Newt Collier: A Life in Full Breath

Held Here: Presence in Profile is a series highlighting the artists, archivists, entrepreneurs, and visionaries who have shaped Macon’s cultural identity. Each subject is someone who planted roots and, through their work and presence, have helped preserve the city’s creative spirit for the next generation.

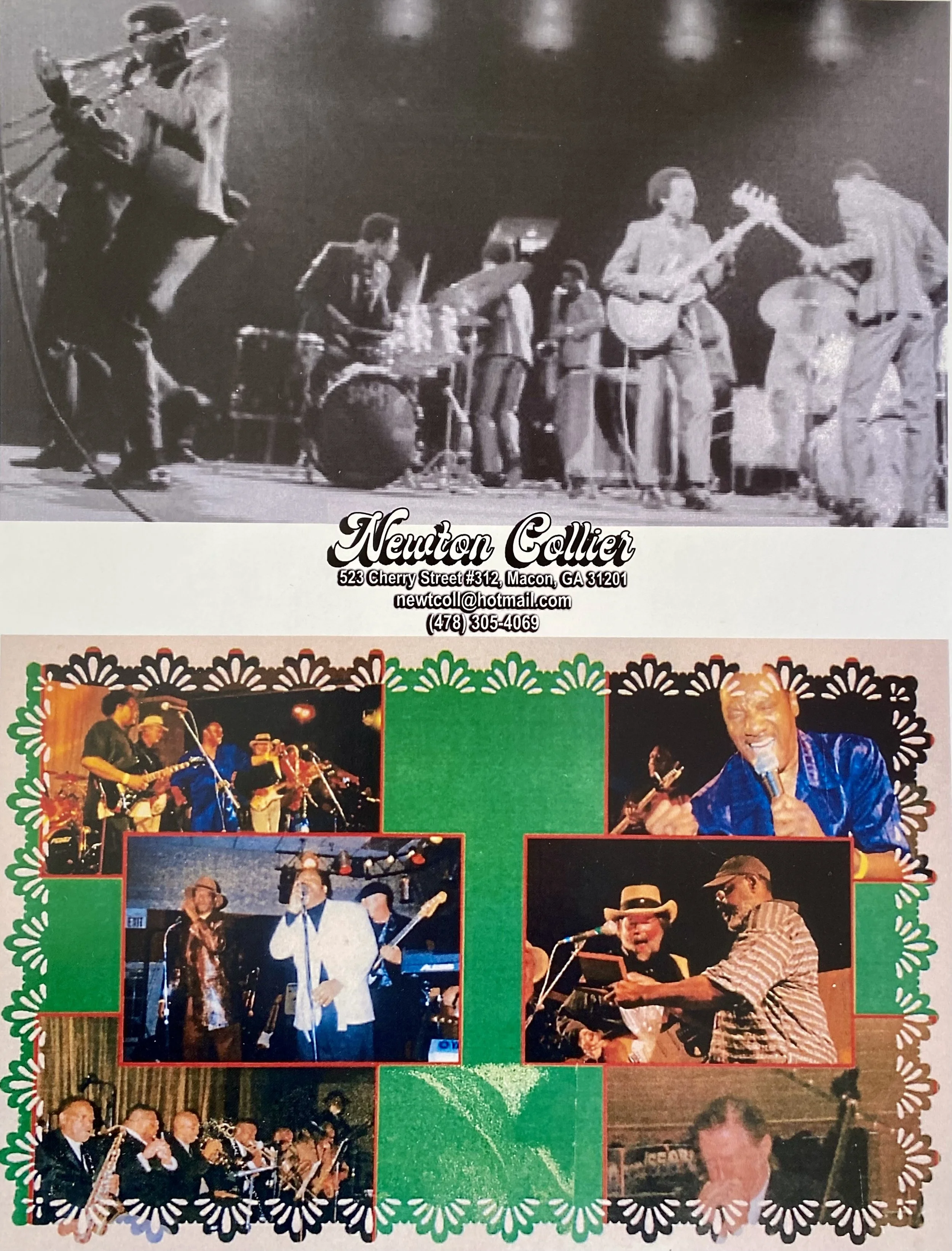

This installment features Newton “Newt” Collier, trumpeter, teacher, and walking testament to Macon’s enduring rhythm. A Ballard Hudson High graduate who once toured the world with Sam & Dave, Collier carried the sound of soul from the Apollo to the Fillmore, from Ed Sullivan’s stage to Madison Square Garden, from television studios to the heart of Cherry Street and every hard mile in between. After surviving a shooting that nearly ended him and his horn-playing career, he rebuilt his life — through recovery and an instrument that let him breathe music again — and then returned to his hometown of Macon, where he has spent decades collecting bits of his musical and family history and other Macon musicians’ stories while encouraging younger players to keep on keeping on.

Now eighty, Newt is still a fixture in downtown Macon; historian, encourager, and charmer. His story is one of reinvention and return. The soul of Macon may be stored in archives and on plaques, but it’s also carried by Newt as he keeps showing up and making room for others.

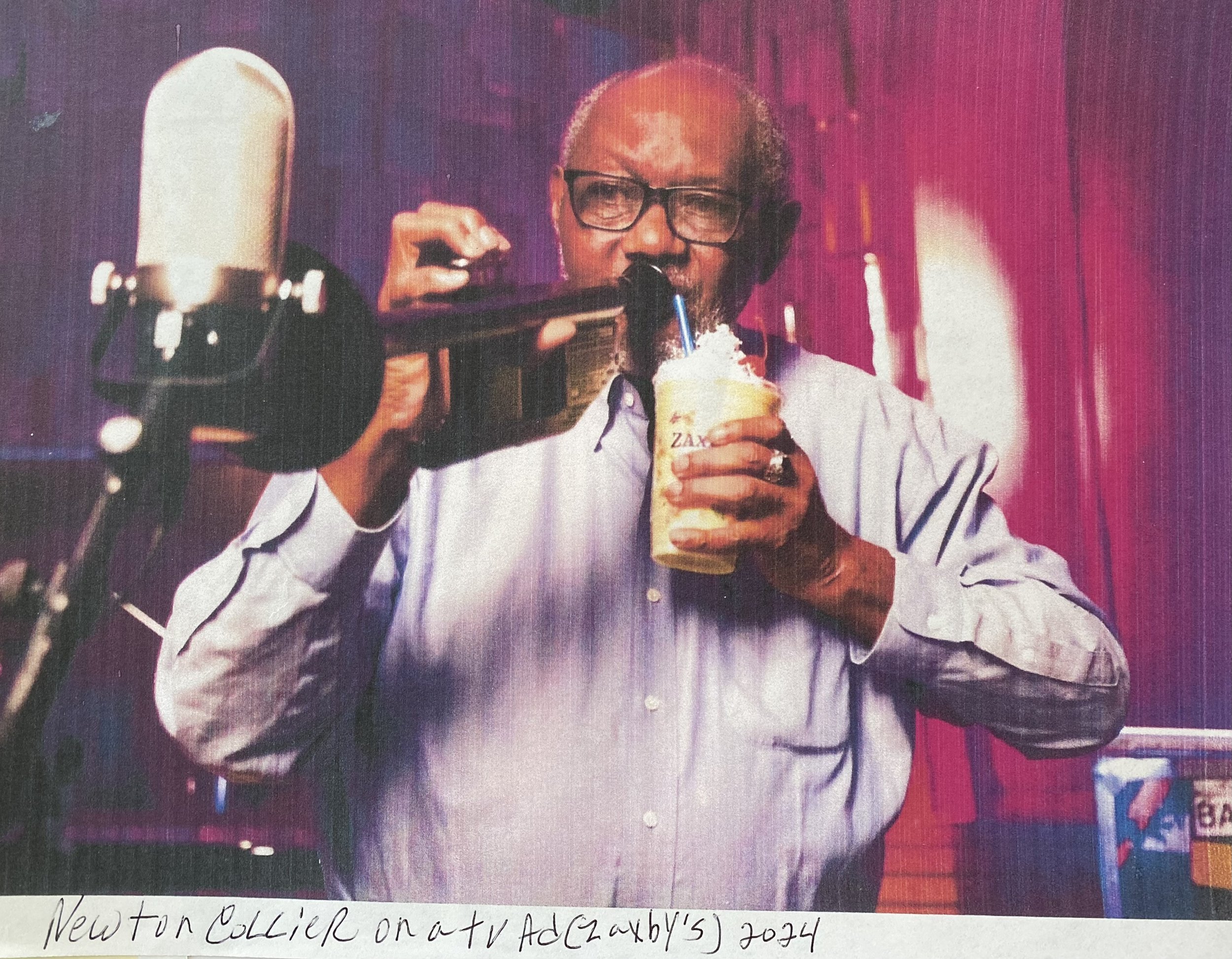

Newton Collier plays his E.V.I. trumpet in Capricorn Studio A Sound booth.

The Macon Newt Remembers

“They had the largest booking agency in the South,” Newt recalls, referring to the Redwal Records operation run by partners Phil Walden and Otis Redding in the 60s. “You had Percy Sledge, Joe Simon, Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, William Bell, Solomon Burke—just name the artists. Think about it: sixty of them being booked out of one little place.

“That’s how Macon became a mecca. Bands came here to sign contracts and work out of here. And you had the nightclubs to support that level of bands coming into town. We had tons and tons of nightclubs up and down Poplar Street; just a whole row of clubs. Cotton Avenue had four or five clubs. Mulberry had a couple. Music was everywhere.

“And they also had Macon Recording Studio—James Brown’s studio—located in the Grand Opera House annex, in back, at the old Georgia Hotel on Mulberry Street, in front of what they called Guy White. Artists would come through town and lay down basic tracks there. They called it the James Brown Studio until it moved in the early ’70s to what is now Jones Funeral Home. The door James Brown used to write his phone numbers on is still there.”*

This was the city Newt came of age in—a working music capital where Black musicians didn’t just pass through history, they built it.

From Macon, those roads led outward to other musical hotspots, most often to Memphis, where Southern soul was being refined inside a converted movie house.

Stax Records— Trust the Groove

The building on McLemore Avenue in Memphis doesn’t look like a recording studio because it wasn’t meant to be one. It was a movie house first, and never quite forgot it. The floor still slopes the way it did when people sat in the dark watching pictures flicker; the control room perches where a balcony used to be, overlooking the musicians like an old projection booth repurposed.

Sound doesn’t behave itself here at Stax. It travels and leaks. It learns its way around corners.

Stax is unusual in that way and others, owned by two white Memphians, Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, but run as a fiercely integrated shop where Black artists, white engineers, and working musicians share the same rooms and the same risks.

Newt stands in the hallway with his trumpet case at his feet, the latches worn smooth. The case leans against a cinderblock wall painted black, paint scuffed where a hundred other musicians have leaned the same way. You don’t wait in silence at Stax Records. Silence doesn’t exist. There’s always something seeping through—an organ warming up, a drummer testing a snare, a bass line looping while someone decides whether it’s right yet.

A buzzer chirps and someone behind glass calls out, not unkindly, “Hold it—don’t move.” A reel clicks. Tape rolls.

This place is built the way old houses are built—tongue-and-groove tight. Each part fitted to the next so closely you don’t notice the seams unless you’re looking for them. The musicians are the same way. One slides into the next, each holding the other in place. No one grandstands. The song only stands because everything else locks together.

Newt knows that posture. He learned it early. You don’t rush the room. You listen for where you fit.

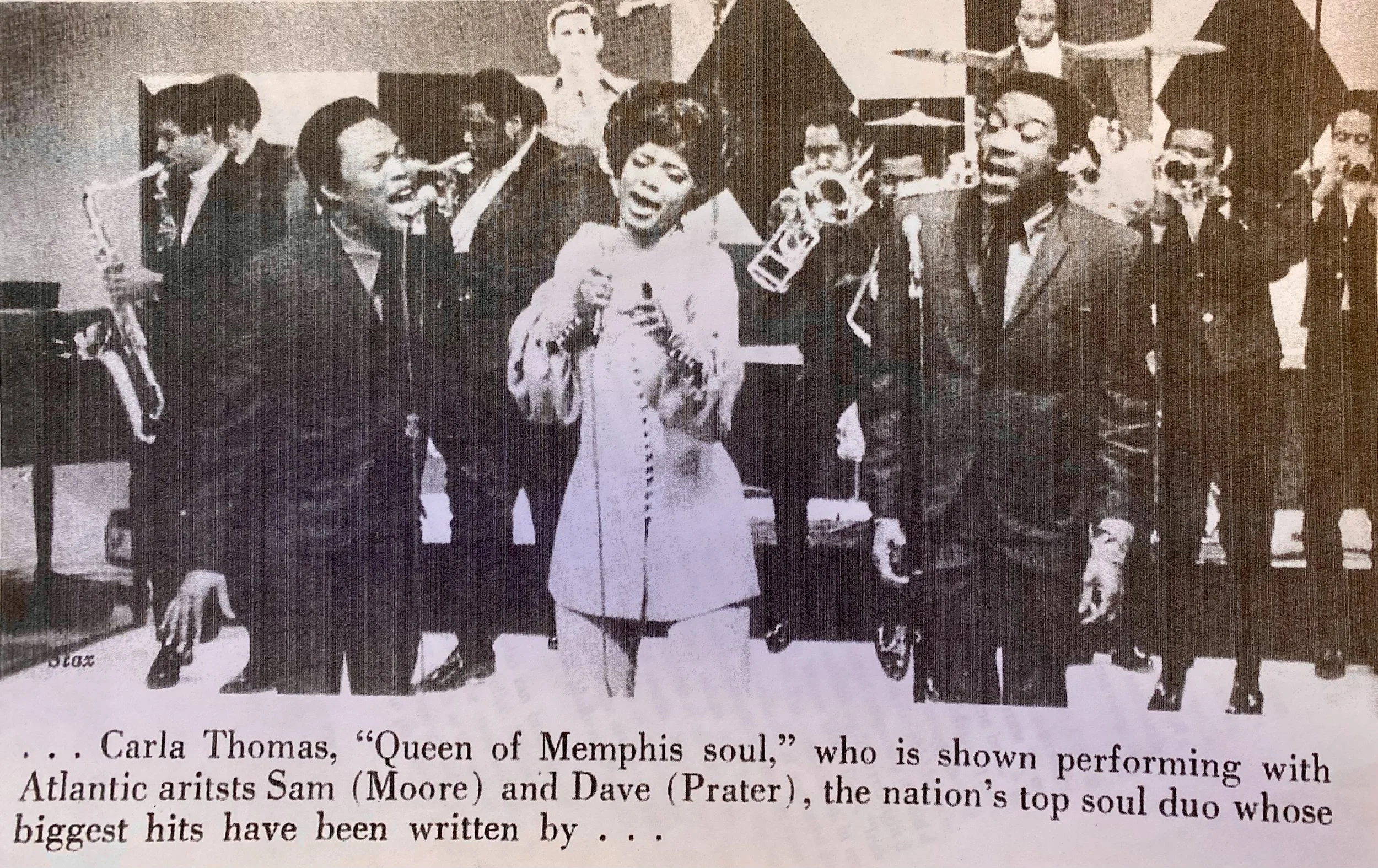

Down the hall, a door opens and closes. Carla Thomas passes by with a smile and touch to Newt’s shoulder. They share stages these days, Carla singing with Sam & Dave while Newt keeps the choreography and trumpet moving. She knows where the center of every song is and isn’t afraid of it. Further in, Booker T. Jones sits at the keys, hands resting, listening more than playing. When he does play, it won’t be many notes—but they’ll be the right ones.

Newt knows Booker T. & the MGs — Duck Dunn on bass, Al Jackson Jr. on drums, Booker T. at the organ, and the Memphis Horns just down the hall — are the spine of it all, holding Otis, Sam & Dave, and Carla Thomas in a sound that feels both raw and indestructible.

Another voice drifts from the control room, measured and exact. Steve Cropper doesn’t waste language. He doesn’t have to. Everyone here understands what again means. Again means closer. Again means tighter. Again means trust the groove.

The building helps. There are no isolation booths the way New York studios have them. No walls thick enough to keep one sound from knowing about another. Everything is recorded live, in the open, the way church music is—call and response, breath to breath.

The Memphis sound.

The engineers know how to balance it so every instrument keeps its shape. You can hear the trumpet separate from the guitar, the organ breathing behind both, the rhythm section holding the whole thing steady like a metronome.

Newt shifts his weight. The trumpet valves click softly under his fingers, a habit more than a necessity. He’s been hanging like this often—listening, ready when needed. Sometimes a horn section calls for one more voice. Sometimes a line wants lifting. Nobody makes a speech about it. A head nods. Newt steps in.

He catches a glimpse of Isaac Hayes moving through the room—tall, contained, already carrying more gravity than noise. Hayes and David Porter are reshaping songs from the inside out, shifting them away from polish and toward something more alive, more driven. Gospel without the church walls. Sweat without apology.

Another buzzer. Go!

Newt lifts the trumpet, steps into the room, and finds his place—by feel. He doesn’t need instructions spelled out. The groove tells him where to stand. When he plays, the sound doesn’t sit on top of the song; it slots into it, clean and sure, tongue into groove.

Out in the hallway, life keeps moving. Someone laughs. A coffee cup clinks against formica. Tape rewinds with a soft whir. This is how records get made at Stax—not by spectacle, but by accumulation. By those who show up and listen hard.

Years later, people will name the singers and the songwriters: Sam Moore, Dave Prater, Jim Stewart, Solomon Burke, Isaac Hayes, Otis Redding… They’ll talk about hits and charts and moments when the music crossed over. They’ll call Sam & Dave Double Dynamite and The Sultans of Sweat. They won’t talk much about the Stax hallway, or the sloped floor, or the way sound traveled through walls that weren’t meant to hold it. But that’s where Newt learned what mattered: that music, like a good building, holds when every unseen piece does its job.

When the song locks in, and everything fits onto the tape for posterity, Newt can feel it in his fingertips, even if nobody ever says his name.

“Music is the soothing soul of a lot of things,” Newt says. “For one thing, music put a lot of people together. It put Otis Redding and Wayne Cochran together. That’s a good combination. It put Booker T. & the M.G.’s together—that was a racially mixed group.

“It put Macon, Memphis, and Muscle Shoals in the same breath for a lot of musical people. Music was the mecca of the city, of the town—and music was also the soul and the heart of the civil rights movement. Everybody had a song.”

In a later interview with Macon Journalist Clarence Thomas Jr., Newt spoke about why the song “Soul Man” holds such meaning for him, explaining that the song traced back to painted signs on Black-owned businesses in Memphis during the unrest following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. “It’s big to me,” he said. “Most people don’t associate that song with the civil rights struggle, but it means a lot to me because of its roots.”

Newt watched as music brought people together again and again in Macon, as new sounds and new faces joined in, including the Allman Brothers Band after signing with Capricorn Records in 1969.

“To be honest with you, when I first saw them come to town, I said, ‘What?’” Newt laughs. “We were used to performing in suits and ties. Then here come these guys with long hair and all kinds of clothes. Folks would stop what they were doing and say, ‘There go them hippies.’ They weren’t the most welcomed people at first. But once they started going to the bank, they got welcomed real quick. Something about green money breaks down barriers.”

Trumpet Man Newt Collier Today

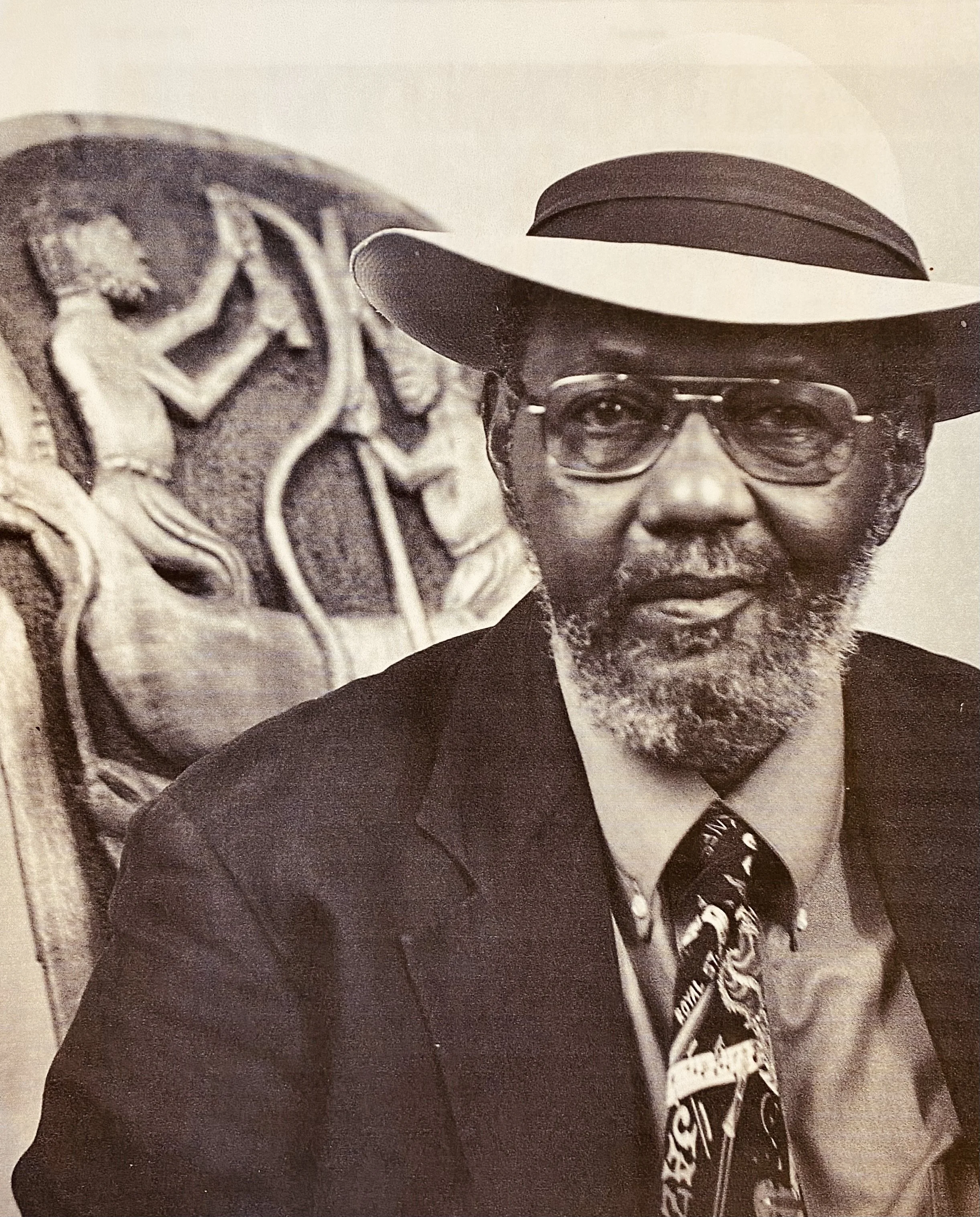

These days, when Newt shows up at a Macon event, the room doesn’t break stride — it simply adjusts to include him. Folks nod, drift over, clasp his hand, pull him into conversation. Not because he demands attention, but because he’s been part of the city’s musical bloodstream for so long that acknowledging him feels as natural as tapping your foot to a backbeat.

When Newt walks into a room he’s treated like kin, not celebrity; someone who has been in the room for sixty years and might just be in it for sixty more.

He was at the All Blues festival last fall, taking in the scene. When I saw him, we greeted each other without words — just a shared smile and quick fist bump as Lil’ Willie Farmer played on stage. It was enough to show kinship.

Newt belongs to Macon’s past and its current pulse. He still posts videos on Facebook, cheers on other musicians, shows up for luncheons, and slides into musical conversations, another language he’s fluent in.

Just this year, the Macon Arts Alliance honored Newt with a Legacy Award — the same night Grant’s Lounge received theirs. When Newt stepped up to accept his award, he didn’t reminisce or make it about himself. He looked straight at the audience sitting in the Mill Hill Community Arts Center, pointed to the stage behind him, and said, “Y’all need to use this stage, have bands play here on weekends. Every weekend. Showcase our town’s talent.”

That was all he said. It wasn’t a plea; it was direction from a man who’s spent a lifetime watching great musicians be underused. The crowd agreed through applause.

Another deserved accolade arrived in October 2025, when the Macon–Bibb NAACP honored Newt with its Harvey Lee Hollingshed Music Service Award, presented at the organization’s 53rd annual Earl T. Shinhoster Freedom Fund ceremony. It wasn’t an award for a hit record or a headline moment — it was recognition for a lifetime of service to Black music, Black memory, and Black community. For Newt, who has always believed that music is a form of care, the honor carried a particular weight: it placed him not just in the story of Macon’s sound, but in the story of Macon’s service.

He has also been recognized by the Tubman Museum, which exists to preserve African American history in Middle Georgia — the same work Newt has been doing in human form for decades.

Newt’s horn has threaded itself through some of the most enduring sounds of American soul, but his road into that engine room was local before it was legendary. After Otis Redding left Johnny Jenkins & the Pinetoppers to form his own band, Newt joined the Pinetoppers and worked that circuit for several years — the kind of apprenticeship where you learn arrangements by ear and get good fast or go home. Then Phil Walden, who’d been watching Newt’s steadiness up close, suggested he join a new act Walden was booking: an energetic pair of entertainers from Miami called Sam & Dave.

Newt likes to tell it straight. When Phil Walden called to ask if he would want to perform with Sam and Dave, Newt remembers asking, simply, “Who?” He hadn’t heard of them yet. That’s how it sometimes worked back then—opportunity arrived before reputation.

Sam & Dave, with Newt onboard, played small gigs around Macon until “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” broke out as a hit. From there, Newt moved into the Stax machinery in full stride — “Soul Man,” “Hold On, I’m Comin’,” “I Thank You,” “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby” — night after night, stage after stage, mile after mile.

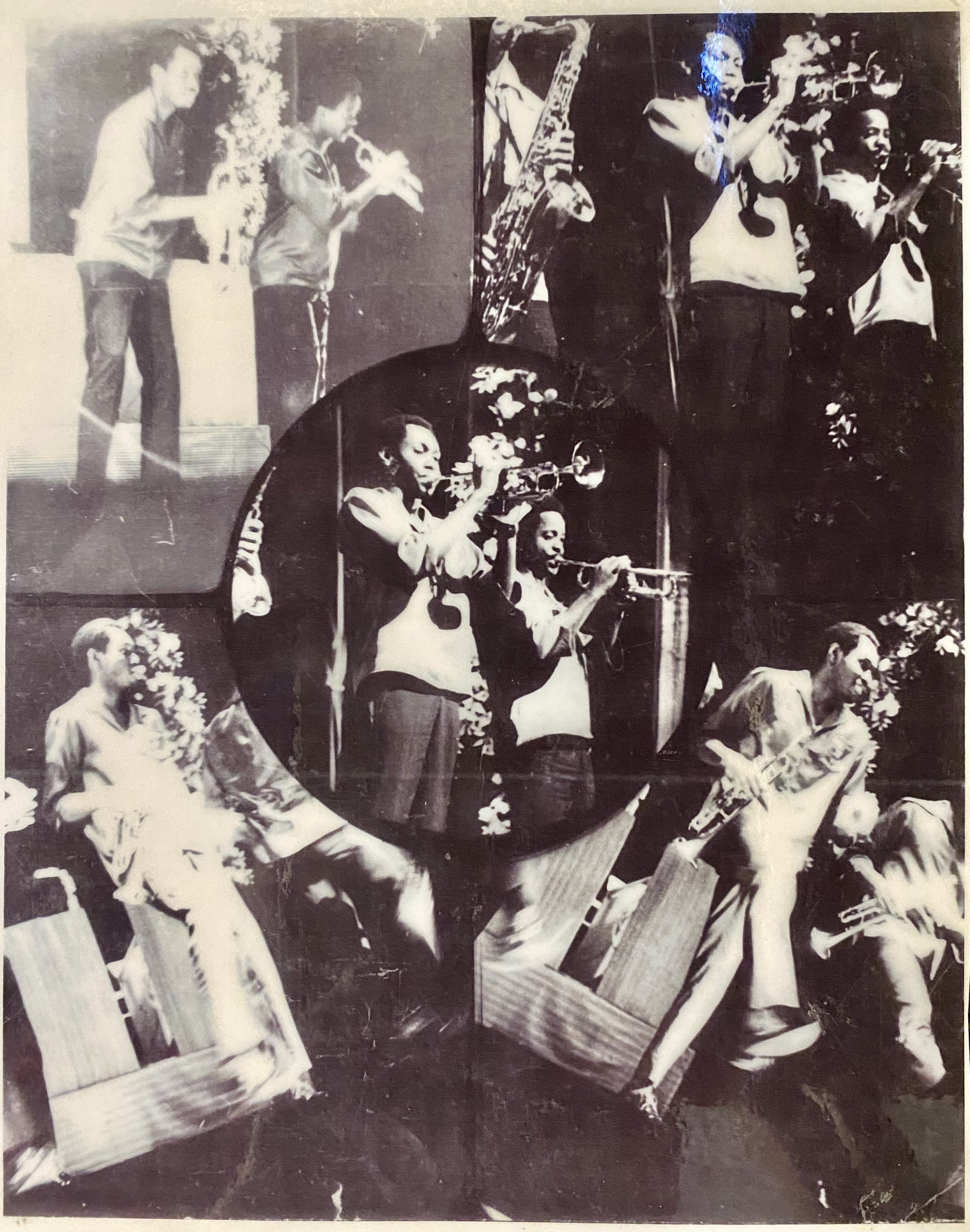

Beyond the marquee stages, Newt turned up in studios, clubs, and multi-artist revues across the country and overseas, lending his warm, punchy phrasing to artists from Otis Redding and Arthur Conley to ZZ Hill, Junior Walker-style horn men, and Little Richard. He wasn’t a showboat; he was the kind of horn player who made the whole band stand up straighter — precise when the groove needed discipline, loose when the spirit needed lifting. And usually clowning around to keep spirits light.

Musically, Newt’s style exemplified the sound of 1960s Southern soul — punchy but fluid horn lines, a keen responsiveness to the vocalists’ emotional dynamics. His playing had a grounding in rhythms that bridged gospel, blues, and early R&B. Colleagues and critics alike remember him less as a flashy soloist and more as the kind of reliable, soulful sideman whose presence gave depth and warmth to every performance — the kind of musician who makes “the song” sound bigger than just the singers, without ever overshadowing them.

And yet, Newt was anything but solemn. Onstage, he was playful, even clownish by his own account, delighting in the joy of performance and the laughter it could spark. Egged on by the larger-than-life showmanship of Sam & Dave, he sometimes showed out — even playing trumpet and trombone at the same time — not to steal the spotlight, but to loosen the room and remind everyone that soul music, at its heart, was meant to move bodies as much as it moved hearts.

What survives of his recorded legacy is scattered across tours, broadcasts, and sessions where sidemen rarely received credit, but Newt the artist has always been there: a working musician who still carries soul wherever he goes.

He’s still pushing Macon forward. While society often tries to tuck elders out of sight, Newt stands there reminding everyone that seasoned musicians aren’t relics — they’re resources.

He’s especially vocal about the fire still burning in the Community of Older Music Professionals, the group called COMP, founded by Tim Griggs at Capricorn Studios. Newt nor Tim are shy about telling the city to make room for older music professionals, many who are still performing regularly in Middle Georgia. Not because Newt wants to play on a stage every weekend — he’s long past that hustle — but because he knows how much wisdom and beauty sit in the laps of men and women who still bring their music to eager audiences.

Newt doesn’t crave a regular bandstand or late-night gig; that yearning only comes in short waves these days. He plays a few times a year, on his own terms. What he really wants is for older and younger musicians to have opportunities, for Macon to keep hearing itself.

The city is quieter now than the heyday of Capricorn and soul revivals that once roared through these streets, but Newt hears rhythm where others hear routine. When you talk to him, you can feel how the notes still move under his skin — as recognition. He’s lived enough for ten lives — toured with Sam & Dave, backed Otis Redding and his peers, survived a wound that could’ve silenced him — but these days, it’s not about the legends he played beside. It’s about the city he stayed with.

In a world where fame tends to drift north and the spotlight moves on without mercy, Newt Collier came home and stayed right here in Macon, horn in hand, waiting for the next upbeat life might offer. And in doing so, he became something Macon strives to celebrate — not a myth, but the embodiment of the music. And a well-loved soul.

The Present Tense of a Legend

Macon’s got its share of monuments — Otis’s statue facing the river, the Allman graves up on Rose Hill, the endless vinyl in every record bin — but Newt is something rarer: a living monument that moves. He doesn’t sit still long enough to gather dust or legend.

These days, his name is even set into the sidewalk outside the Douglass Theatre on their Walk of Fame. The Douglass Theatre, built in 1921 by Charles H. Douglass—Macon’s first Black millionaire—once anchored the Chitlin’ Circuit and still opens its doors for performances and films, a cherished throughline of Black cultural life. The theater, along with Macon The Stage, honored Newt with his star for making Macon a Mecca for music lovers.

Even though his image is engraved in concrete, Newt still moves through town like a neighbor, not a statue.

In fact, his image rides the streets of Macon, featured on a city bus as part of a public tribute to the city’s “Macon Music Masters”—a moving gallery that places his photo alongside figures like the Allman Brothers Band, Robert Lee Coleman, Chuck Leavell, R.E.M., Johnny Jenkins, Arthur “Bo” Ponder, and Phil Walden. It’s a reminder that Macon’s music history is still moving through town, still moving people—emotionally and spatially.

He treats social media like another stage where his joy is connective. He’s reposting gig flyers, birthdays, and African-American stories, along with the occasional post about memories from his days with Sam & Dave or Otis’s old crew. His posts are dispatches from a man still in love with his city and its potential for live music. Younger musicians message him, old friends tag him, and strangers who meet him once remember the hug he gave them. He is, in the truest sense, held here in Macon by the people who know: when Newt shows up, the room gets lighter.

If you want to find Newt in the wild, don’t look for a velvet rope — look for a doorway with music coming out of it. His favorite spot is the Hummingbird on Cherry Street near MLK Jr. Boulevard, where the space still feels like a real room, not a production. He’s also loyal to Grant’s Lounge and the Vice Club, both on Poplar Street; drawn to places where the groove is close enough to touch and he can relax into the shadows if he feels like it.

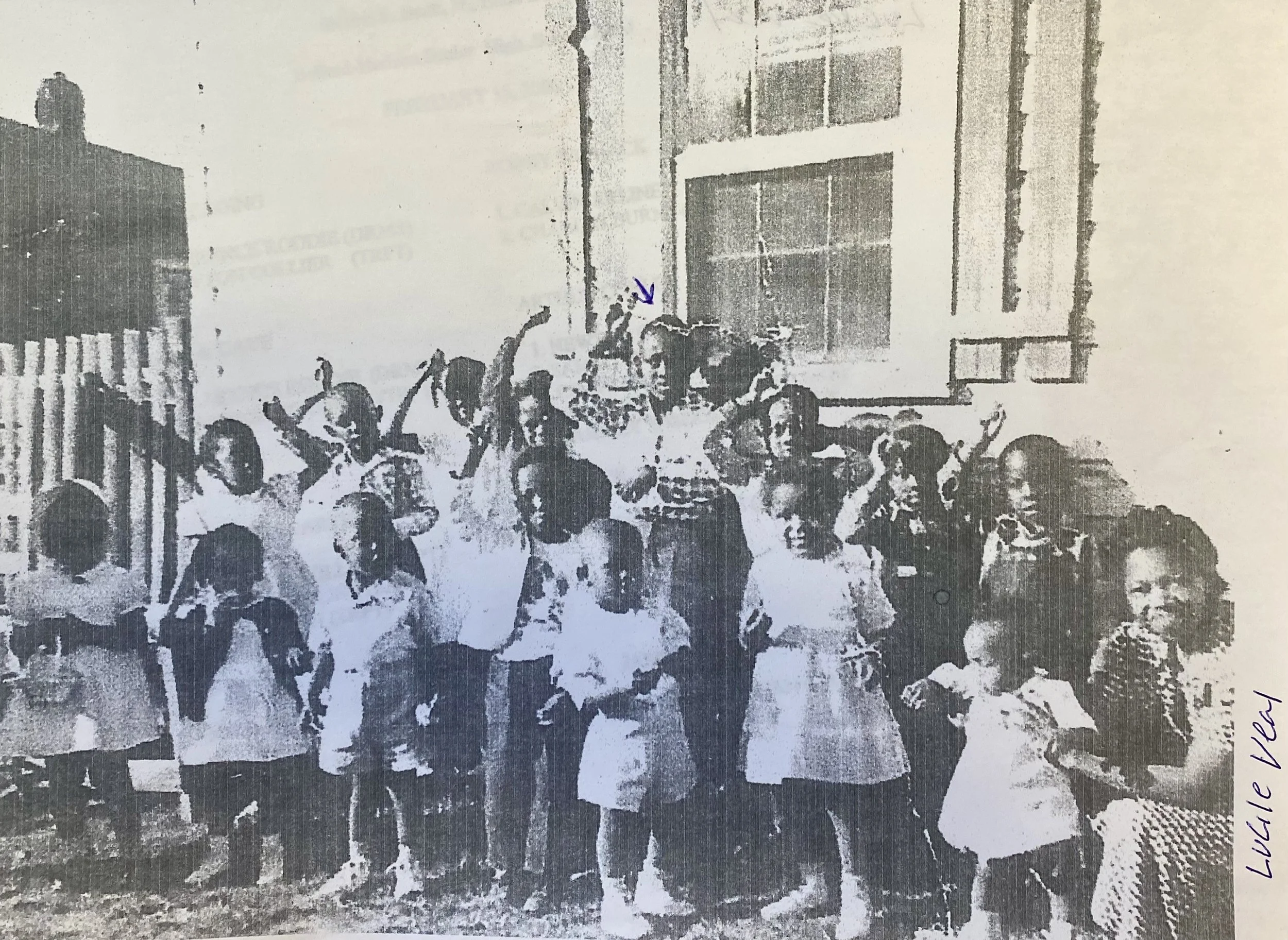

Newt, center, surrounded by siblings, cousins, and his mother, Lucile Birdsong Collier Veal.

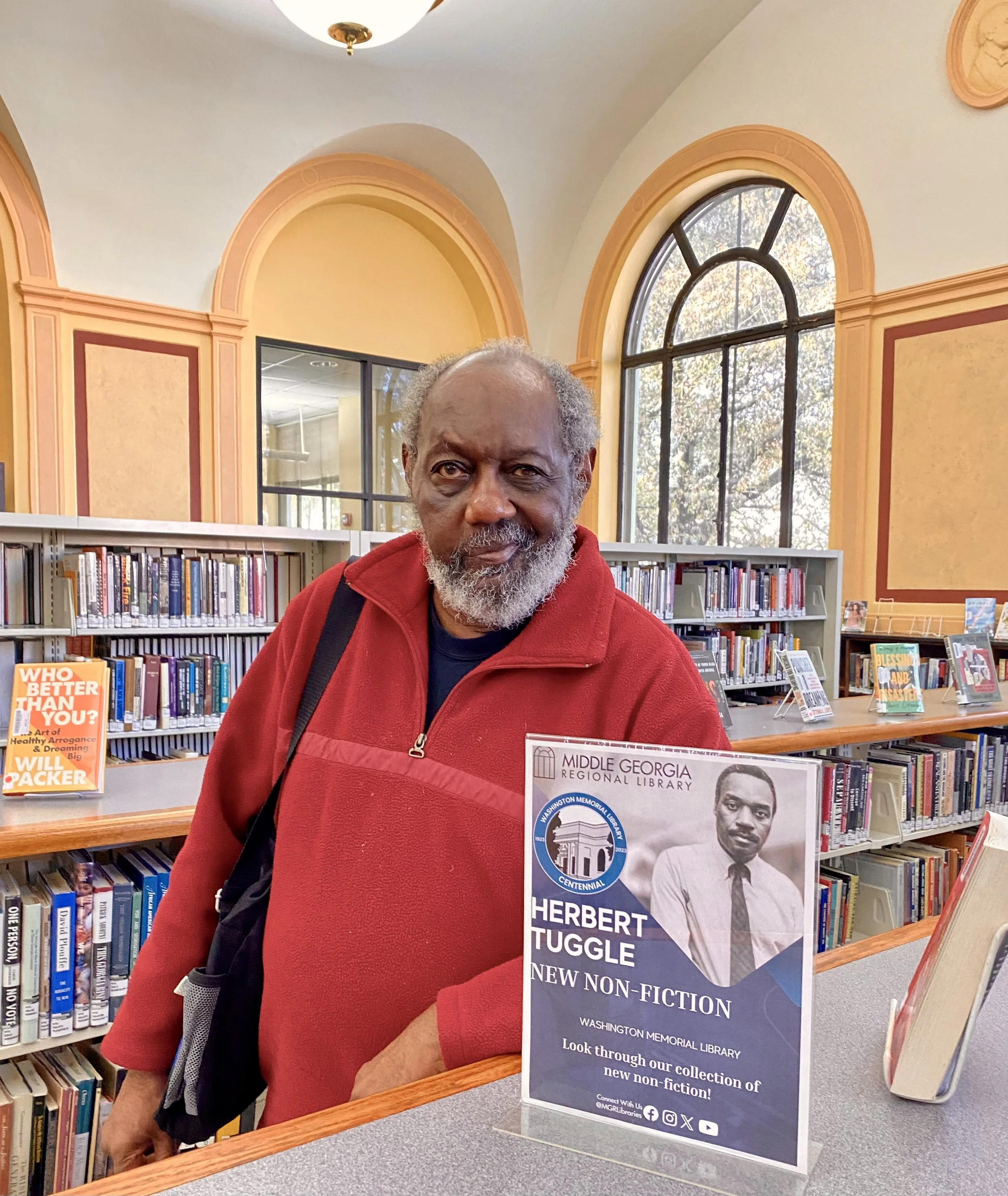

Eager for knowledge since he was a kid, Newt is still learning. He has always loved libraries—loved them the way some people love barbershops or front porches: as places where information travels, elders hold court, and your mind can grow without asking for permission. He spends so much time at Washington Memorial Library that the staff knows him by name. He drifts into the Genealogy Room like it’s a second home base, carrying folders for safekeeping, to be added to the record—his own archive, waiting for future historians and writers to use.

The day he and I met there, the librarians were rearranging shelves, and the books Newt wanted to show me weren’t where they’d always been. He paused, genuinely thrown, then laughed and began the slow work of learning the stacks all over again. And he did find those books for me to see.

Upstairs, one of the books he asked the librarian to track down was I Sought My Brother: An Afro-American Reunion, written by S. Allen Counter, a Harvard professor originally from Americus, Georgia. Newt had met Counter years earlier through a mutual friend while visiting the MIT library in Boston, and the man—and his work—have stayed with him.

The book, which documents Counter’s journey to Suriname and his profound connection with an African-descended community that preserved its culture intact for centuries, was waiting for us in the Herbert Tuggle Collection. We stood there turning its pages together, Newt and I both drawn to Counter’s search for kinship across time, distance, and displacement. Counter died in 2017, another brick in the wall of Newt’s living memory quietly gone.

Newt’s love of libraries started when he was regularly dropped off at the Amelia Hutchings Library by his mother, Lucile Birdsong Collier Veal, to keep him from slipping downtown to Clint Brantley’s nightclub, where he hungered for music lessons. Named for Amelia Hutchings, a Black woman whose dedication to education helped create a haven for learning in a segregated city, the library joined Lucile in steering Newt toward a quieter kind of power—books, history, and a room full of questions with answers. Rooted in Macon’s thriving Pleasant Hill neighborhood of that time, Hutchings was a place of intention and care, shaping Black youth like Newt.

Along with enjoying the books, Newt listened to the library’s jazz records by Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and Dizzy Gillespie, playing along on his trumpet until the notes began to live in his fingers.

One of the people who made the Hutchings Library come alive for Newt was Mr. Herbert Tuggle, a librarian who became his mentor. Tuggle curated a remarkable collection of books by Black authors and about Black life, helping young readers see themselves as part of a longer, deeper story.

When the Hutchings Library closed in 1970, its collection was folded into Washington Memorial Library. Newt followed the books there and, in many ways, has been tending to them ever since. On the library’s second floor, he can still find the lineage that helped raise him in the Herbert Tuggle Collection. Tuggle went on to become the first Black head of reference at Washington Memorial, carrying Amelia Hutchings’ legacy into a new home and a new era.

Newton “Newt” Collier at Washington Memorial Library, standing beside a display honoring librarian Herbert Tuggle— one of his mentors. Tuggle helped preserve and expand Macon’s African American collections after the Hutchings Library merged into the system. Newt has been coming to this library in one form or another his entire life.

Roots: What Newt Inherited

Newt Collier Jr. came from people who had already mastered the hardest work there is: surviving with dignity in a world designed to deny it to them. His family’s roots in Middle Georgia run deep—through Macon, Fort Valley, Montezuma, Barnesville, and Sparta—and were laid down by Black men and women born just after emancipation, or before it, who lived under Jim Crow’s daily humiliations and unspoken threats.

This was not the same public world whites occupied. Deference was required. Silence was often safer. One wrong look, one misunderstood gesture, could cost a job—or far worse. Simply raising children, holding work, and staying intact made these people heroes.

Newt’s mother, Lucile Birdsong Collier Veal, was born and raised in Macon. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Fort Valley State College and became a public-school teacher until retirement.

Mrs. Lucile Birdsong Collier Veal

Newt’s mother.

On his mother’s side, Newt’s story centers on his grandmother, Malinda Williams Birdsong, born in 1891 in Sparta, Georgia, Hancock County—within living memory of slavery. Widowed young after the death of her husband, Eugene Birdsong, Malinda supported her family in Macon as a laundress and cook for white households, labor that kept Black women economically afloat while reinforcing their enforced invisibility.

Malinda never made it past the third grade, yet she raised children who became educators. By 1940, her household included two grown daughters, Lucile and Carrie Mae, both teaching in Macon’s public schools, and a son, Elijah, working as a chauffeur—evidence of a quiet, determined push toward stability and self-sufficiency.

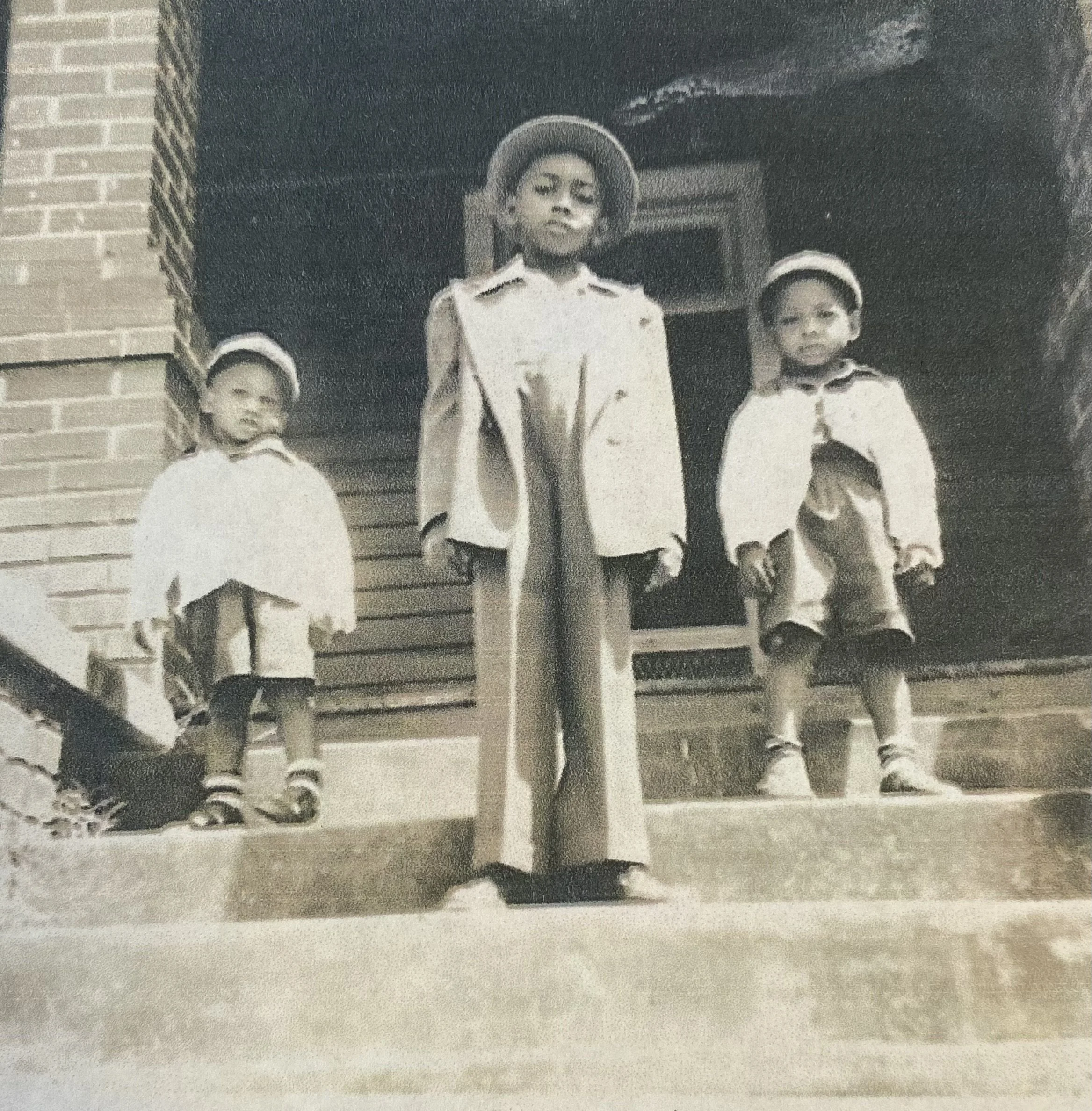

Newt was five years of age when his parents divorced and his father, Newt Sr., left Macon. Lucile, her sister Carrie Mae, and Malinda remained the steady presence in Newt’s life—watchful, protective, and insistent on structure in a world that offered Black boys very little margin for error.

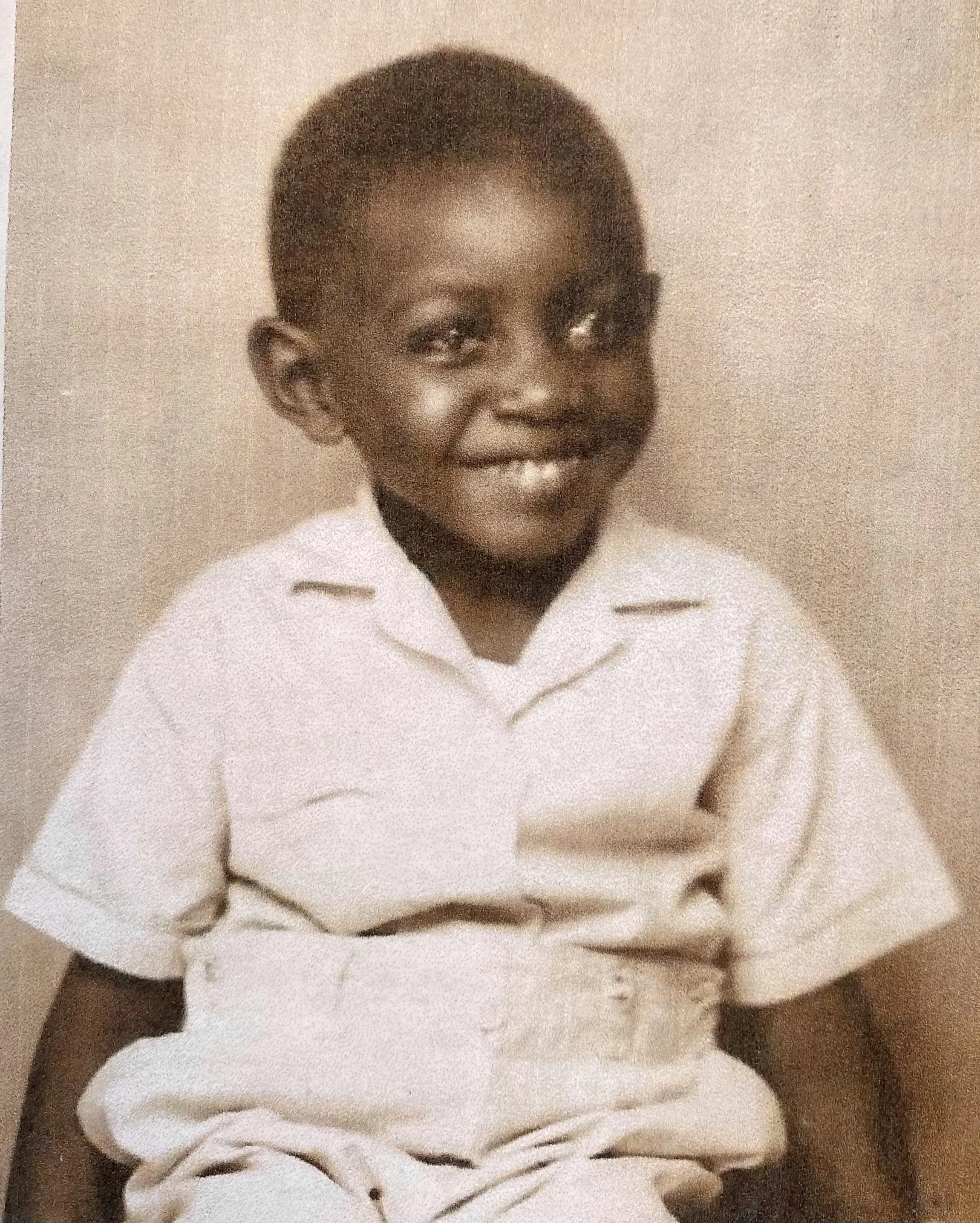

As a baby, Newt battled spinal meningitis and spent years in a brace — his body learning patience. He couldn’t walk for a long time. Lucile nursed him through the meningitis, a serious illness in an era when Black families were often segregated in hospitals and could not assume equal care.

The early restraint of back braces and immobility can leave a mark: it trains a child to listen, to wait, to work with what is, and still imagine what could be. Being on the road years later taught Newt about risk, but his own young body, and the strong women raising him, taught him about persistence.

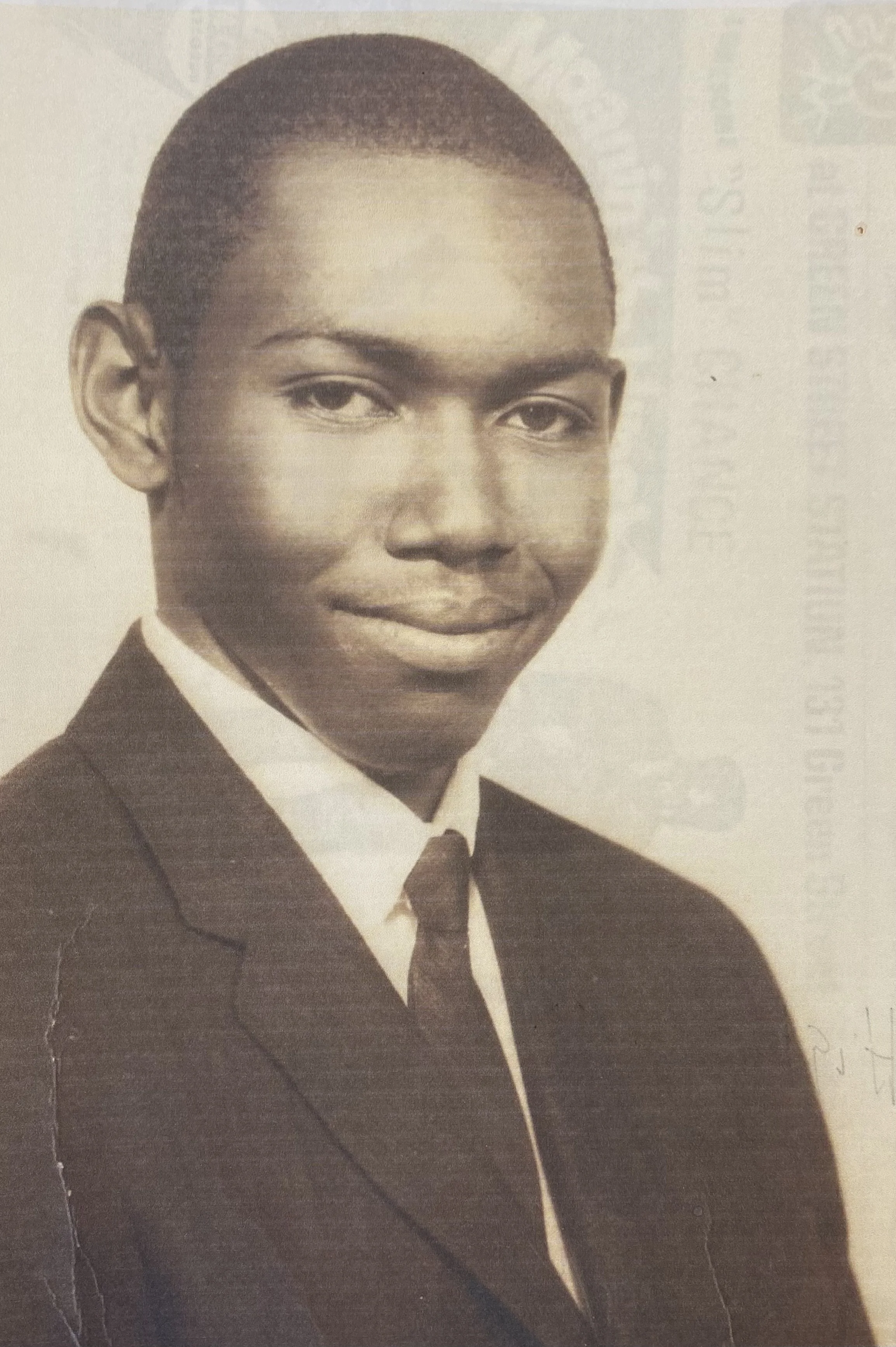

Newton Collier as a young boy, during years when illness required patience and physical constraint—an early lesson in endurance that was quietly shapibg how he learned to hear music.

When Lucile remarried, to William C. Veal, they created a household that bridged two kinds of labor common to Black families in mid-century Georgia: the classroom and the job site. William worked as an oiler on a dragline at the chalk mine, a dangerous, physically demanding job that kept heavy machinery running and left little room for mistakes.

Together, they raised Newt and their three younger children — Maurice, William, and Linda Veal Crawley — in a home shaped by discipline and care—a household Newt speaks of with pride and gratitude.

“William was my daddy,” Newt says. “I was accepted and became part of a whole other family.”

Music ran through the entire Veal household, not just Newt. Lucile played the piano and taught Newt for a while before turning him over to Gladys Williams for lessons. Linda played flute in high school. Maurice and William studied drums. Everyone learned the piano. Newt’s family echoed a broader mid-century family rhythm, when music lessons were simply part of home life shaped by radios more than tv, which was still finding its footing back then. Across communities, music was commonly something people made instead of watched.

With his Grandmother Malinda living in the house just next door, and his Aunt Carrie in the house across the street, Newt had plenty of “homes” and folks to watch over him in Tindall Field.

On his father’s side, the Collier and Marshall families tell a parallel story of labor and endurance. Newt’s paternal great-grandfather, Dave Marshall, would have been born enslaved in the early 1850s. By the turn of the twentieth century, he was working as a farm hand and later as a wagoner for the city of Fort Valley—jobs tied to movement and service.

Dave’s daughter and Newt’s Grandmother, Florrie Marshall Collier, worked as a laundress for white families. Her husband, Bob Collier, cleaned Pullman railcars at the railroad yards in Fort Valley, work that kept the machinery of travel running while denying its workers access to the freedom it symbolized. None of this labor came with security or safety.

Newt Jr. may not have inherited wealth or ease, but he inherited something much more valuable and harder to name: a legacy of work, care, education, and watchfulness—of knowing how to move through the world without surrendering his selfhood. That inheritance would shape how he showed up in Macon’s music scene: attentive, grounded, steady, and deeply committed to community.

The Long Road Home

Newt grew up in Macon’s Tindall Field neighborhood that encompasses Tindall Heights, a community that housed many returning veterans from World War II and the Korean War — men whose discipline, worldliness, and sense of responsibility shaped the children around them. The neighborhood was arranged like a horseshoe, and a boy growing up there in the 1950s knew exactly what that meant: the men would run you around it until you learned stamina, respect, and how to “carry yourself.”

These veterans taught the boys in Tindall Field not just how to be strong, but how to be Black in the segregated South — how to read danger, how to speak when spoken to, when to step back and when to step forward. They taught military drills in the center field, calisthenics before supper, and the quiet art of staying alive in a world that might not care if you did.

Newt absorbed it all.

His mother enforced her own layer of protection. If he walked toward the railroad tracks — the shortcut he wasn’t supposed to take — she knew before he made it home. Neighbors watched the boys like their own kin.

Aunt Carrie reinforced hospitality and presence: when guests came to the house, young Newt was taught to greet them properly, offer a seat, and make them feel welcome until the adults arrived.

And then there was the other training — the kind that drifted through windows and down sidewalks.

“Tindall Field was FULL of musicians,” Newt says. “Still is.”

He grew up alongside guitarist Robert Lee Coleman and singer Arthur “Bo” Ponder—boys from the same streets, shaped by the same long apprenticeship Macon handed out without ever calling it a school. They were friends early on, neighbors, listening and learning side by side before their paths widened.

Robert was mostly self-taught and performed alongside Newt and Arthur when they were young men, before heading out with Percy Sledge, making his mark on “When a Man Loves a Woman,” and later touring the world with James Brown.

Arthur stepped into Johnny Jenkins’ Pine Toppers after Otis Redding left, beginning a career that kept him central to Macon’s music life for decades, until his death in 2024.

Newt and Robert are both still active in Macon. Robert plays local stages regularly and is often at Kirk and Kirsten West’s downtown Gallery West, performing for First Friday crowds.

Growing up, Newt learned music not just in rooms, but over the air. He remembers being drawn to sound—especially trumpet—while listening to Ray Charles on WIBB.

WIBB, the city’s Black-operated radio station, was a constant presence in Newt’s life—broadcasting the sounds, voices, and priorities of Black music into homes and neighborhoods across town. The DJs were tastemakers and narrators, sometimes characters, connecting local musicians to national artists and turning records into events. Voices like Charles “Big Soul” Green, Mr. 5 X 5, Don “Keep on Keeping On” King, and Robert “Mighty Rock” Roberts gave the station its pulse—while women like Bernice “Queen Bee” Cotton and Palmira “Honey Bee” Braswell shaped its tone and authority.

From its studios on Third Street, across from the Bibb Theatre, WIBB helped define how a generation listened. Newt absorbed that world early—the cadence of Black DJs, the sense that music in Macon answered to its own audience.

Macon music had its matriarchs. At six, Newt took piano lessons from Mrs. Gladys Williams—whose home was listed in the Green Book as a safe haven for traveling Black musicians. Her house was infrastructure: shelter, food, safety, and a standard of excellence. Over the years, artists passed through who defined an era—figures like James Brown, Sammy Davis Jr., Eartha Kitt, and Pearl Bailey.

One afternoon, Sammy Davis Jr. stepped out of a Rolls-Royce and let young Newt hold his trumpet. Newt felt a buzz. From that moment, his path was set. He begged his mother for a trumpet, and after she conferred with the manager at Bibb Music Center, she purchased a Conn Constellation for her ten-year-old son.

(Learn more about WIBB DJs with Visit Macon’s oral history video.)

The Apprenticeship Engine

Newt’s education didn’t come from one teacher or one room. It came from a chain of people and places, each adding a layer.

By the time Newt reached Ballard Hudson High School, his musical instincts had already been shaped by night clubs, churches, and living rooms—but it was band director Robert L. Scott Jr. who formalized what Newt had absorbed. Scott was more than a band director or teacher; he was a builder of pathways. Under segregation, he created a disciplined, forward-looking music program that quietly fed talent into the professional world.

Years later, when Macon Magazine documented Scott’s legacy, Newt was there as proof—quoted, photographed, still carrying the lessons. “The learning never stopped with him,” Newt said of Scott. “He wanted the best for his students and to make sure they were on note in the band and beyond.”

Newton “Newt” Collier, photographed by DSTO Moore for Macon Magazine, in a feature honoring band director Robert L. Scott Jr.—the educator who helped transform neighborhood talent into professional musicians.

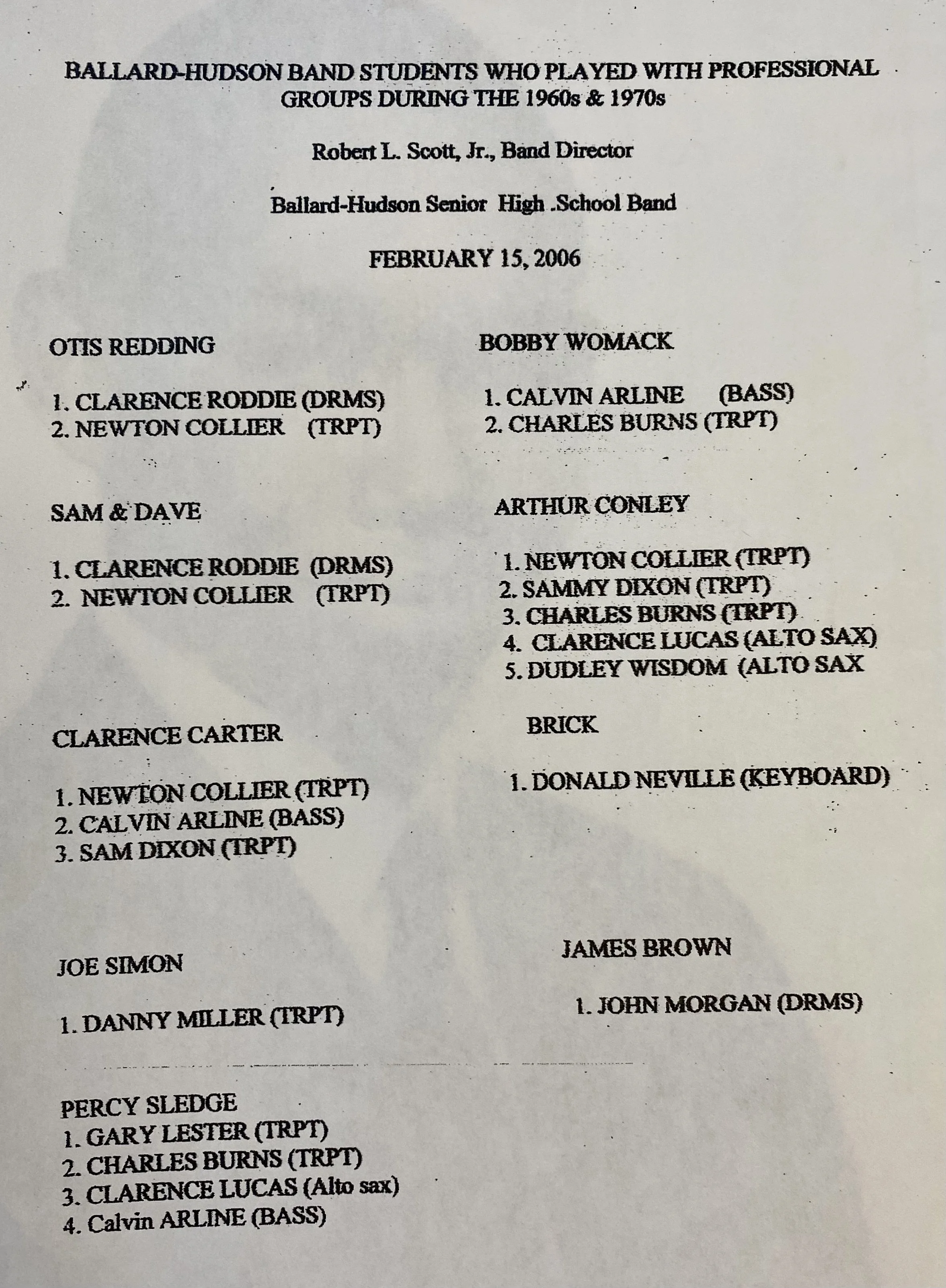

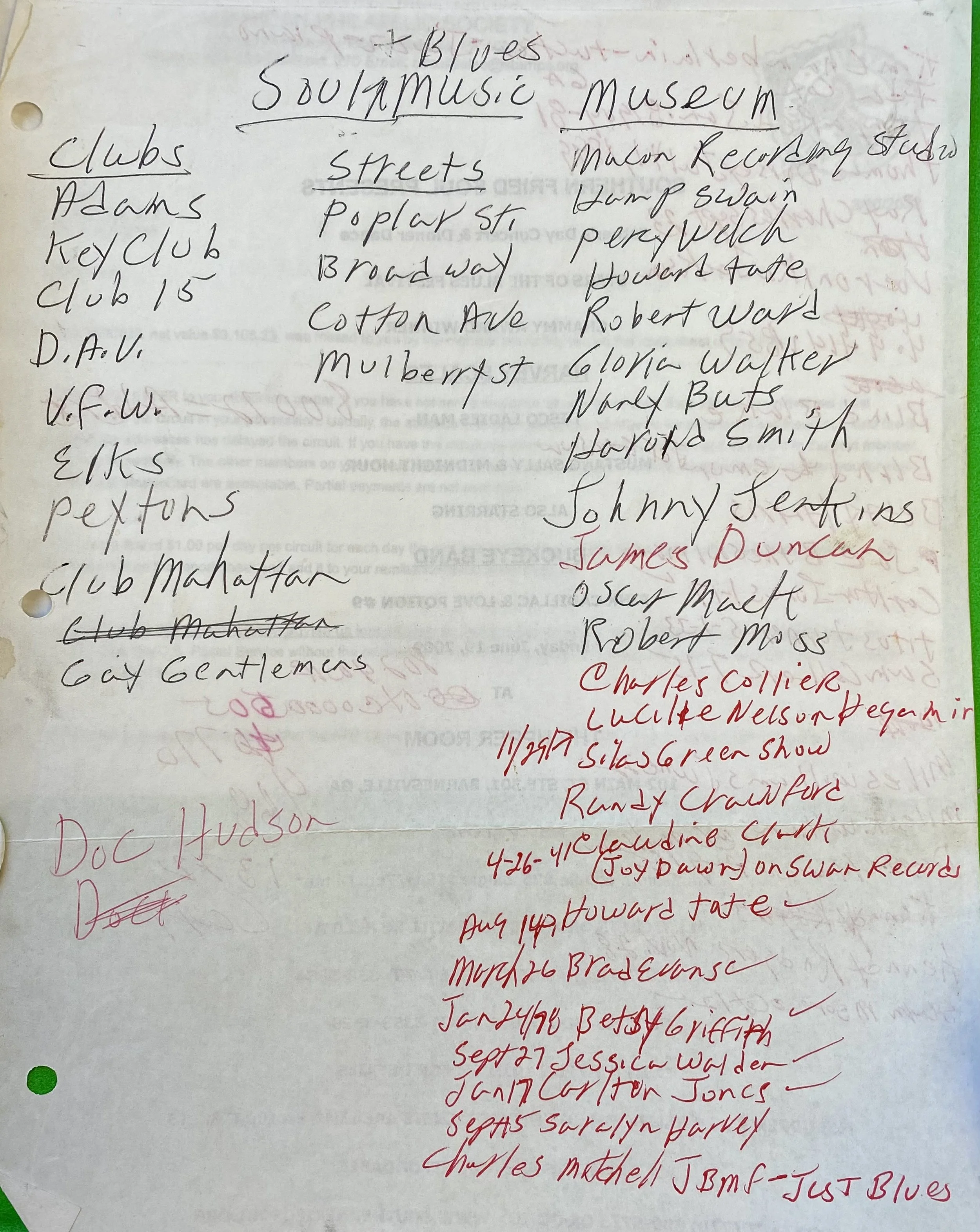

Newt collects information like this list — artists nurtured by high school Band Director Robert L. Scott — to ensure the info is around for future scholars to use.

He tucks the info into files for his archive at Macon’s Washington Memorial Library.

Newt can still point to the porch where Macon music’s future warmed up. On the 1500 block of Campbell Avenue, rehearsals gathered the way weather gathers — rolling in, inevitable. Pat Teacoke had a band with Johnny Jenkins in it. Otis Redding and Johnny would work up material at Morenstein Durham’s house, and Newt — still a kid — would sit on his steps across the street and watch it all happen in real time.

He would sometimes slip over with his Conn Constellation trumpet and listen to their horn player, Obe Kimbrough, trying to match every phrase to play just like Obe.

And then, like a gate swinging open, two young white guys started showing up: Phil and Alan Walden. Alan, Newt remembers, didn’t have much to do at first — so he walked over and introduced himself to Newt. That’s how they met.

It’s not hard to see that porch as a small beginning with a long shadow: Otis headed toward world stages; Phil learning how to build an ecosystem that would eventually become Capricorn Records; Alan discovering what a scene can become when somebody believes in it, and taking that belief to his management of Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Another neighbor, Sammy Coleman, a trumpeter and organist stationed at nearby Robins Air Force Base, became Newt’s unofficial tutor, and later became Otis Redding’s trumpeter, playing lead trumpet on the live album Otis Redding In Person at the Whiskey A Go Go.

“I adopted Sammy as my brother and mentor,” Newt says. “He lived in my neighborhood and most afternoons Sammy would come by my house and we’d walk to the Two Spot, Clint Brantley’s place.”

Sammy took him downtown to hear jazz, taught him nightclub etiquette, and showed him how to keep a crowd on its feet. Trumpeters Obe Kimbrough and Harold “Shang-a-Lang” Smith also took Newt under their wings and didn’t just show him where to stand but taught him the hard parts. Complicated changes. How to move through them clean. Shang-a-Lang even wrote out sheet music for Newt so he could read while the rest of the room “was just having a good time,” according to Newt.

Service musicians like Sammy Coleman brought this kind of formal training, big-band charts, and professional expectation into Macon’s local rooms. The Air Force-to-Macon-musician pipeline was powerful: Black service members brought jazz training and steady paychecks into the local scene. The Robins Air Force Base band quietly fed Macon the way a spring feeds a creek — steady, skilled, and often unnoticed until you realize how much it shaped the current.

Sammy Coleman carried that discipline, and Newt absorbed it. Later, Newt would still light up talking about players like Alphonso Thomas and Dr. Ken Timmons — men who could walk onstage and hold the crowd, because the military had already taught them how to hold one together.

Dr. Timmons teaches at Albany State and once played second trumpet for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. He played a Christmas 2025 show at the Douglass theatre and “brought the house down,” according to Newt. Rob Walker, from the Warner Robins’ band Stillwater, played guitar in that show and Newt was there to experience the thrill of a Macon loop coming full circle.

Leroy Wilson, drummer with the Marshall Tucker Band and session player for Capricorn, is a modern-day example of the influence the military band has on Macon.

There were other influences too.

Johnny Jenkins knew Newt’s Aunt Carrie and may have had the greatest influence on Newt. Before Otis broke through, before Southern soul had a name, Jenkins’s raw guitar and leadership taught this young horn player what it meant to show up ready.

Years later, out on the road, Newt watched a guitarist tear up a San Francisco club stage with a sound he describes as thunder — and realized he’d seen the guitarist before, back when he was just another musician drifting through the Macon current, playing with Little Richard’s band and using the name Jimmy James. The guitarist was Jimi Hendrix. In July 1970, Hendrix played the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival in Byron — at a raceway just outside Macon — to the largest American crowd of his career, with Macon’s own Allman Brothers Band heading the bill, where they opened and closed the festival while rising fast on home ground.

Newt says Lewis Hamlin, the lead trumpet player and director for James Brown, was his first mentor.

And all this was before Newt turned sixteen.

After high school, Newt spent a formative year at Morris Brown College, an HBCU in Atlanta, during 1963–64. He practiced constantly, and when members of the college’s marching band heard him, they didn’t ask where he’d trained — they asked him to join. He did. The band awarded him a mathematics scholarship, recognizing what musicians often see before institutions do: precision and an instinct for structure.

At night, Newt played at spots near campus, including the Continental Club, making about thirty dollars a night — real money for a young musician — sometimes alongside Otis Collier (no relation) of the Thunderbirds. In those rooms, Newt often played trombone instead of trumpet, learning how to anchor a section as well as lift it, and showing those college students there’s money in music. Day and night, he moved between worlds that demanded the same thing in different languages: keep time, hit your mark, serve the whole.

That punch and vibrancy is what makes marching bands spectacular and spectacularly entertaining. It sure had an impact on Sam & Dave and Newt’s stage presence in years to come.

Mrs. Gladys Williams: A Macon Icon

Newt’s piano teacher, Green Book hostess, bandleader, and pianist.

Gladys Williams: The Lesson Was the Life

Mrs. Gladys Williams was Newt’s piano teacher, but that word barely scratches the surface. In 1930s Macon, she was a rare thing: a Black woman bandleader with her own orchestra, touring widely through the segregated South, training musicians who would go on to play with local and national acts. Hamp “King Bee” Swain, a WIBB DJ, played in Gladys’ band.

She sang, she arranged, she led. What she didn’t do—by choice—was record.

Newt said she never took her music into a studio because it would have taken too much of her time away from performing and teaching. That detail matters. Gladys Williams wasn’t building a legacy for posterity; she was building people. Her music lived in rooms, on bandstands, and in the hands of the students she trained.

“She worked seven days a week.” Newt says. “She played for churches, funerals, parties at Mercer University, clubs in the region. But Saturdays were for us.” By “us” he means students like him taking private lessons in her home.

Instruction, in Mrs. Williams’ world, was felt in the body, not purely theoretical.

To study with Gladys Williams was to see how a musician survived—and thrived—inside a system designed to hem her in. As a woman in the Jim Crow South, the expectations were relentless: she had to be impeccably groomed, her home kept welcoming and respectable, her reputation spotless. Her house doubled as a safe harbor—part conservatory, part Green Book refuge—where traveling musicians could find good food, rest, and protection from a hostile world.

That’s why names like Sammy Davis Jr., Otis Redding, and Little Richard passed through her door; she had built a house—and a life—that musicians trusted.

Newt recalls Gladys Williams hosting a Sunday Teenage Party at the Bellevue Teen Club. When it outgrew the room, she moved it downtown to the Douglass Theatre. The parties were hosted by people in her music circle, familiar voices from WIBB — DJs who understood that music could also be theater.

Ray “Satellite Papa” Brown made a legendary entrance to the teenage party, descending from the darkened ceiling in a space suit, shooting off sparks from a space weapon, while Hamp “King Bee” Swain worked the microphone as co-host. For the teenagers packed into the theatre, it felt electric — radio voices made flesh, music turned into an event. For Newt, it was Macon not being quiet or modest, but imaginative and proud.

Newt recalls how Gladys walked with a limp, a result of childhood polio. But she was squired around Macon in style by her husband, Herbert, who worked for Huckabee Cadillac. “They always had a new Caddy,” Newt says.

For Newt, the lesson was how to move through music with discipline, generosity, and self-respect. How to host. How to listen. How to make room for others without shrinking yourself.

“She was tough. Even if you did it right she’d say ‘Do it again.’ She taught me to memorize everything I played.”

That way, Newt could keep playing even if his sheet music fell to the floor.

But the men molded him too, especially Clint Brantley.

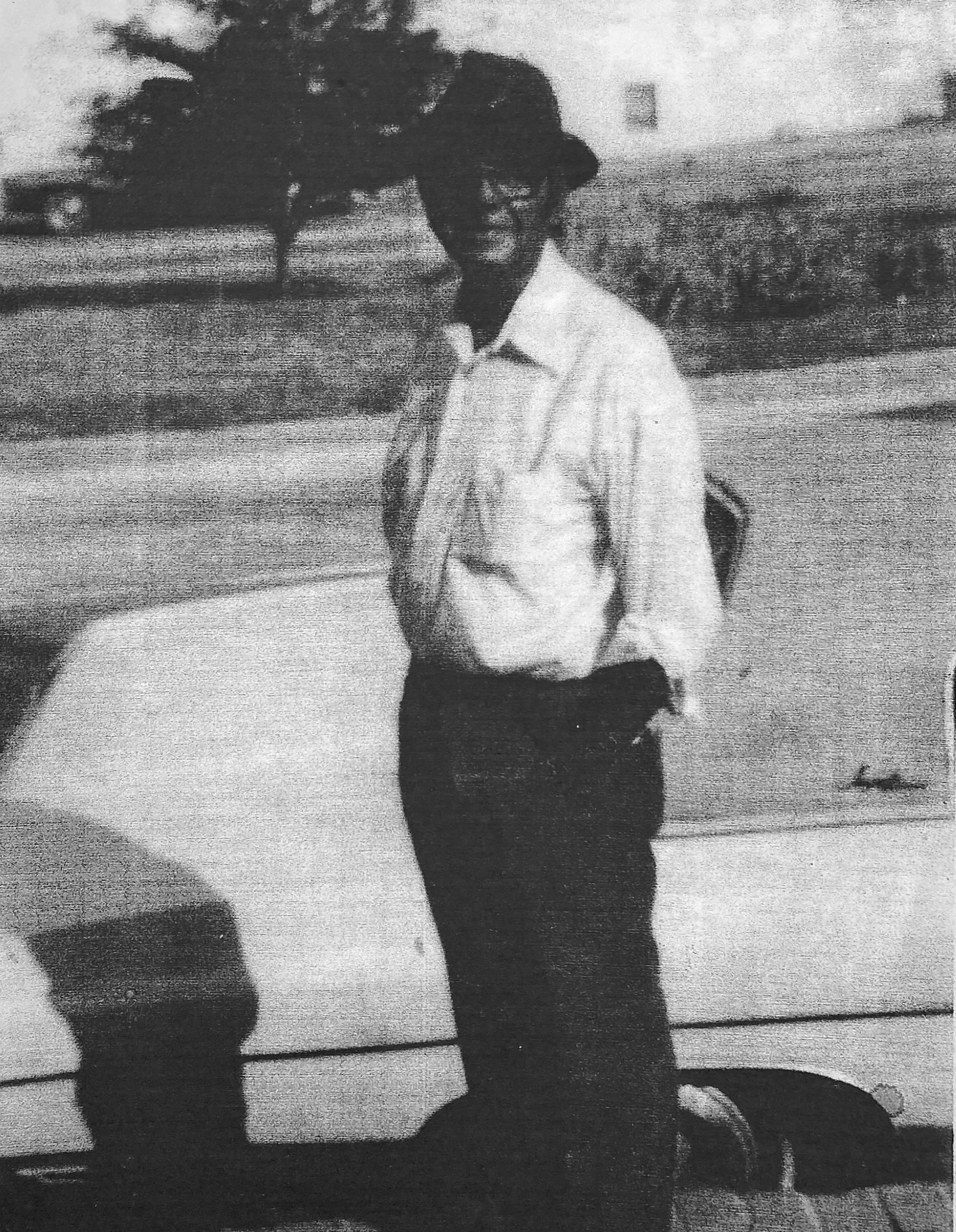

Clint Brantley in Macon, photographed during the years when his clubs, bookings, musician training, and instincts helped shape the city’s Black music economy.

Clint Brantley: Architect of the Scene

Clint Brantley Sr. began shaping the working architecture of Black music in Macon in the 1930s. Through clubs like the Two Spot, The Key Club near Walnut and Fifth Street, and later Club 15, Brantley functioned as more than a venue owner — he was a booking agent, concert promoter, talent broker, and informal educator, assembling bands, rotating young players, and training them to back touring artists moving through the Chitlin’ Circuit.

Newt remembers the Key Club as a small room with outsized traffic — a place where bands got tried out before they were sent down the road.

Contemporary accounts and later retrospectives place the Two Spot among the most active Black-owned venues in the region, a place doing steady business well into the 1960s and 70s. Long before Macon’s soul and R&B scene gained national attention, Brantley’s clubs operated as proving grounds, where musicians learned not only songs but the rhythms of professional life: when to step forward, when to fall back, and how to hold a stage under pressure.

The Two Spot was not a glamorous room, but it was a working one, operating as an anchor on Macon’s Chitlin’ Circuit—a place where touring acts could count on a crowd and local musicians could count on stage time.

Under Brantley’s watch, young players like Newt learned by doing: rotating in and out of bands, backing singers they’d never rehearsed with, picking up arrangements on the fly. The emphasis was reliability, but polish mattered too. If you could hold the groove and follow the singer, you got to work.

Brantley’s reach extended well beyond Macon. He nurtured the early careers of artists like Little Richard and James Brown by managing, booking, or steadying their careers at crucial moments. In the mid-1950s, when Little Richard left Macon with touring dates still on the books, Brantley filled them with a then-unknown James Brown, keeping the circuit alive while a new star was quietly being born.

“Back then, before TV, folks in rural towns didn’t know what Little Richard even looked like,” Newt says with a chuckle. “So Clint sent James Brown out in Little Richard’s place, without telling them it wasn’t Little Richard.”

Brantley didn’t work alone. He surrounded himself with men who could move music from room to room and city to city. One of them was Macon native Henry Nash, who got his start working for Clint before going on to become a booking agent at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. It was Henry — who affectionately called Newt “Birdsong,” after his mother’s maiden name — who later booked Sam & Dave into the Apollo, closing a circle that began in Macon and ended under Harlem lights.

Another Maconite was Richard “Dick” Scott, who handled advertising and booking for Little Richard during the years when Brantley was helping steady his career. Dick would go on to work with Berry Gordy at Motown, guiding the Primettes before they became the Supremes, and later navigating the pop machine of New Kids on the Block — the same Macon-born pathways fed both soul and the wider American music business.

Music was a business for Brantley, but Newt says he was driven as much by love as by money — a hustler with a true believer’s heart.

Brantley was also known to be a cousin of Berry Gordy Jr., the founder of Motown Records, whose family came from Sandersville, Georgia, before joining the Great Migration north to Detroit. Newt points out that the Gordy story, like so many Southern stories, carries both Black and white bloodlines: Gordy’s family descended in part from James Thomas Gordy, a white Georgia slaveholder who had a child, Berry Gordy, with an enslaved woman named Esther Johnson — a history that still ripples forward, even linking the Gordys distantly to Jimmy Carter through Carter’s mother, Bessie Lillian Gordy.

Each year, when Berry and the Motown Revue came through Macon, Newt tagged along to picnics at the Gordy family property east of Macon in Sandersville — running loose among singers who would soon shape American music, absorbing it all as something natural and near, not distant or legendary. Those picnics are some of his favorite childhood memories.

The group of Motown artists included Georgia-born performers like Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops, who hailed from nearby Sparta, where Newt’s own maternal line was rooted. Motown’s brightest lights still carried Southern soil on their shoes.

Newt recalls the Motown Revue bus parking downtown near the Douglass Theatre and all the performers disembarking to walk the streets, shopping and sightseeing. When their gigs in Macon were done, The Motown Revue would load back onto their bus and head to Augusta or Athens to perform.

For young musicians like Newt, hanging around Brantley’s clubs and picnicking with Motown artists was about proximity to talent they could learn from; watching bands form and dissolve, seeing how singers were backed, and absorbing the unspoken rules of the room. For example, Newt would eventually play with Otis Redding a few times, including a show in Atlanta in 1963, with Sammy Coleman also onstage.

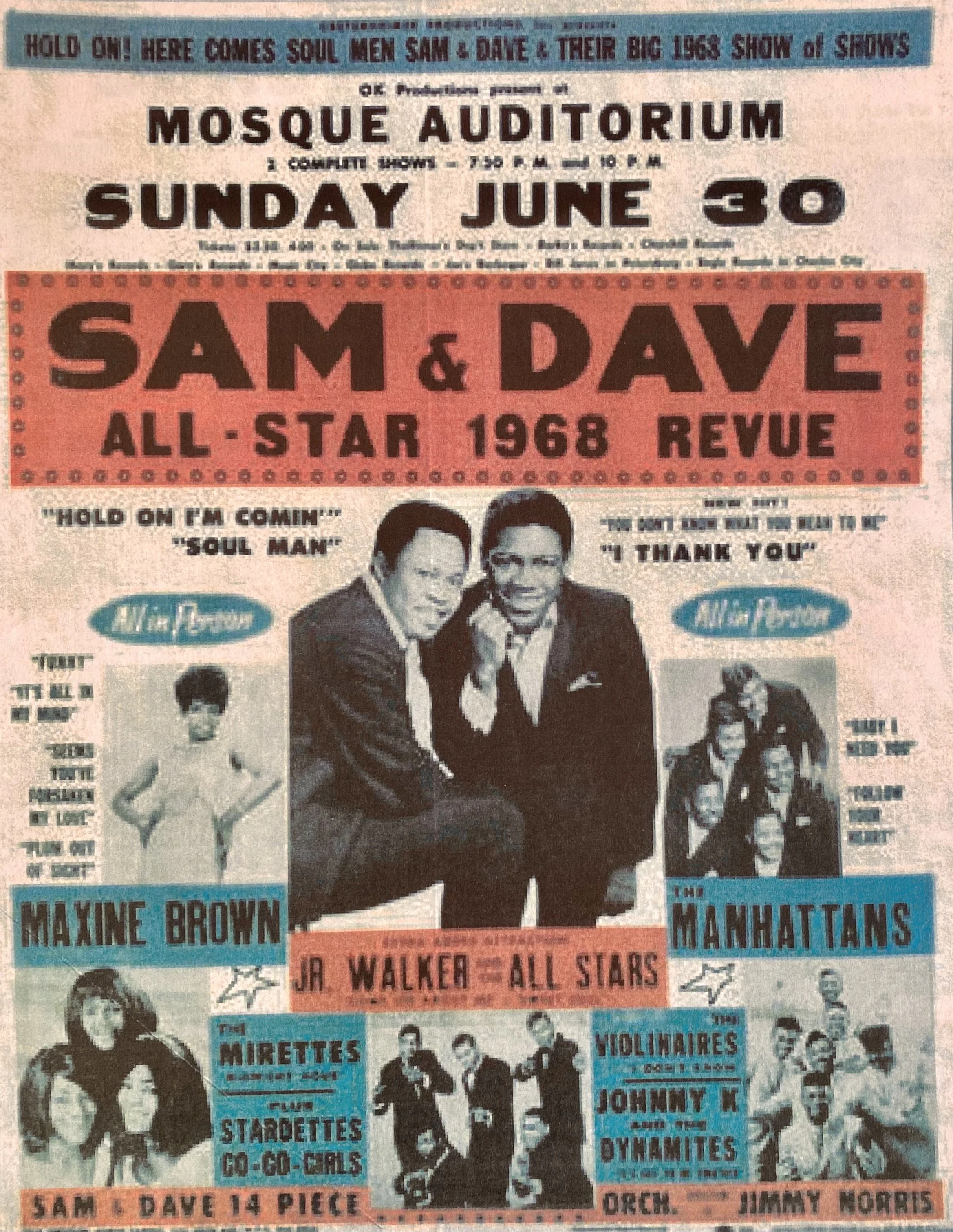

Soul Men Sam & Dave and their Big 1968 Show of Shows.

The Big Stage Comes Calling

By the time he was a teenager, Newt was in demand, playing the piano, trumpet, and trombone around Middle Georgia. He learned fast and listened hard, already working the circuit — sitting in with Johnny Jenkins, the Eldorados, the Flatstone Group, and the Bossa Nova Band at places like Club 15 (on Gray Highway that opened at 12:01am after other nightclubs closed at Midnight), Adams Lounge in Butler, GA, the Elks Lodge, and the VFW.

Some of the rooms where Newt learned his way around music sat in what older Macon residents called the Little Tybee district, near Bay and Seventh Streets. The name reached back to early settlers from the coast, and the buildings still carried that lineage—dark wood, steep roofs, small and close to the ground. By the time Newt came through, nightclubs were known simply as juke joints. Places like the Coconut Grove weren’t polished, but they were alive.

Newt’s gift in all venues was blending — listening first, then fitting himself into whatever sound the room needed. And he never lost that marching-band discipline. It didn’t stay on the field — it traveled with him.

Sam Moore and Dave Prater were deeply influenced by the sound and spectacle of marching bands, especially those at HBCUs, where precision met joy and the horns drove the song forward.

When Sam & Dave built their band, they hired accordingly. Carl Vickers came straight from Florida A&M’s marching band his senior year. Five players in total had roots at FAMU. The second horn player to join the group, Cannonball (Nat) Adderley, was also the band’s director — another product of that tradition. What audiences felt as explosive soul was, underneath, carefully trained marching muscle memory: tight horn stabs, choreographed movement, breath controlled under pressure.

And it wasn’t just precision — it was comedy. Sam & Dave were hilarious, and Newt was too, on and off the stage.

The whole band moved, joked, and played at the same time, horns dancing along with the singers. With as many as fifteen players onstage, the show could feel like a parade.

“They called it showboating,” Newt once said about his own performance style—pushing into a high register, driving the horn hard, matching the physical intensity of the other performers. They played so hard they to had to soak their feet in ice after performing, and rub campho-phenique on their lips.

But before joining Sam & Dave, Newt made a detour to Augusta, Georgia.

The Swinging Dukes and the Doorway Out

The Swinging Dukes — a professional, sharp-dressed, horn-heavy R&B band connected to musicians like Maceo Parker, Melvin Parker, Leroy Lloyd, and H.L. Berry — offered Newt an opening. He took it.

That choice, he says, “changed everything.”

The Dukes were another training ground: rehearsals tight, choreography precise, horn stabs exact.

One night, while Newt was playing with the Air Force band at the National Guard Armory, the Dukes heard him. Within months, he was touring with them.

And THEN came Sam & Dave.

At seventeen, Newt stepped onto the road behind the most electrifying soul duo in America.

Dave Prater was born in Ocilla, Georgia, though Newt always said Dave considered himself truly formed in Sankamo, Georgia, before growing up in Miami.

Sam & Dave themselves came together almost by accident. Sam was emceeing a show — singing, joking, working the crowd — when Dave stepped up to sing. As Sam turned the stage over to him, his foot tangled in the microphone cord. What might have been an awkward moment turned into unintentional slapstick, and the crowd loved it.

The chemistry was immediate. What started as a stumble became a partnership built on timing and knowing how to recover mid-step — a skill every great performer learns, and every great band needs. Eventually that trust would erode, paths would diverge, and cross again years later, more cautiously but also more compassionately. Time does that to people and wounds.

In those early days of Sam & Dave, the gigs were glamorous onstage and sometimes dangerous offstage in the South. Segregation shaped every mile: bands slept in safe houses, trusted certain kitchens, avoided certain counties after dark. Families fed them, tucked them into makeshift beds, sent them back on the road with plates of food wrapped in foil.

For a Black teenager in mid-century Georgia, the road was more than asphalt and signs — it was coded terrain. The Green Book became the silent compass in every glove compartment. The Douglass Hotel. Mabell’s Place. Jean’s Restaurant. Richmond Hotel.

Some nights the only safe place to sleep was someone’s sofa in a house where the parents treated you like their own — feeding you, praying over you, sending you off with sandwiches in wax paper.

These safe houses formed a network of protection that made the music possible at all.

College gigs found them playing mostly for fraternities against the backdrop of race riots, or escorted to the stage by state troopers. The applause didn’t erase the fear, but it carried them through it.

“Those were stressful times,” Newt has said. “The Chitlin’ Circuit was our relief during segregation and allowed us to let our hearts out.”

Travel, then, was not just movement. It was calculation. It was choosing the right roads, the right doors, the right tone of voice.

Newt recalls band members splitting up and going to different homes after gigs, where he’d stay in rooms with other kids and enjoy breakfast with the host family.

“It was like staying with cousins,” Newt says, “and family. Especially if there was a mother and father in the house.”

Somewhere between borrowed bedrooms and breakfast tables, between fear and fellowship, Newt was approaching a stage far bigger than any Georgia town — a place where all that road-learned rhythm would meet its echo: the Apollo.

Live At the Apollo Theater

In the narrow hallway backstage, the air is tight and hot. Bells buzz. A stagehand points, then points again—stand by. Newt adjusts his grip on the trumpet, the metal warm already, valve springs answering his fingers with familiar resistance. He’s learned to read rooms by sound. This one is murmuring before a note is played.

The band steps out behind Sam & Dave, and the reaction hits instantly—shouts, whistles, someone laughing hard like they just saw an old friend walk in. Sam doesn’t waste time easing them in.

The opening notes of “Soul Man” land like a match struck in dry air.

People are on their feet now, clapping overhead, shouting the lines back before they’re finished being sung. This song of gospel fire is theirs; Black pride declared without apology, call-and-response turned into a collective vow.

Newt raises the trumpet and locks in, that marching-band precision adding to the awe.

Here, the horn doesn’t decorate the song—it drives it. Short, bright stabs push the vocals forward, answer the shouts, keep the whole thing airborne. The rhythm section hits hard, gospel muscle memory turned loose in a room that knows exactly what to do with it.

Sam shouts. Dave answers.

Someone near the front leans forward, shouting “Yeah!” at exactly the right moment. This is what people mean when they say the Apollo is alive. The audience doesn’t sit across from the stage—it meets it halfway.

Newt can’t see the audience, the lights are too bright, but he feels the feedback loop close. The sound comes to him thick and warm, bouncing off the walls, feeding the band’s energy right back at them.

This is why Black performers talk about the Apollo the way they do. Not because it’s cruel, but because it’s truthful. If you bring it, the room carries you. If you don’t, it leaves you standing alone.

When “Soul Man” hits its final turn, shouts and bodies keep moving even as the band cuts clean.

Backstage, the heat lingers. Someone laughs hard, relieved. A hand slaps Newt on the back as he lowers the horn—quick, grateful, already moving on.

That’s the other truth of nights like this: the spotlight doesn’t stay on the band behind the stars. The crowd knows the song. The singers take the bows. The music keeps moving.

Newt wipes the mouthpiece on his sleeve and sets the trumpet down, the sound still ringing in his ears. He was part of it—part of the lift, the drive, the moment when a Southern soul song filled a Harlem theater and came back louder.

He doesn’t need his name called.

The room already answered him.

Onstage, Sam & Dave were the same fire every night. But the rooms weren’t. The whole band learned to read each room and knew how to send that particular audience to the moon and back.

Carla Thomas onstage with Sam & Dave, with Newton “Newt” Collier centered behind them—part of the working band that carried Stax’s sound from studio to stage.

The Ed Sullivan Show

This room is quiet. Not empty—just controlled.

Everything has its place. Tape marks on the floor. Camera tracks laid like rails. Lights aimed, measured, unforgiving. Even the air feels different here, cooler somehow, scrubbed of sweat and noise before it’s allowed inside.

Newt looks down at the white tape outlining where his shoes are supposed to land. Don’t drift. Don’t step forward. Don’t turn too far. The instructions come softly but firmly through headsets and hand signals. A stage manager lifts two fingers. Two minutes.

This isn’t the Apollo. Newt doesn’t expect answering shouts or bodies rising as one. This room doesn’t answer back so overtly—it records.

Across the stage, Sam & Dave are already in position, microphones adjusted to exact height. The band stands behind them, spaced wider than usual so the cameras can see everyone at once. Newt shifts the trumpet slightly.

A voice counts down.

Ten. Nine. Eight.

Somewhere beyond the lights, Ed Sullivan waits with his cue cards. Newt knows the significance of this stage—every musician does. The same floor where Elvis Presley stood, where The Beatles shook the country awake. Tonight, a Black Southern soul song will step into millions of living rooms that didn’t ask for it.

Three. Two.

The red light snaps on.

The opening notes of “I Thank You,” lands clean and bright, just as rehearsed. The band locks in immediately—no room for adjustment now. Newt plays exactly what the song requires, no more, no less. Short horn blasts, precise and joyful, placed so they lift the vocals without pulling focus.

The room reacts and begins to move, but no roar. No laughter yet. Just the hum of cameras and the faint shuffle of crew moving silently behind them. The studio audience sits forward with the TV audience somewhere else—scattered across the country, watching from couches and kitchen chairs, some leaning in, too, while others fold their arms.

Newt feels the weight of it.

This performance isn’t being offered to one room—it’s being sent. Beamed into places where soul music is still called noise, where Black joy is greeted with suspicion, where the word soul itself unsettles. It’s 1969 in America and he plays anyway. That’s the job. That’s always been the job.

Sam and Dave hit the call-and-response, their voices carrying the heat. The song holds. The groove survives the translation through television wires.

Newt keeps his eyes forward. He doesn’t look for reaction. He trusts the arrangement and the hours spent in rooms like Stax where sound learned how to travel intact.

The final note floats under the lights. Clean cut. Applause rings back—a controlled but awed wave of claps, only fading after the cameras swing away.

The red light goes dark.

Someone exhales. A stage manager nods. Good.

Newt lowers the trumpet and steps back from his mark. In a few seconds, the set will be struck, the floor cleared for the next act. Out there, though, something else is happening. A Southern Black song is still moving through wires and into living rooms, settling where it will.

He doesn’t know who will hear it as invitation and who will hear it as challenge. He only knows this: the music made it past those front doors.

And he was part of the reason it did.

Watch: A 1966 episode of The Beat!!!, hosted by Otis Redding, featuring Sam & Dave’s band—with Newt clearly visible—alongside performances by Percy Sledge, Patti LaBelle and others. Fast, joyful, and very much of its moment.

The Glory and the Grind

Nights blurred into years. The Fillmore West. The Apollo. The Merv Griffin Show. The Ed Sullivan Show three times. TV lights and long highways, grief and ecstasy inside the same horn.

Stax Records in Memphis became another home — where Wayne Jackson, Steve Cropper (“the lick man”), Booker T. & the MGs, Carla Thomas, and Otis Redding’s crew shaped the sound of soul in real time. Newt didn’t just witness it. He played inside it and beside it onstage. He recorded at Muscle Shoals with Arthur Conley and Arthur Alexander. He watched Percy Sledge bend a note so deep the studio floor seemed to warp.

Those were the golden years — the glory and the grind. Those were the years when his horn paid the rent.

By the early ’70s, as Sam & Dave’s partnership frayed and the road grew harder, Newt stepped away from the duo and eventually settled in Boston, working as a house musician and taking touring R&B dates when they came.

After a show at The Sugar Shack in Boston in 1976, on his way home, Newt was shot in the face by an unknown assailant. The injury shattered his jaw and changed the physics of playing brass. Recovery took years, multiple surgeries, and forced a reinvention that most people never survive, much less make art out of.

While healing, he learned electronics at MIT, worked at Wells Fargo and Honeywell, and studied at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. Eventually, Newt found his way to the E.V.I. — the Electronic Valve Instrument — a horn that required less air and opened a path back to music, on gentler terms. A fellow Boston-area trumpeter, Mike Metheny, helped guide him there — a friend who understood both the physics of brass and the grief of nearly losing it. (Mike’s brother, Pat Metheny, would go on to become one of jazz’s most celebrated guitarists, but in those years he was simply part of the same listening circle.)

It was this long, stubborn return to sound that later caught the attention of filmmaker Win Scott, who met Newt while working on another project in Macon and realized he was standing in front of a story that wouldn’t let him go. The result was NEWT: A Short Documentary produced by Moira Glennon and released at the 2025 Macon Film Festival — a portrait of a musician who refused to stop making music.

Newt doesn’t traffic in tragedy, though. He calls hard things what they are, then keeps moving. When the music came back, so did he — slower, maybe, but sweeter. There’s patience in his phrasing now, tenderness in the way he holds a horn, as if he’s thanking it for waiting on him.

The Record Store Years

By the late 1980s, Newt returned to Macon to care for his ailing Aunt Carrie. Settled back at home, he opened Collier’s Corner, a record shop on Napier Avenue during the era when record stores were Macon’s unofficial conservatories. Newt’s shop was filled with his personal vinyl collection, focused on jazz, R&B and Soul, and the walls sported gig posters and photos.

Newt’s shop joined Zelma Redding’s store and others like Record Bar, Steamboat Annie’s, and Camelot Music in carrying forward the city’s musical history after Capricorn closed.

Those shops were where the knowledge lived on: what to listen to, who played what, who came through town, what the elders remembered.

When Newt’s store closed in 1997, after 10 years in business, he drove a Radio Cab for years in Macon, gave impromptu musical tours for passengers, gathered more stories, and kept mentoring young musicians.

So when people talk about Macon’s music scene, they often point to clubs, promoters, and stars—and rightly so. But beneath that visible structure is a quieter framework, built by women like Gladys Williams and Zelma Redding, who taught by example what it meant to live a music-rich life under pressure. And people like Clint Brantley, who provided the stage, and people like Newt, who keep bringing it all forward and putting it in our hands to marvel over.

The Father Mystery

Newt rarely discussed his father, Newton Collier Sr, growing up. The family just didn’t bring him up in conversation. Newt Sr’s absence was simply folded into the rhythm of life. But decades later, after his father’s death, Newt found clues that suggested his father’s life had been fuller — and more musically connected — than he ever knew.

His father once worked in the restaurant at the Dempsey Hotel, now the apartment building where Newt lives. When Newt traveled to Orlando for his father’s funeral, he found posters tucked away — posters of the Silas Green Show from New Orleans, a touring Black tent-show revue that shaped early jazz and vaudeville culture.

Newt was handed phone logs too, documenting long conversations his father had with women who seemed to be former members of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, the legendary all-female jazz band that toured military bases and Black communities before and during WWII.

One night in Barnesville, Georgia, Newt walked into a small club and heard a group of old men murmur, “That’s Newton’s boy.” They knew his father, who was from Barnesville. Some called Newt Sr. a “promoter.” Some said “front man.” Others said “musician.”

Newt leans toward his father being a front man, or advance man, the guy who would travel ahead of the entertainers to procure lodging and ensure the venue was set up properly. Newt has done some of that in his day. He doesn’t know for certain which entertainers his father was fronting, but he leans toward the Silas Green Show and even the International Sweethearts of Rhythm.

Newt learned his father always wore alligator boots, and Newt has always worn an alligator belt.

While in Orlando for his father’s funeral, his dad’s girlfriend, Betty, instructed Newt to visit the nearby Native American reservation. When he arrived at the entrance and gave his name, and why he was there, they immediately called for a Miss Willie to come out. When she heard the news of Newt Sr’s death, she was rattled, as though they were close, or even kin.

“We’re supposed to have some Native American in our line,” Newt says.

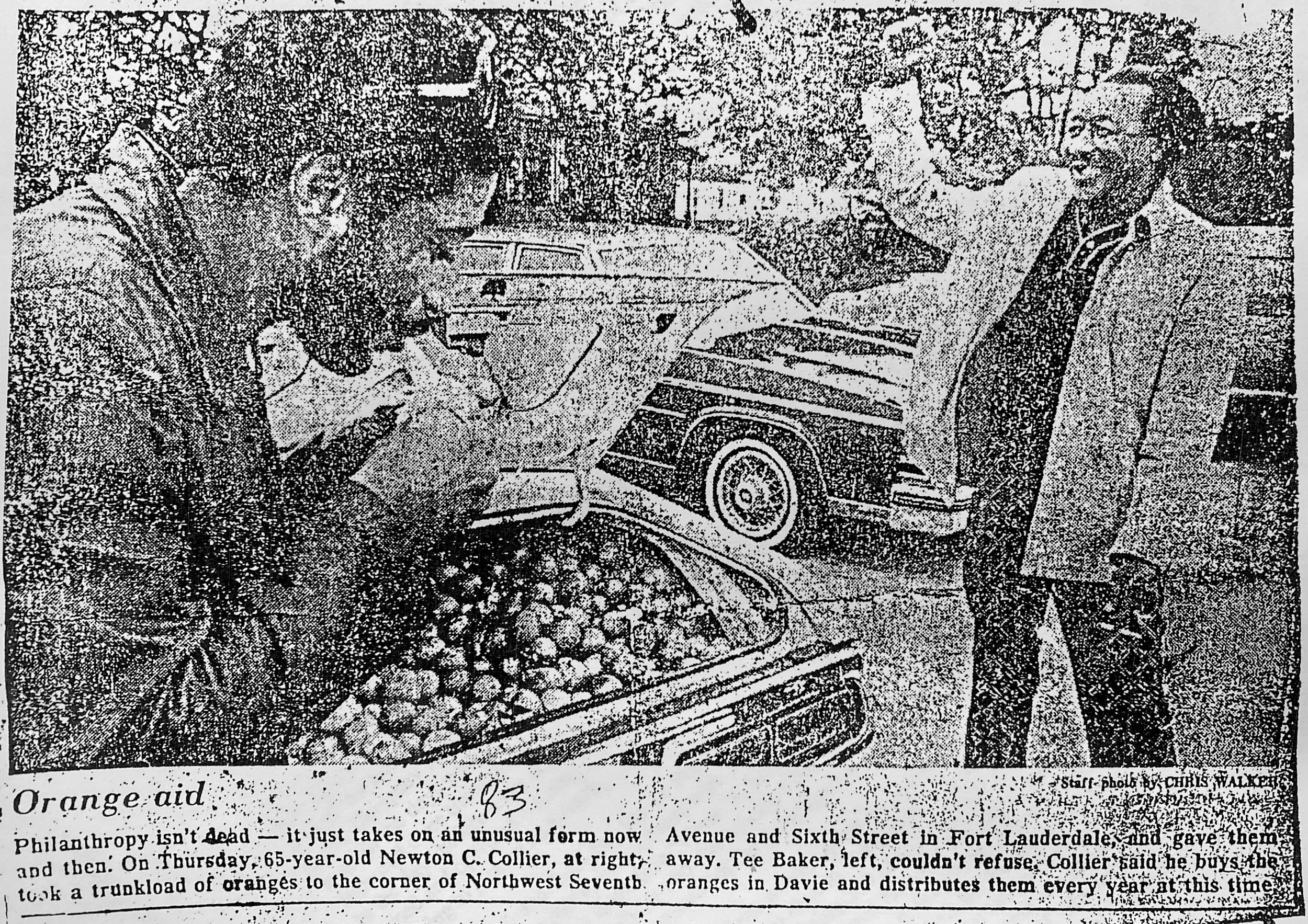

Newt’s father was also known for buying and giving away oranges from the trunk of his car, a public act of generosity.

A photograph of Newton Collier’s father, Newt Sr., featured in a local Florida newspaper for distributing oranges to strangers—one of the few surviving images Newt has of his father.

Each new piece of information Newt finds deepens the mystery, not always the clarity. Is Newt related to Charles Collier, who started the Silas Green show, as he’s heard? Was Newt really cousin to Charles H. Douglass of the Douglass Theatre family, since Newt and Richard Douglass called each other “Cuz” growing up?

These are truths to Newt on one level, because he was told the stories, yet he also holds questions about these fragments of oral history, passed to him in a world where Black lineage was often remembered in voices rather than ledgers, and much of it erased or not kept at all.

These many pieces explain something, whether they’re documented fact or rich family lore: Newt had inherited not just an ear for sound, or the promotional skills, but a heart full of generosity and community-building. And resilience.

He speaks of his father gently, without resentment — more like a man who finally understands the shape of the shadow he’s been walking beside his whole life.

Daughter Charity

Newt speaks about his daughter, Charity Collier, with a particular softness, even when he insists they aren’t especially close. But the evidence of closeness is there if you listen the way musicians do—not for volume, but for return. He mentions her often. They text. They share photos. He notices what makes her light up.

Newt shared a video of Charity from a recent book launch party—her own novel, Making it Over the Tobin Bridge, released into the world with joy and people celebrating. In the video, Charity is radiant, grounded, at ease in her body and her purpose. She has worked hard for that ease by training in meditation, yoga, and grief-support practices, and also offering what’s she’s experienced to others; giving people a way back into their own bodies and breath — to keep going after loss.

Charity’s professional life is devoted to systems advocacy and mental health—work that rarely seeks the spotlight but quietly changes outcomes for real people. She helps navigate the intersections of trauma, justice, and care, guiding people toward the resources that can steady a life when it has come undone.

Newt laughs when he tells me about a pair of shoes. Charity had sent him a photo, and she was wearing the exact same pair he’d recently bought for himself. Aesthetic alignment between them, yes—but also something deeper: the quiet mirroring that happens between people who move through the world with similar attention. Both are readers. Both are reflective. Both are givers to their communities. Both search for language—spoken or written—that can explain experience without dampening it.

Charity, born to Newt and his wife Beverly Jean Nelson in 1973, grew up in Boston with her mother after the marriage ended. Newt carries that distance quietly, not as a grievance, but as something tender he remains mindful of. Still, when it mattered, Charity was there on June 8, 2019, standing on the sidewalk outside the Douglass Theatre as his name was set into the Walk of Fame, witnessing her father being honored not just for the notes he once played, but for who he is to Macon now. Presence, after all, is its own kind of closeness.

Charity isn’t a reflection of Newt, but a continuation. They both want to improve this world. Their song doesn’t repeat. It evolves through love, space, and the hard work of healing for themselves and others.

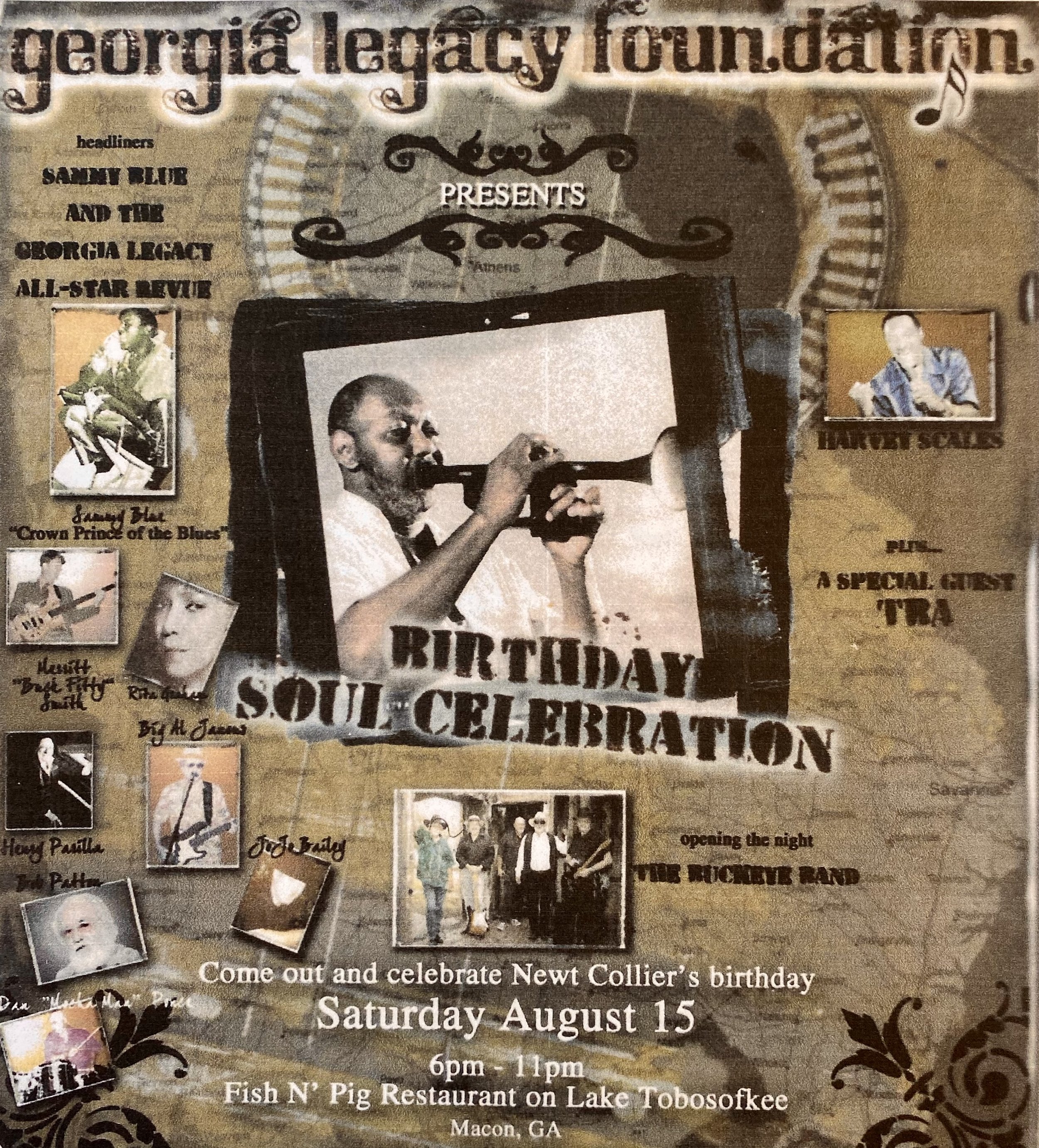

The Georgia Legacy Foundation

Newt has always been doing the work. He served seven years as president of the Georgia Legacy Foundation, helping build a lifeline for elder blues musicians who had given their sound to the South and were now moving into retirement. The Foundation functioned the way Newt believes music communities should: practical and relational. Artists like Princess Riley, Frankie Robinson, and Eddie Teegna weren’t treated as throwbacks; they were booked, supported, and made visible again.

The Foundation partnered with the city of Barnesville on the annual BBQ & Blues Festival, an event that began with a few hundred people and grew into a gathering of thousands.

Barnesville wasn’t just a venue—it was personal to Newt. His father’s family came from there, and the festival was held across the street from the home of a prominent white Collier family, a reminder of how long—and how unevenly—names and histories have traveled in the South. Newt’s family has long believed these two Collier families are connected, whether or not the paper trail ever proves it. He also traces family connections from Barnesville to Dr. Henry Collier of Savannah, another linkage that keeps surfacing wherever history, education, and Black advancement intersect.

The BBQ & Blues festival brought people together in a place once shaped by separation, and Newt was handed a Key to the City of Barnesville. Like COMP today, the Georgia Legacy Foundation was about care. About making sure the people who nurtured the sound for decades and brought us great pleasure aren’t left alone.

The Legacy in Real Time

You don’t have to look far to find Newt in Macon — chances are, he’ll find you first. He might be sitting at the Vice Bar on a Saturday evening, nodding in time with a young horn player’s solo. Or maybe he’s at Grant’s Lounge, where he once played, leaning against the wall, listening with the same alert joy that has carried him through every reinvention.

He still plays a little — two or three times a year — just enough to feel the familiar lift in his chest. What he loves more now is watching others find their sound, and putting down a solid record of all he can remember. Newt is still making lists — clubs, streets, names, dates — as a way of keeping his memory map intact, and of preserving the stories of his fellow sidemen too. Many are no longer here to tell their own.

This winter, the door to Newt’s musical generation creaked a little further closed when Sam Moore — his former bandleader, his old road boss, his friend — passed away at age 89 on January 10, 2026. When the news reached him, Newt sent a simple message that carried decades of music inside it: “He was one of the best.” And Sam was.

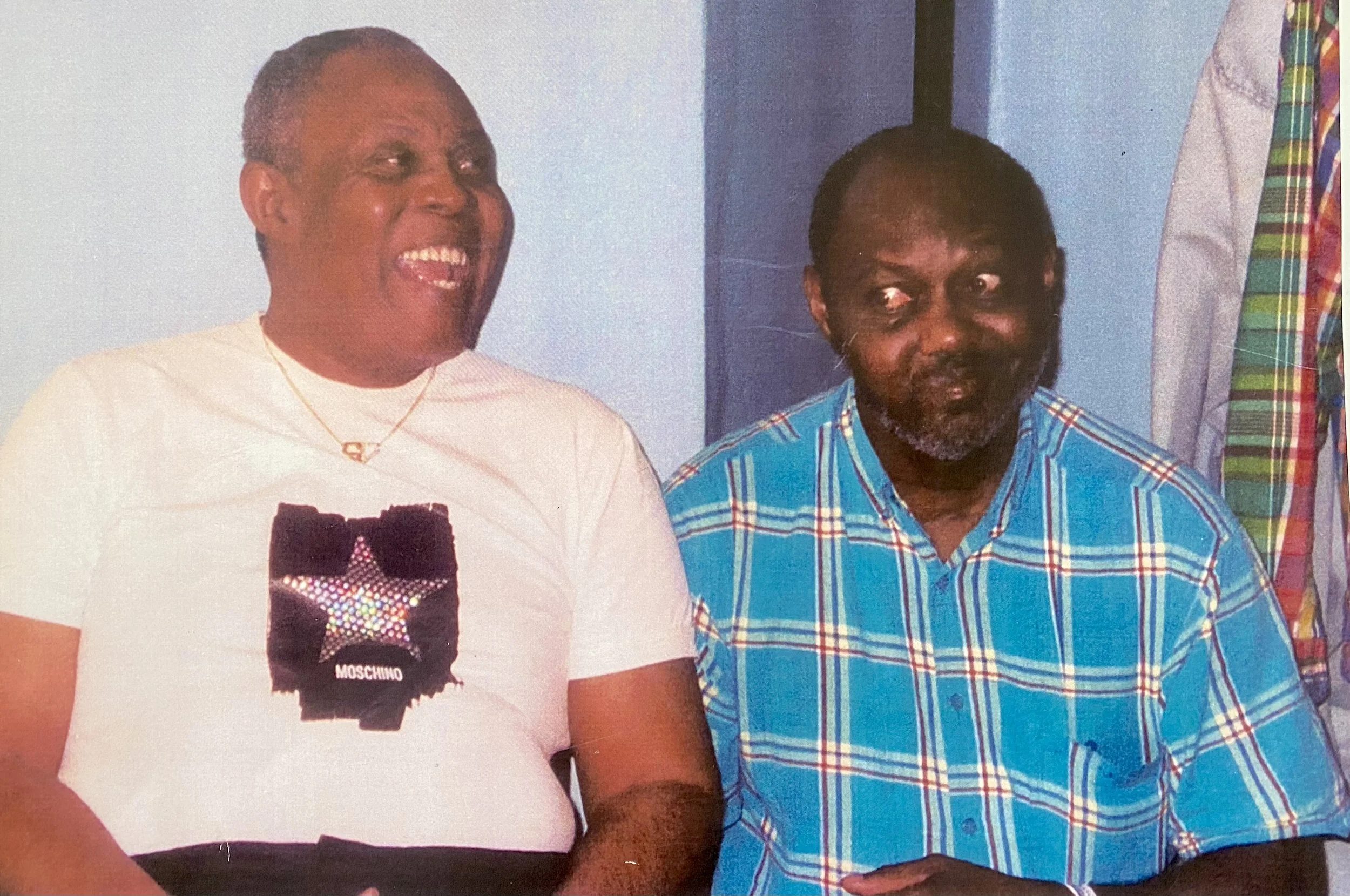

Newt with Sam Moore, longtime friend and bandmate, still laughing years later.

But the loss of Sam was just one in a spate of departures that have reminded Newt and a whole musical community of its fragility.

Just weeks earlier, Steve Cropper, the soul-shaping heartbeat of Booker T. & the M.G.’s and co-writer of timeless songs like “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” died at 84, leaving behind an influence so woven into American music that entire genres carry his fingerprints.

And on January 10, the same day Sam Moore died, Bob Weir, co-founder of the Grateful Dead and a towering figure in the jam band world, died at 78 after a brave battle with cancer. His passing marked the end of an era that traced threads from 1960s counterculture to communities still gathering in song today.

These were not distant icons to Newt, but part of the same living ecosystem — the same circuits, stages, and conversations that once felt endless to him. Over decades of touring, recording, and backing major acts, Newt crossed paths with these artists and others who shaped the twentieth century.

Most recently, in mid-January, word traveled that Earl "Speedo" Simms had passed. Speedo sang with The Singing Demons and worked with many R&B artists, but was best known as Otis Redding’s tour manager — a steady presence behind a brilliant machine. He was supposed to be on Otis’s fatal flight but gave up his seat at the last minute. When Willie Perkins stepped into his role as tour manager for the Allman Brothers Band in 1970, Speedo went with him to oversee his first show and teach him the ropes. These days, Willie and Newt mourn the loss of Speedo while lunching together each month at the COMP gathering.

What these recent losses underscore isn’t merely the passing of remarkable performers — it’s how few remain who inhabited that world when it was still alive and shaking. Newt is among those few who remembers that era not as history, but as lived time: the sound of Sam’s voice in a room, the feel of Steve’s guitar leaning into a groove, the improvisational sweep of Bob’s rhythm carrying a room through sunrise. Their music didn’t just echo — it grew roots in the hearts and bodies of everyone who heard it live.

We live in a moment unlike any before it. We can watch the past move and speak and sing — in photographs, film, and recordings that let us witness a whole life from youth to old age. But that only makes the ache sharper when the people who made that world begin to leave it. What remains, then, are the ones still here, like Newt, carrying memories of how it felt, how it sounded, how it unfolded when no one yet knew what it all would mean.

Newt never set out to make history. Like most of us, he stumbled into his life — following his love of music, taking lessons, hanging at the Two Spot, gig by gig, city by city — learning as he went, guided more by curiosity and chance than by any grand plan. Only now, looking back across the long arc of it, does the shape become visible: Newt’s life spent inside music as it was being born, evolving, colliding with the world.

Newt understands how fragile that gift is — how easily time can take rhythm and memory away. That’s why he keeps showing up: at lunches, at shows, in conversations, breathing life into a city that taught him to dream in syncopation, and adding those precious papers to his own growing archive at the library.

Newt has also quietly collected traces of Macon musicians whose stories risk slipping through the cracks—printouts, clippings, handwritten notes, names worth remembering. Some went on to national recognition; others returned home after the road or life wore thin. What links them is not fame but fact: they played, they worked, they contributed. Many passed through the same tight circle around Otis Redding, Johnny Jenkins’ Pine Toppers, and Phil Walden’s early orbit—proof of how small and interconnected Macon’s music world really was.

Newt doesn’t present himself as an archivist. He simply keeps the record close. For instance, in one folder are notes on musicians like Thomas Bailey, who fronted the Flintstones in the 1970s; and reminders of figures such as Henry Nash, who managed Sam Cooke, B.B. King, the Commodores and others, or Ishmael Mosely, who went from a Macon childhood into touring work after Otis personally asked him to join the band. The throughline for Newt is less about celebrity and more about connection and continuation.

For posterity’s sake, Newt keeps these notes in folders and in posts on Facebook, about the people he knew and played with and learned from, the folks who shaped our world through melody and backbeat. And who are now gone.

As long as Newt is here — listening, remembering, telling — that great era hasn’t vanished. It’s still playing, softly but steadily, through him.

Coda: The Song Still Rising

There’s something holy about the way Newt carries himself — like a man who’s made peace with every note life ever gave him, even the broken ones. He doesn’t need to rehearse his story anymore; he wears it like a suit. Or a comfortable ball cap.

Wherever I see him, which is often, I’m always struck by how present he is — not stuck in what was, but rooted in what still matters. When he talks about the music, he’s channeling motion not just memory.

He was only seventeen when Sam & Dave pulled him onto the road, a boy with a trumpet and trombone, and a world about to open. A world he would travel around five times! The years that followed — the fame, the bullet, the silence, the slow rebuilding — could have hardened a lesser soul. But Newt turned it all into breath again. Into sound. Into gratitude.

Newt has crossed paths with nearly everyone who passed through Macon’s musical bloodstream. Over a lifetime of playing, touring, and listening, Newt has seen and heard more stories than most—some funny, some hard, some best left where they belong. He once described himself as a “keeper of secrets,” not out of mystery or mischief, but out of respect for the music and the people who made it. He knows the private costs that often travel alongside public art, so what he chooses to carry quietly, he offsets by what he gives freely: memory, context, and sound.