Macon Music Revue and longtime on-air host at 100.9 The Creek. Having waited for his one song, he flicks a cigarette to the curb—“I know EXACTLY what I’m fixin’ to do with this”—and moves inside to sing “Whipping Post,” only the second time he’s sang the song in public.

Charles Davis of 100.9 The Creek and Macon Music Revue singing “Whipping Post” during a Skydog rehearsal at Wesley Music. It was only the second time he ever performed the song in front of others, caught on the fly from behind.

Kyler watches a brief post-song exchange between Charles and Ethan—Ethan gently offering a tempo suggestion, Charles acknowledging it—and Kyler absorbs the moment without inserting himself.

That’s his way: quiet stewardship. He tracks the setlist, the rotations, and the feel of the room. He steps in only when someone needs direction. He knows every ABB arrangement as well as the players do. And at this year’s 19th SKYDOG, Kyler will attend as he’s done every year since the earliest GABBA roots sprouted the festival. He’ll make sure the singers arrive, the guitarists switch in, and the rhythm section stays anchored.

He’s one of the steady centers of this extensive community, a cool core of energy around which friends, players, and fellow organizers naturally gather.

Rhonda Porter steps to the mic and sings “The Weight,” then lends backing vocals to Dangerous Dave as he wails on “Midnight Rider” and “Revival,” her voice grounding the songs with warmth and easy confidence.

As the rehearsal winds down, the standout moment arrives: two dobros—Sonny Moorman’s and Ken Wynn’s—folding into “Pony Boy” with a bright bluegrass bounce that lifts the entire room. Everyone stops to listen. The glow on faces is unmistakable and folks linger long after the last note fades. Joy hangs in the air like dust in stage lights.

Ethan mentions the young man who once attended Skydog as a tourist and moved to Macon the very next week because of what he had felt there. Another fan flew from South Carolina for this year’s festival after meeting John Tinker on a river cruise in Europe and hearing about the Skydog vibes.

The call of this brotherhood travels far.

This thing that’s happening in Macon, Georgia, is unique in all the world.

Nowhere else has the sound of a band and the genre it created been kept alive for generations, in place, driven by dedicated musicians and fans.

At the heart of it—quiet, steady, observant—is Kyler Mosely, keeping the circle unbroken and ensuring that the love of this music—its heat and history—moves cleanly into the hands of the next generation.

Inside a Skydog rehearsal at Wesley Music — The last two minutes of “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” caught as it happened, the band finding its way back into the groove. (Doug Peters on lead, Ben Wynn on guitar, John Tinker on rhythm, Gary Porter and Glenn Harrell on drums, Ethan Hamlin on organ, Rob Syzmanski on bongas, and Kemper Watson on bass.)

SKYDOG 79: The Rehearsal That Became a Revival

What started in that packed rehearsal room in Gray bloomed into something unstoppable on Sunday afternoon, November 23, 2025, down by the river. Skydog 79 arrived dressed in a blue sky and a breeze. Past years had people bundled in parkas; this year had folks in T-shirts and folding chairs, fanning themselves… and some pinching themselves at the perfect weather.

They came early, claiming the shade of the trees first and then filling the open field until the place looked four times the size of past festivals. And from the first downbeat of the Younger Brothers, you could feel it — something moving through the crowd… recognition and continuance by the generation Kyler has been championing; Ethan Hamlin, Dustin McCook, Caleb Melvin, Dalton Love, and the others came out swinging, and Ethan — playing all day with the Younger Brothers, Macon Music Revue, and the older guard — looked more and more like a young musical director beginning to shoulder a legacy.

Kyler, in his yellow Skydog shirt, kept the day flowing. He spoke to the crowd the way he does during GABBAfest and in rehearsals—easy, direct, warm—guiding the sets, honoring the ones we’ve lost, and keeping the whole ship pointed toward the music. When Charles Davis from the Macon Music Revue band and 100.9 The Creek radio station opened his mouth on stage, the entire crowd snapped to attention; by the second song, people were looking around like, Did we just witness that? You could feel the collective intake — the recognition of a voice that’s not just good, but touched.

And then came our boys from the brotherhood, and the guys and gal from Lizella Reign — Kyler had stood with them in rehearsal hearing the parts lock in and now he watched them erupt onstage.

The man standing next to me staggered a little from disorientation, not drink, and leaned in, eyes wide: “Two drummers! Have I died and gone to heaven? That’s not music… that’s a religion.” You could see it working on him, the revelation so many people have when they hear this music live, the way it rearranges something inside. A reaction Kyler has witnessed countless times — the ABB’s live spirit grabbing someone by the collar for the first time.

Another man, older, told me he’d seen the original ABB in Charlotte. “Hearing this brings me right back there,” he said, “feeling just as I did as a young man,” and then his blue eyes teared up.

That’s what happened out there. These players weren’t reenacting the ABB, they were resurrecting them.

“That fella’ there,” a third man said to me, pointing at Doug Peters, “he’s the smoothest player up there.” Doug was killing Duane’s slide solos, as usual, with no facial expression.

Benny Mobley played harmonica like it might keep him out of jail. Dangerous Dave sang with everything he had. So did Rhonda Porter. And her husband Gary was beating those drums like Butch. A rotation of young guitarists came through the set, including Ramsey Wayne, who had been at rehearsal.

These were the musicians Kyler trusted, the ones he knew could carry the weight of the day. And they did. If you weren’t looking at the stage, you’d swear the ABB was up there.

The sound system was flawless. Kyler had worked with Glenn Harrell and Kemper Watson’s team to ensure the sound would be worthy of the music. Kemper’s crew mixed it so clearly you could hear every slide squeal, every snare ghost-note, every organ swell.

Sonny Moorman and Ken Wynn took their dobros through “Pony Boy” while Willie Perkins — who once shared a house and many hotel rooms with Duane Allman — sat at the back of the stage, his client onstage honoring a man he himself had loved and lost. It was one of those quiet full-circle moments that can only happen in Macon.

And the crowd wasn’t just gray-haired faithful. A pack of mid-twenty-something men stood near the stage, dancing, recording, groovin’ like they’d found a doorway into another world. You could see it catch hold of them — that live electric shock of Southern Rock played by people who know where it came from. This was exactly what Kyler hoped for — younger listeners catching the fire.

By late afternoon, the festival had raised $27,000 for Daybreak, plus a truckload of supplies. In the early days the ABB played benefits around Macon to lift up the community that lifted them. That spirit is still here — unbroken.

Before the day was over, Kyler was announcing next year’s 20th annual festival — two days instead of one, for the first time ever. A milestone, and a promise. It’ll be called Skydog 80; Duane’s age if he had lived.

This, along with GABBAfest, is the world Kyler stands in the middle of: the only place on earth where this music is not just remembered but is protected and passed forward.

This brotherhood of musicians, who have played this music since their teen years, and who have played together in various versions of various bands, still work like hell to nail every note just as the Brothers had done it.

They’re in the same club of folks keeping Macon’s sound in the forefront, folks like Kirk and Kirsten West who bought the Big House, and Willie Perkins, former ABB road manager, and national acts, like Devon Allman and Duane Betts’ Allman Betts Family Revival, Derek Trucks and Susan Tedeschi’s band, Warren Haynes and Gov’t Mule, all carrying that sound across the country.

This network is a living fellowship of musicians, crew, and fans who bring forward the spirit and improvisational language formed in Macon, the ABB’s adopted home. It is ABB-centered but not ABB-limited. This community moves easily across the full Southern rock spectrum because the ABB’s musical vocabulary is wide enough, deep enough, and soulful enough to contain all of it.

As already noted, this musician-driven passing-along of a sound, in the place it incubated, doesn’t happen anywhere else in the world. Only Macon. And only because of the folks who have devoted their lives to preserving the sound. Folks like Kyler Mosely.

The Man Behind the Music

Spend enough time around Kyler and you start to realize that his generosity in the music world traces back to something older — the family that raised him and the land that shaped him. He was absorbing rhythms long before he recorded his first show.

Kyler’s mother Joyce once clogged all over the state, in competitions and parades and community halls. Even now, she’s a proud member of the local clogging chapter, though she no longer dances. Perhaps her rhythm is what first tuned Kyler’s ear.

His father, L. G. Mosely, a Korean War veteran, came home carrying wounds no one in those days knew how to treat. Combat left him with what we now recognize as PTSD, and alcohol only deepened the storm. But the roots of that pain reached back even earlier. L.G.’s parents divorced, and both remarried, leaving him moving between households where he never quite felt settled or safe. Kyler says his father was unhappy in both homes — belonging nowhere, misunderstood.

There was, however, one place of real refuge. As a boy, L.G. spent time with his grandmother in Valdosta, who helped raise him. In Kyler’s telling, her home was the happiest, safest place his father ever knew — a rare pocket of calm in a childhood otherwise shaped by instability and unease.

By the time Kyler was growing up, that unhealed past lived inside their home. The house could feel unsafe when his father’s temper rose — first in flashes, then more often, until tension became part of the air itself. When that happened, Kyler would retreat to his room and put on music, or read. He’d turn up the volume until it drowned out everything else. Music and books weren’t just something he loved — they protected him.

At school, he became the good kid, the teacher’s pet. Not out of ambition, but because he was searching for steadiness and kindness — places where rules were clear and voices stayed calm. He learned early how to read a room, how to stay out of harm’s way, how to keep the peace.

“Music and reading were my refuge when I was growing up in a verbally abusive home,” Kyler says. “They were a serious part of who I am and how I got through it.”

There were frightening stretches. His father’s struggles eventually required hospitalization, at a time when mental health care relied on blunt tools and unquestioned authority. Kyler remembers visiting him then as a teenager — wanting desperately to help, but powerless in the face of decisions made by doctors and adults he was taught to trust. When his father came home, something in him felt altered, dimmed.

Despite everything, Kyler speaks of his father with complicated love — of the good days, when he was gentle and proud, and of the pain that shadowed their home. In those years, men — especially veterans — were rarely encouraged to ask for help. Suffering stayed hidden. Drinking blurred judgment. And damage passed quietly from one generation to the next.

Kyler stopped it, though. He did not carry his father’s violence forward. He learned what restraint looked like. What gentleness required. The chaos he grew up inside did not become the man he became — though it shaped him, taught him empathy, and left marks he still tries to understand.

When Kyler was just twenty-one, his father took his own life. That devastating loss closed one chapter and sharpened another. Music, once a refuge, became something larger: a way to connect, to protect others, to build the kind of community he had needed as a boy.

Kyler found first refuge, then purpose, in the music he escaped into. It laid down the rails of his life, running past backroad stages, over dark rivers, through pine forests and into those rooms where songs got made — and some songs were his own.

Through it all, Joyce was the anchor — working at the First National Bank in downtown Macon for more than forty years, raising her sons with steady love and humor. She never wavered in her support of Kyler’s devotion to music, even as the stacks of records slowly took over the house and bands practiced regularly in their garage.

Just a portion of Kyler Mosely’s personal archive, containing thousands of albums, CDs, tapes, and music books — all within arm’s reach and part of the living collection he draws from for radio, festivals, and preservation work. Also included are small artifacts that tell the real story of a life spent inside music.

Surely there’s a photograph somewhere of Kyler as a boy, ears full of sound, eyes lit like he’s just discovered fire. In a way, he did. The music that drifted through the trees and out of the speakers became a map for everything that followed — the recordings, the radio shows, the GABBA meetings, Skydog, the friendships.

Now, when he sits in that room full of vinyl and tapes, he’s surrounded not just by music and books, but by proof of endurance. Every record kept and book read is a small victory over time.

Legacy of a Keeper

There’s a certain light that settles over Lizella in late afternoon — soft, honeyed, forgiving. Inside the Mosely home, it slides across the spines of vinyl albums and stacks of CDs like time slowing down to listen. Somewhere in the next room Miss Joyce navigates her phone’s screen, and Kyler sits surrounded by his life’s work: fifty thousand echoes of the South and beyond.

He’ll tell you he’s just a fan, but that’s selling himself short. Kyler is one of the great custodians of Southern Rock’s memory — a keeper of sound and fact, ensuring that names like Duane Allman, Dickey Betts, Warren Haynes, and hundreds of others aren’t just in liner notes, but living parts of Macon’s bloodstream.

Over in town, Kirk and Kirsten West have done that same work in a different language — saving the Allman Brothers’ Big House, opening its doors to the world, and filling it with decades of photographs, tapes, posters, and artifacts so the story could keep being told. Kyler’s own life runs straight through those Big House rooms: hosting parts of GABBAfest on the lawn, producing and hosting The Whipping Post Big House Radio Hour, and standing in Gallery West, swapping stories beneath Kirk’s photographs, able to name nearly every face on the wall. Kirk and Kyler both have preserved the sound with a microphone, records, radio, and tireless memories told as absorbing stories.

Kyler is the first to admit he can’t sing or play a note. But in a way, he’s been composing something larger all along — a decades-long hymn of loyalty, shaped through festivals, friendships, and the thousands of songs he’s helped keep alive.

When he talks about GABBAfest, his eyes spark the way they must have when he was a boy listening to the Allman Brothers’ guitars echo through the trees. He still channels Bill Graham, still tends the details, still gets that knowing look of a man who believes that good music — and good people — deserve reverence.

And when he tells stories about the Skydog Festival benefiting Daybreak, or about planting trees at the ABB graves at Rose Hill, it’s clear that for him, the music and the mission are inseparable. Kyler’s body has given him more than his share of trials, but the man is powered by a steady beat that refuses to quit. The pulse that first reached him down those power lines in the early 1970s is still inside him.

In the quiet moments, when the house settles and the turntable spins, you can picture him leaning back, eyes half closed, listening to some rare track — maybe one he recorded himself, maybe one from a show long gone. Imagine how he smiles a little. Because he knows: the sound survived.

And because of Kyler, it most surely always will.

Why Kyler Is Held Here

Kyler Mosely is Held Here because he witnessed Southern Rock up close and chose to keep it breathing. He nurtured the music in all the ways that rarely get documented: the rehearsals, the lineups, the backroad gigs, the basement tapes, the players who didn’t make the headlines but shaped the sound. He recorded what might have vanished and passed it all forward with generosity — understanding that stories only matter if they’re shared.

Where the ABB formed branches that spread across the world, Kyler remained at the roots — staying close to the source, tending the local circle, quietly inviting younger musicians into it. Through GABBAfest, Skydog, The Whipping Post Big House Radio Hour, and a thousand small, uncredited moments, he has helped keep the music active rather than archived.

He reminds us that Macon’s musical history doesn’t survive because of museums or collections alone. It survives because it lives in people who care — in the keepers, archivists, hosts, and fans who never stop showing up and sharing what they know — people just like Kyler.

“Pony Boy” at Skydog Festival — Sonny Moorman and Ken Wynn trade dobro lines, one warm and sliding, the other bright and blue, while Ethan Hamlin fills the air on keys, backed by Gary Porter on drums, Dr. Rob on congas, and Eric Wynn on bass. At the edge of the stage, Kyler Mosely films and nods along, and behind the players, Willie Perkins sits in a folding chair, quietly watching another generation light up the crowd. A song full of handclaps, whistles, and sunshine, played inside a circle of history.

About the Author

Cindi Brown is a Georgia-born writer, porch-sitter, and teller of truths — even the ones her mama once pinched her for saying out loud. She runs Porchlight Press from her 1895 house with creaking floorboards and an open door for stories with soul. When she’s not scribbling about Southern music, small towns, stray cats, places she loves, and the wild gospel that hums in red clay soil, you’ll find her out listening for the next thing worth saying.